Agroecological education in the Andes

Strategies for community-centered co-learning

Transitions toward just and sustainable food systems are complex processes involving evolving relationships between communities of plants, animals, fungi and bacteria, as well as conscious action by growing numbers of people with shared values. At the Institute for Agroecology (IFA), we focus on transformative learning as the fundamental component of building movements and co-creating understandings that can lead to positive change in agroecosystems, communities, territories and institutions.

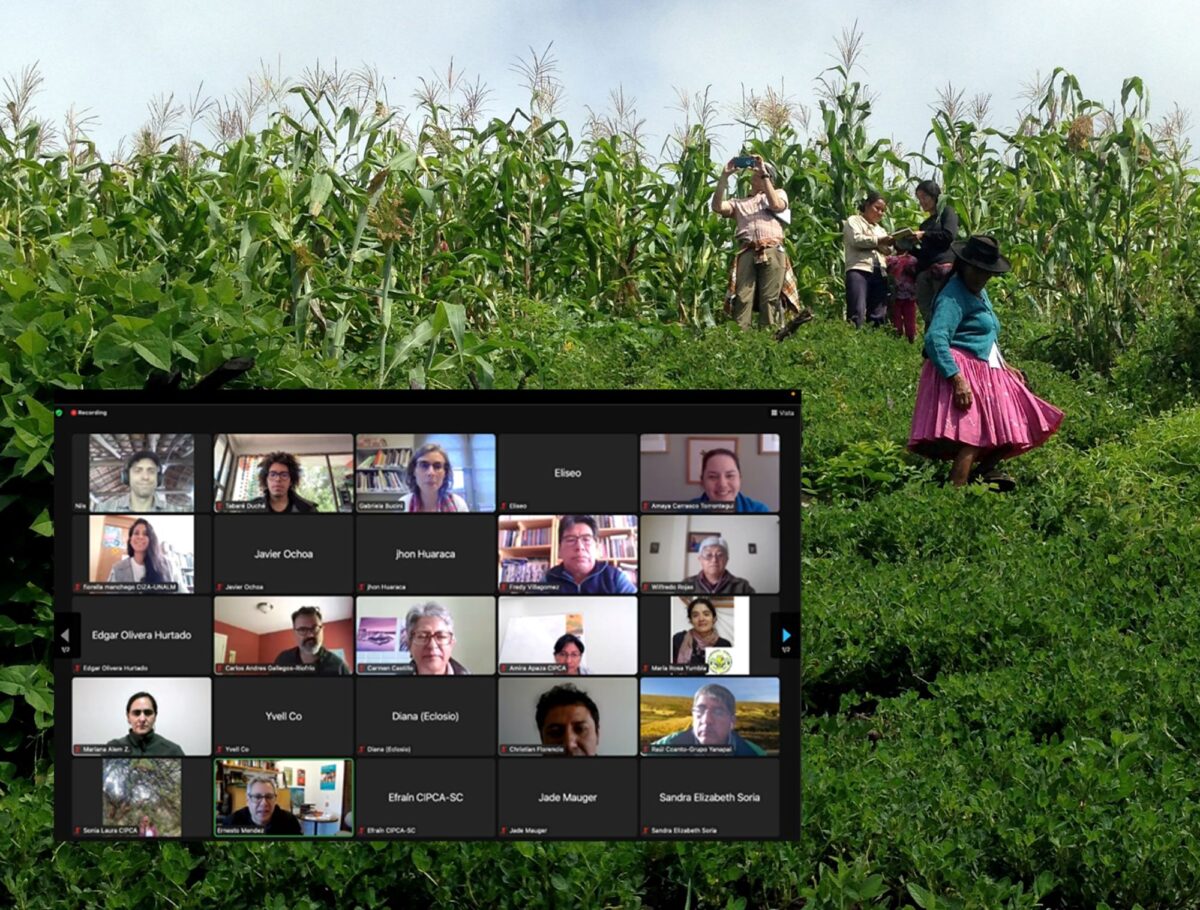

Over the past two months the Institute’s Agroecology Support Team facilitated an online International Course on Agroecological Transitions with the participation of adult professional students from Bolivia, Ecuador and Peru.

