As mentioned in our previous blog post, representatives from the world’s nations are currently gathering in Montreal for the UN Biodiversity Conference (COP15) on the Convention on Biological Diversity (CBD). The goal of the meeting is to adopt a “Global Biodiversity Framework” which will guide international collaboration to reverse dramatic losses of global biodiversity for the next 30 years. Yet, to our peril, agroecology and agrobiodiversity have been marginalized in these debates.

I (Colin) grew up on a farm in the Canadian Prairies and am still charmed by the region’s big skies and agricultural landscape. Seas of yellow canola flowers blossoming as far as the eye can see. Wheat fields, gently swaying in the wind, stretching from fencerow to fencerow. Beautiful blankets of color, pleasing to the eye.

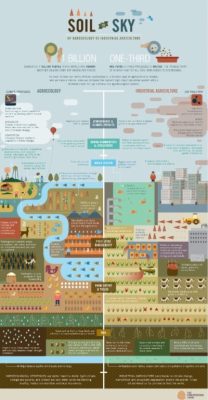

These simplified agricultural systems have an alluring beauty on the surface, but they are devoid of the potential diversity of crops and livestock that, when integrated, allow for a more efficient and synergistic use of resources. What’s more, they are hostile towards wild biodiversity through the elimination of habitat, the application of herbicides and pesticides and the degradation of soil health.

Nevertheless, the intensification of industrial agriculture in this image remains the dominant model being promoted globally – a model of agriculture that must be transformed if we are to reverse global biodiversity losses and sustain life on Earth for our grandchildren. That is why the United Nations set up the Convention on Biodiversity (CBD) in 1992, and why, 30 years later, with biodiversity losses still accelerating, decisive action by governments is vitally urgent.Where is agricultural biodiversity in global decision-making about biodiversity conservation?

The COP15 meeting comes during a mass extinction event. A high percentage of global biodiversity, and biosphere integrity, is at risk, and threatened especially by the dominant economic and social drivers of industrial food systems. In short, the stakes for this CBD meeting are unfathomably high.

The evidence from FAO, IPBES and IPCC has clearly established that agriculture and land use change are among the main drivers of biodiversity loss. Large-scale, industrial-style agriculture threatens 86% of the 28,000 endangered species and, in a blow to food security and resilience, these farming systems are responsible for the loss of most of our genetic diversity in crops and livestock over the last century. Currently, only 12 plant species and 5 livestock breeds make up 75% of the world’s industrial food system, with just 3 species (wheat, rice and corn) providing half the calorie intake. According to the IPBES Global Assessment, these genetically shallow agricultural systems are increasingly vulnerable to pests, pathogens, climate change and other factors.

Notoriously sidelined in UN negotiations, however, is a focus on highly threatened ‘agricultural biodiversity’ – the major sub-set of biodiversity in the areas where people live and work. It includes all the biodiversity, above and below ground and in waters, which supports our food and agricultural systems, provides food, fiber, shelter, clean water, medicine and underpins vital ecosystem functions.

Without deeply transforming industrial food systems towards ones that will prioritize agroecological systems of production, the losses of agricultural biodiversity will proceed unabated, placing the very basis of human existence in peril.

Instead, CBD debates on biodiversity have come to focus on proposals for setting aside large areas of land to conserve pristine nature. The touted 30×30 campaign, for example, proposes setting aside 30% of territories in Protected Areas by 2030. These types of programs, however, often harm and displace millions of knowledgeable, biodiversity-conserving Indigenous Peoples and local communities from their traditional territories.

Such a focus distracts attention from what is happening on the other 70% of land, where there’s a drive to intensify agricultural production using biodiversity- and habitat-reducing homogeneous monocultures. This aligns with the power structures of the industrial agrifood system. It intentionally marginalizes and displaces the people who have the greatest history, sophisticated knowledge, and potential to protect, restore, and enhance highly heterogeneous agricultural biodiversity.

Biodiverse agroecology – a compelling alternative paradigm to build back agricultural biodiversity and confront our intersecting crises

Indigenous Lepcha farmers in Sikkim, India practicing traditional agroecological seed saving and agriculture

Agroecology in Vermont, USA

Women-led agroecology in Kenya

Photo credit: LEISA India

A growing chorus of scientists, institutions, civil society organizations, and small-scale food providers have gotten behind agroecology as an alternative paradigm for organizing and transforming food systems.

Biodiverse agroecology involves the application of ecological principles to the design and management of sustainable agroecosystems, drawing from Indigenous and local knowledge, and directly addressing the political changes needed to transform food systems. It focuses on redesigning agricultural practices, policies, networks and governance, based on a set of principles that emphasize biodiversity, resilience, people’s knowledge, the fundamental role of women and the importance of food sovereignty.

While industrial food systems are destroying biodiversity, smaller-scale agroecological farms are at the forefront of conserving and enhancing agricultural biodiversity, and improving ecosystem functioning, while producing the majority of the world’s food. Peasant, indigenous and territorially rooted agroecology is vital to maintaining agricultural biodiversity, within farm plots and across rural landscapes. These agroecosystems conserve the heterogeneity and variety within species and among species at community and ecosystem levels.

There are countless examples of agroecology emerging around the world. Agroforestry systems enhance biodiversity through incorporating trees and shrubs into cropping or livestock lands, providing resiliency against climate change and improved rural livelihoods. The adoption of intercropping, such as in the Mesoamerican milpa systems, where corn is planted alongside beans, pumpkin, chili, and other vegetables create rich mosaics of biodiversity in farms and landscapes. In India, Amrita Bhoomi trains farmers on Zero Budget Natural Farming – a local agroecological method that needs no external inputs, very little water, and relies on natural processes. These agroecological approaches not only enhance agricultural biodiversity in farmers’ fields but also provides habitat for the biodiversity in the surrounding ecosystems, to the wider benefit of people and the environment (see infographic below).

By working with – not against – nature, and diversifying our farms, landscapes, fishing waters and the foods we eat, agroecology supports biodiversity, contributes to the majority of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) and promotes resilience. All while supporting livelihoods and some of the healthier diets on the planet.

To build up biodiverse agroecology, it is important to transform the enabling environment and confront the power of corporations and agribusiness in maintaining the status quo. This requires prioritizing, in the post-2020 Global Biodiversity Framework, the inclusion of the implementation of already agreed upon actions that sustain agricultural biodiversity. Specifically, we need to scale out peasants’ dynamic management of biodiverse agroecology while respecting indigenous peoples’ and peasants’ collective rights to seeds, livestock breeds, territories and forms of production.

Regardless of the outcomes of this year’s CBD /COP15, civil society actors should engage in broad, coordinated actions and movement building to continue to strengthen agricultural biodiversity in communities and policies. Only in this way can we truly transform food systems, stem the loss of agricultural biodiversity and address the intersecting crises of inequality, diet-related illness, climate change, and hunger.

Agroecology in Action from Rich Appetites on Vimeo.