By / Por: Luis Alexis Rodríguez-Cruz

This essay was written by Luis about his experiences assisting Aura M. Alonso-Rodríguez – both ALC members – with her research en El Yunque. This essay was originally published in Spanish in 80 grados and then translated by the author and published on www.luisalexis.com. Here’s more about Aura’s research.

This essay was originally published in Spanish at 80 grados. It was translated by the author and published on www.luisalexis.com.

I was thinking of two things while walking: that my legs could not hold me anymore and that I wanted to see a coquí, Puerto Rico’s endemic frog. We had been within the green labyrinth of El Yunque, Puerto Rico’s tropical rainforest, for almost four hours. Although I wanted to look up and appreciate the plethora of stars, I kept my gaze down so that the flashlight on my head would light the way. Falling down on one of those paths, full of rocks and roots, while carrying a backpack full of scientific equipment, is not a pretty picture. There were times when I slipped, but still had not fallen. I was in the back of the line, walking slowly to see if I could spot a coquí, but without missing the pace of the team. “Look, Luis,” Aura said after a while. And there it was, quiet on a log, ready for the photo. After that, she asked us to turn off our flashlights.

Aura Alonso-Rodríguez is an ecologist. She studies human and climatic impacts on tropical ecosystems through insects. Two other people and I accompanied her on her once or two times-a-year pilgrimage to El Yunque, under the new moon. We were assisting her in her research, focused on understanding the impacts of Hurricane Maria on moth (nocturnal butterflies) communities. It is under the new moon that this type of sampling can be done effectively: the darkness reduces competition between the light from the trap and from the moon, thus attracting more moths.

The voices of the rainforest multiplied and amplified once we shut off the lights. To be immersed in the darkness of our rainforest and to listen to its sounds is not an opportunity that I am often given. In that moment, I finally looked up to the skies and appreciated the stars without fear of falling. As a drizzle began, we turned on the lights, and continued our walk back to the where we started.

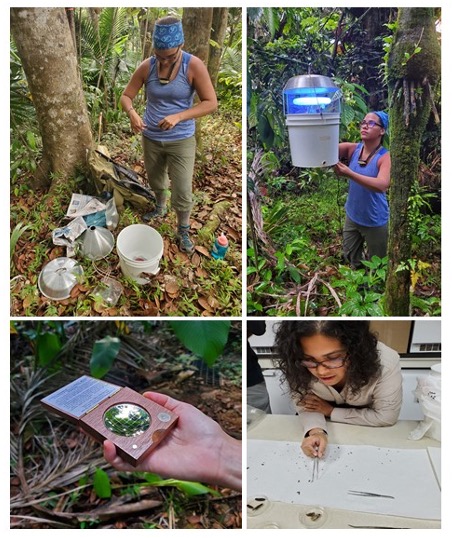

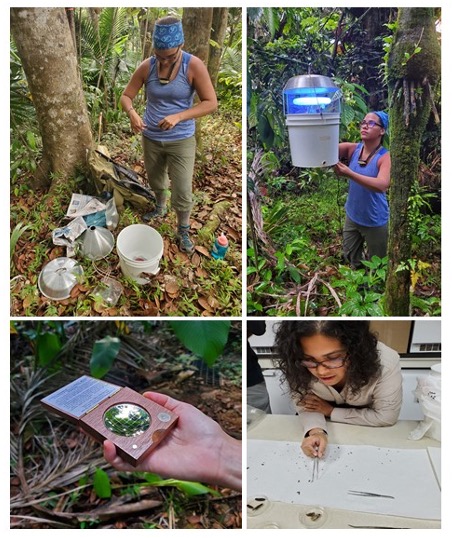

We arrived around 6:30 P.M. to the El Verde field station, the research center of the University of Puerto Rico located in El Yunque. The objective was to go to the three spots that Aura selected, where we would place three traps with ultraviolet bulbs that would attract the moths. We carried three 25-pound batteries into the rainforest; each of us with a backpack full of equipment and several bottles of water and snack bars. It was almost 11 P.M. by the time we got back to the parking lot. The rain helped disguise the sweat and tiredness of our bodies.