The six-week course, entitled Agroecology for Life: Problem-solving in Transition Processes, was designed as a primer in Participatory Action Research for researchers, professionals and members of social organizations that accompany communities in processes of transformation using agroecological principles.

Taking full advantage of the tools of digital online education, the course combined lively synchronous discussion sessions with guest speakers, asynchronous forums, videos, readings from popular press and academic sources, songs and Andean prayers asking permission of Mother Earth.

As a formation (i.e. learning) process created to support the Andes Community of Practice of the Global Collaboration for Resilient Food Systems (CRFS), “the bedrock of this educational effort is the deep context of Andean agriculture, its peasant knowledge systems and indigenous cosmovisions,” according to course co-facilitator and IFA Research Associate Nils McCune.

This context includes the language and culture of Quechua and Aymara peasant farmers in the Andean region of tropical mountains and vertical archipelagos reaching from the Pacific Ocean to the Altiplano desert at elevations above 13,000 feet above sea level, as well as recent sociopolitical change emerging from new constitutions in 2008 and 2009 that recognized the “plurinational” character of Ecuador and Bolivia, respectively. In addition to the colonial language, Spanish, indigenous languages Kishwa and Shuar were recognized as official languages by Ecuador’s Constitution of 2008, while Bolivia’s 2009 Constitution recognized 37 official languages.

Indeed, the institutional context for agroecological transitions is unique in the Andes. Ecuador was the first country in the world to incorporate the Rights of Nature into its Constitution, and Bolivia followed suit in 2010 with the Law of the Rights of Mother Earth, which grants all nature equal rights to humans. Both countries have constitutions that recognize the state’s responsibility to guarantee food sovereignty, the right of peoples to build, control and defend their own food systems according to their knowledge and culture.

This context shows the need for “a more horizontal, humble approach that sees the relativity of academic knowledge and NGO practice, one that recognizes rural communities and food producers as the fundamental pillar of agroecology,” according to Freddy Congo, an Ecuadorean popular educator with the Union of the Peoples of Moreles (UPM) in Mexico, winner of the Rural Vermont’s Agroecology, Education & Organizing Fellowship Award, and participant in the course.

In all three countries, the Agroecology Support Team works directly with universities, research centers and local NGOs carrying out community- and territory-level processes of agricultural research using methods like farmer research networks, agroecology peasant schools, as well as seed-saving and agrobiodiversity research.

Knowledge co-creation, mobilization, and exchange among these projects is one of the goals of our work, so a central theme of the course in on fostering participatory methodologies.

We need spaces that connect us in a broad and diverse fabric, in order to recognize the diverse ways of perceiving agroecologies on the road to food sovereignty, the emancipation of our peoples, social justice and the good life. The course Agroecology for Life is one of those spaces, where a variety of ways of thinking, feeling and being people are shared in cooperation, co-construction and co-learning.

Tabaré Tonalli Aquimín Duché García

Postdoc at El Colegio de la Frontera Sur (ECOSUR) in Mexico and course participant

Georgina Catacora Vargas, the Bolivian agroecologist, president of the Latin American Scientific Society of Agroecology (SOCLA) and guest lecturer in the course, argues that “our methodologies are the lenses with which we characterize and reflect on reality, as well as the reflection of our epistemological position, the way in which we (co-)create knowledge.” Her guest appearance in the course was a highlight mentioned by many participants in course evaluations.

Beyond the conceptual and methodological aspects of the Agroecology for Life course, an emerging property of the effort is the idea of building and consolidating a learning community: a space for mutual respect, cross-pollination, and exchange. As Renato Pardo, a course participant and program officer at PROSUCO in Bolivia, put it, the strength of the course is in the “possibility of sharing experiences with other institutions and other professionals working on similar themes.”

We’ve been so pleased with how the course has turned out, and have experienced and observed so much growth and integration as a result. We’ve also received positive feedback from our partners. In a recent communication, Claire Nicklin, Andes CoP Regional Representative for CRFS, noted “the IFA team did a fantastic job of facilitating a warm and collaborative space for practitioners to meet and discuss agroecological transitions.”

The course was co-facilitated by Gabriela Bucini, Nils McCune and Ernesto Méndez.