The University of Vermont’s Institute of Agroecology (IfA) is excited to announce the recipients of a new, small grant program: Community-Engaged Research in Agroecology and Food Systems. With funding from the Office of the Vice President for Research, these grants will support a cohort of UVM faculty undertaking community-engaged research projects related to agroecology and sustainable food systems.

“These projects bring UVM faculty and students together from different colleges across campus with community partners in meaningful and impactful action research projects,” Colin Anderson, the IfA’s Associate Director, said. “We are excited to engage with all project partners in this year-long learning cohort. By meeting together throughout the year to share experiences and to learn together, we will deepen our understanding of agroecology and our practice of community-engaged participatory research.”

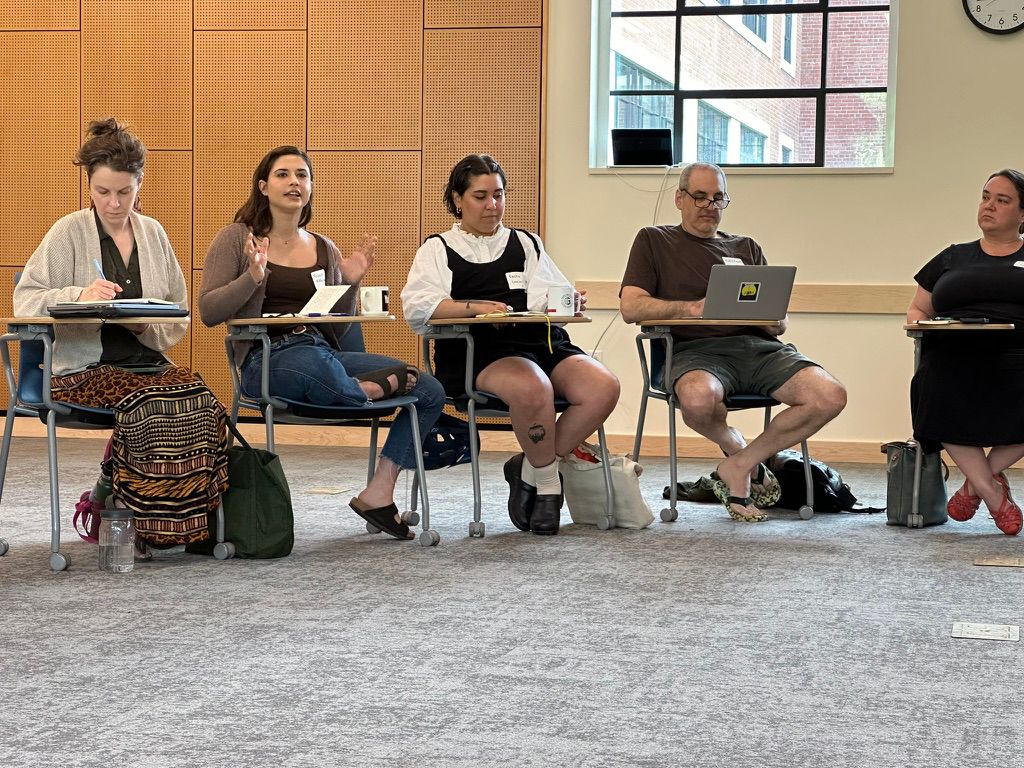

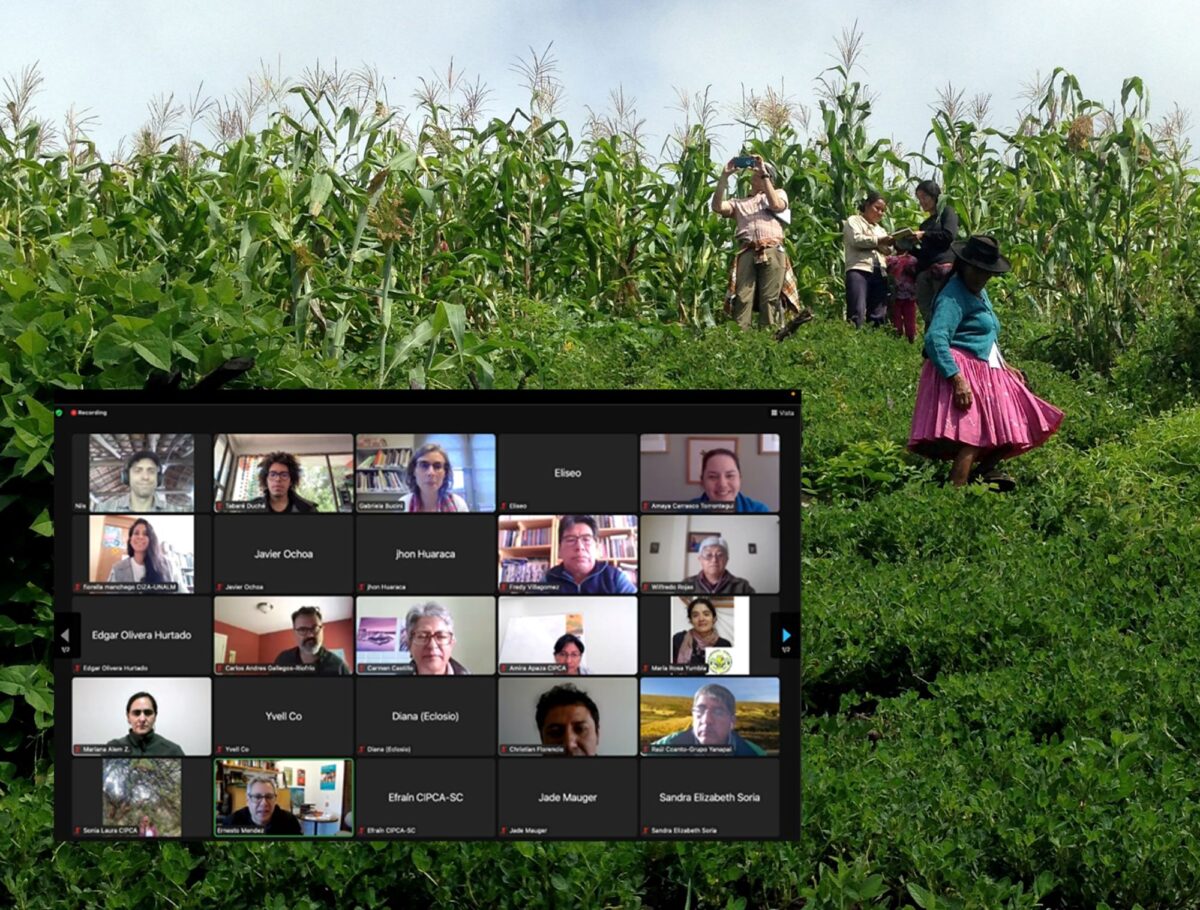

Beyond the awarded funding, this grant program will offer months-long engagement, bringing together faculty and co-investigators into a shared space of co-learning and reflection. The cohort’s first meeting took place on Friday, May 24 to share research experiences, practice active listening, and discuss the pillars of agroecology. Representatives from all six projects joined the first meeting; their projects include evaluating ecosystem health through citizen science, exploring agroecological practices in traditional working landscapes, linking conservation efforts and food security through agroecology, participatory pre-breeding of culturally significant crops, examining community health and