Do you have experiences, examples, stories or insights about how policy can support (or undermine) agroecology? Consider submitting an article to the first issue of the newly named magazine, “Rooted: Agroecology, Cultures and Foodways” [formerly ‘Farming Matters’].

Available as PDF in English, Spanish, French and Portuguese

Rooted magazine is a new platform for the exchange of voices, perspectives and knowledge of food producers and others at the forefront of action to transform food systems through agroecology.

For the inaugural edition issue of Rooted, planned for early 2024, we are warmly inviting you to contribute grounded stories that:

- demonstrate the potential of policies to support the practice and spread of agroecology for food systems transformation;

- reflect on how peoples’ advocacy, organizing and political processes are shaping relevant policies for agroecology.

We are especially looking for lessons and insights from real experiences.

How policies matter for agroecology

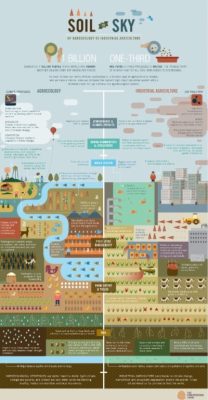

Agroecology has continued to gain momentum and recognition for its transformative potential to respond to today’s crises and to achieve food sovereignty. There is a growing evidence base about the impact of agroecology, and incidental policy support. Yet there are still many systemic barriers that prevent agroecology from achieving its potential in transformations towards more just and sustainable food systems.

Food systems are complex, and policies influencing them exist at multiple levels (local, national, regional, international) and in different domains. These include access to land and tenure regulations, seed laws, food safety regulations, water use mechanisms, market development, trade rules, state programs for rural women or youth, and regulations regarding social organization, among many other things. They also address community processes, ways of interacting and customary law. Policies are not only state-led. People’s agroecological processes or indigenous governance are equally meaningful forms of policy co-creation.

Food systems are complex, and policies influencing them exist at multiple levels (local, national, regional, international) and in different domains. These include access to land and tenure regulations, seed laws, food safety regulations, water use mechanisms, market development, trade rules, state programs for rural women or youth, and regulations regarding social organization, among many other things. They also address community processes, ways of interacting and customary law. Policies are not only state-led. People’s agroecological processes or indigenous governance are equally meaningful forms of policy co-creation.

These (sometimes) disparate policies shape the governance of food systems: the way in which decisions about food and farming are made, by whom and where. Very few examples exist of policies that effectively enable agroecology. When they do exist, meaningful implementation is often lacking. So what can we learn from instances where policies for agroecology do exist and work?

This issue of Rooted aims to gather and consolidate concrete examples of how policies can facilitate the development of agroecological food webs, and enable the transition away from industrial food and farming systems.

Your contribution

You are invited to contribute your stories and experiences of policies that strengthen agroecology. We are particularly interested in delving into the following questions:

● How have actors in the food system and their experiences been able to shape policies (and their implementation) that support a transformative agroecology?

● How can policies be developed and implemented so that they provide a solid basis for agroecology to thrive without inhibiting the autonomy of food system actors?

● Are there examples of policies that have facilitated the use and spread of agroecological practices or encouraged the social relations that support it? What were the conditions that made these effective?

● What kinds of policies exist that reconfigure the power of corporations in the industrial food systems and support the agency and autonomy of food producers?

● What can we learn from existing policy for the implementation of the UN Declaration on the Rights of Peasants at national levels?

● What kind of people’s policies (including processes, proposals, convergences, governance arrangements and vision statements) have been created in support of agroecology and how?

● What are the lessons from these experiences for the practice, science and/ or movement of agroecology?

How to submit your contribution

We invite summaries of between 250 and 500 words. If selected, you will be invited to draft a longer article of around 2000 words. We invite two types of contributions:

We invite summaries of between 250 and 500 words. If selected, you will be invited to draft a longer article of around 2000 words. We invite two types of contributions:

1) ‘Testimonies’: which detail lessons from experiences from the ground and reflect on their wider relevance. What did you do? What worked (or not?) and why (or not)?

2) ‘Opinion/ perspective pieces’: these should also be grounded in concrete experiences, but focus on presenting a cutting-edge proposal for the future.

We will give priority to contributions from authors that have been involved in the experience themselves. We will seek to present a balance between knowledge from practice and academic contributions.

No writing experience is required: our editors will provide ample support where desired.

Please submit your summaries (in English, Spanish, Portuguese or French) to: info@cultivatecollective.org

The deadline for submissions is 10 August 2023.

————————

Rooted is published by Cultivate!, the Centre for Agroecology, Water and Resilience of Coventry University and the Institute for Agroecology at the University of Vermont. We work in close collaboration with LEISA Revista de Agroecología and AS-PTA’s Revista AgriCulturas. We proudly carry forward the long legacy of Farming Matters magazine.

We will provide simultaneous Spanish translation for this event.

We will provide simultaneous Spanish translation for this event.

This online event will provide simultaneous Spanish translation.

This online event will provide simultaneous Spanish translation.

Critical Adult Education in Food Movements

Critical Adult Education in Food Movements