That new-moon-weekend in July 2020 brought back memories of when I did research in the field, but it also reminded me of how complicated and complex it is, as many things are out of our control. Especially, when there is an ongoing pandemic. We returned to the house while listening to the symphony of our stomachs. And although we were tempted to open a few beers and socialize, we opted to go to sleep after eating, as we had to return to the forest around 5:00 A.M. When I saw Aura’s disappointment and frustration when finding the traps turned off the next morning, I knew we should have had at least one beer before going to sleep.

I arrived in Rio Grande, one of the municipalities where El Yunque is located, Friday afternoon. Aura and I met at a local supermarket to buy food for the weekend. The last time we saw each other was two months earlier, in Vermont, where we are studying. We stared at each other for a few seconds, and then hugged. Obviously, breaking pandemic protocols made us feel bad — even though we had been in isolation for a long time, preparing for that sampling weekend at El Yunque. It felt good to escape from the south of Puerto Rico, where I live. The drought, plus the Saharan dust, had the area all covered in brown and misty landscapes. These episodes of severe drought are becoming more frequent and intense in the Caribbean. Puerto Rico, like most islands in the region, is expected to see increasing temperatures due to climate change. Seeing so much green, while following Aura towards the house near the rainforest where we would be staying, was almost magical. “It is very dry here too, even if it doesn’t look like it” –she told me, as we got the equipment out of her car.