Black agrarian agroecology, and a pilot project with trans, queer, and BIPOC farmers through the UVM Food Justice Lab. These smaller grants are pivotal in enabling innovative research that connects academic inquiry with real-world applications, fostering sustainable practices and enhancing food security across various communities.

Left: Anaka Aiyar, Quinn DiFalco, M. Salim Uddin, and Josh Farley participate in the discussion. Center: Harvest at New Farms for New Americans, Burlington, VT, photo courtesy of Quinn DiFalco. Right: Katie Horner, Krizzia Soto-Villanueva, Andy Kolovos, and Teresa Mares listen while Michelle Nikfarjam summarizes her segment of research for the “Histories and continuities of working landscapes and livelihoods in New England: Agroecological case studies of agroforestry, fiber farming, and hunting” project.

Project Summaries

Building a Baseline: Evaluating Ecosystem Health at NFNA through Citizen Science

This grant — led by co-principle investigators Quinn DiFalco (CALS) and Joshua Farley (CDAE) — will address a number of concerns with the New Farms for New Americans (NFNA) program, in which intergenerational families, the majority of whom are resettled refugees, grow crops each year at the Ethan Allen Homestead in Burlington, Vermont. While the NFNA is successful, several aspects of the program will be addressed, including conservation and soil management, reduced till land access, climate-smart education, and perennial agriculture. While DiFalco’s and Farley’s project will directly benefit the NFNA — with resilient farming and training opportunities — there will also be an effort to analyze and assess the ecological health of the floodplain.

Histories and continuities of working landscapes and livelihoods in New England: Agroecological case studies of agroforestry, fiber farming, and hunting

How does agroecology help us to bettered understand the histories and continuities in agroforestry, fiber farming, and hunting in the Northeast? Teresa Mares (CAS) aims to find out with their project. Understanding that while the Northeast food system is a mosaic of traditional, technological, and emerging practices for sustaining livelihoods, it’s also grappling with significant ecological, economic, and sociopolitical changes impacting the relationships between people, place, and our animal and plant relations. Mares’ lab plans to trace these impacts across three case studies: subsistence hunting, agroforestry, and fiber farming.

No Monkey Business – Linking Conservation of Gibbons, Agroecological practices, and Food Security among tribal communities living in a bio-diversity hotspot in India

While most of the projects awarded from this grant are focused on agroecology practices in the Northeast, Anaka Aiyar (CALS) and co-principal investigator Divya Vasudev (Conservation Initiatives) strive to develop a framework to understand and strengthen the linkages between agri-food systems, the health of gibbon populations (an Apex biodiversity species), and food security concerns of the forest-dwelling community living in a biodiversity hotspot in a resource-constrained context in the hilly and densely forested north-east of India. Ultimate, Aiyar and their partners want to understand the challenges of agroecological practices, conservation, and socio-economic considerations for local communities and develop a framework where goals for sustainable agrifood systems can be coupled with social–ecological systems and conservation.

Participatory pre-breeding of culturally significant crops, Sorghum and Mungbean

In the global south, participatory plant breeding (PPB) has historically been prioritized and pursued. Daniel Tobin (CDAE) and co-principal investigator Jasmine Hart (CALS) propose to examine the “intermediate zones,” areas with fewer agroclimatic stressors but barriers to end user adoption of improved plant varieties. By collaborating with the BIPOC-led organization, Ujamaa Cooperative Farming Alliance, Tobin, Hart, and their partners will address the lack of literature prioritizing PPB with a culturally meaningful perspective for the diaspora of many cultures found in the US.

Relationship between Black Agrarian Agroecology and Community Health Outcomes: A Place Based Pilot Study Among African American Women

Using a holistic approach with both quantitative and qualitative data, Teresa Leslie (CALS) plans to explore the perceived health outcomes of the African diaspora. Specifically focusing on African American women in the Boston region, Leslie will utilize a community engagement framework to compile deep and embedded insights into perceptions of health and well-being, understanding and experiences with agroecology, and the perceptions and beliefs around the influence of agroecology on food systems and health. Ultimately, Leslie anticipates these insights can inform and establish culturally appropriate health hubs within urban agricultural spaces.

Three UVM Food Justice Lab pilot projects with trans and queer farmers and farmers of color in New England

Agroecology programs at universities in the United States are increasingly focusing on the social side of agroecology, often framed as “food sovereignty” and studied with community or participatory action research. However, many of those universities have yet to integrate and institutionalize these frameworks to their potential. The IfA’s own mission emphasizes this participatory action research method to advance just transformations in food systems. Working within that framework, and understanding that food justice scholarship must be grounded in community practice, Ike Leslie (CALS, UVM Extension) will use this award funding to develop three pilot projects with trans and queer farmers and farmers of color in New England, ultimately establish long-term relationships and support UVM-community collaborations centered on applied food justice, agroecology research, teaching, and practice.

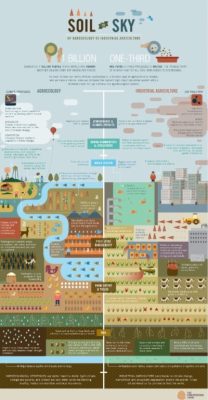

Food systems are complex, and policies influencing them exist at multiple levels (local, national, regional, international) and in different domains. These include access to land and tenure regulations, seed laws, food safety regulations, water use mechanisms, market development, trade rules, state programs for rural women or youth, and regulations regarding social organization, among many other things. They also address community processes, ways of interacting and customary law. Policies are not only state-led. People’s agroecological processes or indigenous governance are equally meaningful forms of policy co-creation.

Food systems are complex, and policies influencing them exist at multiple levels (local, national, regional, international) and in different domains. These include access to land and tenure regulations, seed laws, food safety regulations, water use mechanisms, market development, trade rules, state programs for rural women or youth, and regulations regarding social organization, among many other things. They also address community processes, ways of interacting and customary law. Policies are not only state-led. People’s agroecological processes or indigenous governance are equally meaningful forms of policy co-creation.

We invite summaries of between 250 and 500 words. If selected, you will be invited to draft a longer article of around 2000 words. We invite two types of contributions:

We invite summaries of between 250 and 500 words. If selected, you will be invited to draft a longer article of around 2000 words. We invite two types of contributions:

Critical Adult Education in Food Movements

Critical Adult Education in Food Movements