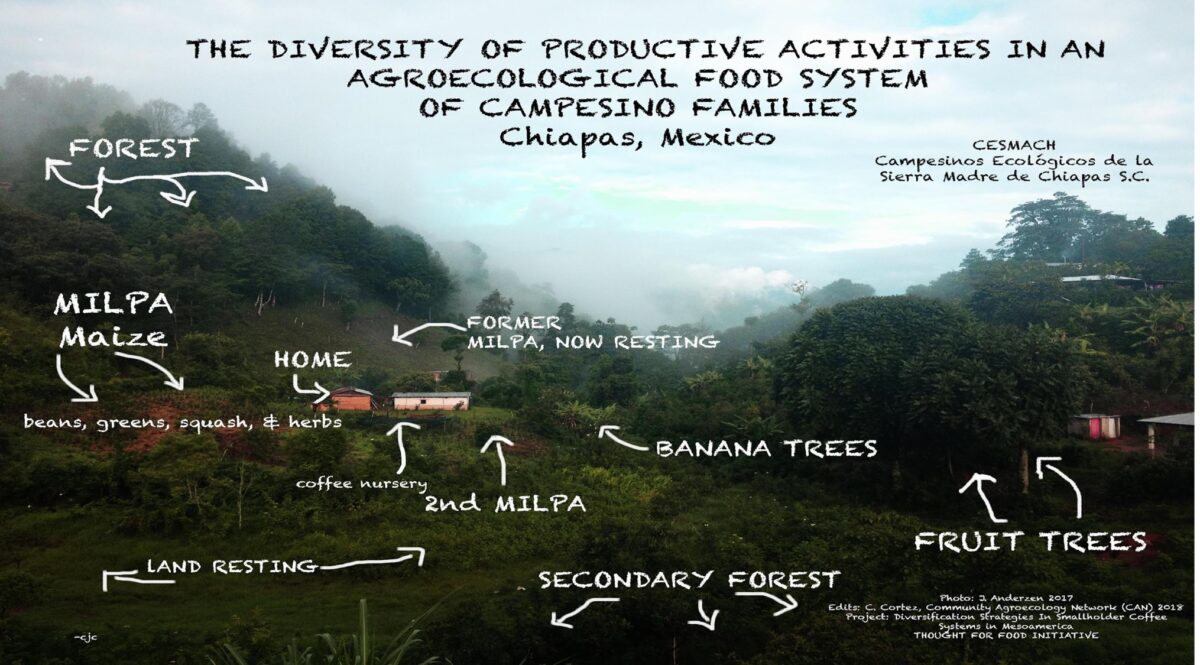

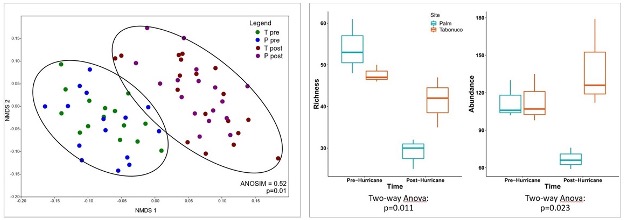

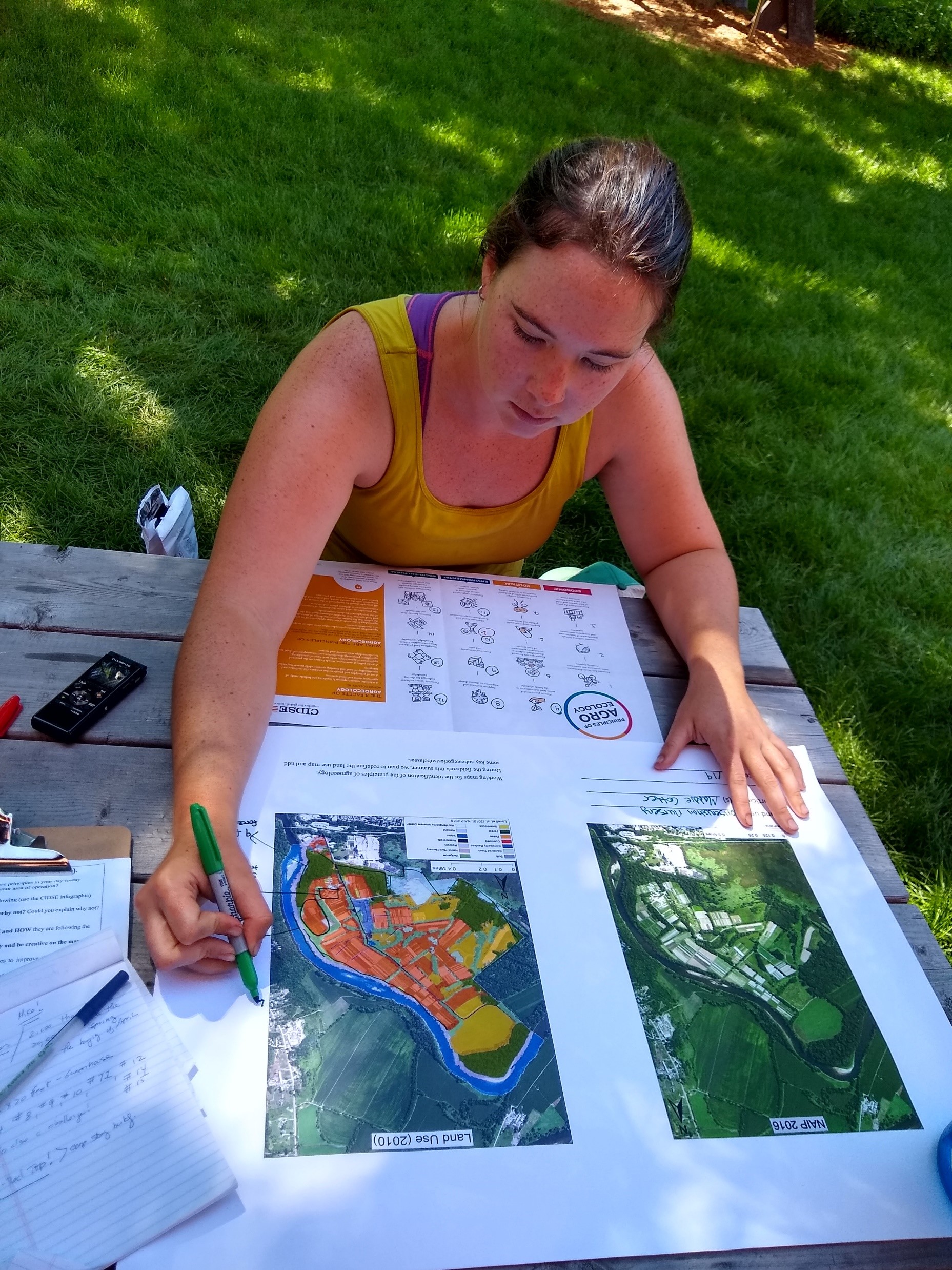

Aura has been collecting moths in El Yunque since the beginning of 2017. Little is known about them. In particular, their role in nocturnal pollination, which is important for the ecosystem, and for agricultural production. Aura told me that, “[all] butterflies belong to the order Lepidoptera, and more than 90% of them are nocturnal. The last study about them in Puerto Rico was done in 1998 (1); 1,045 species of butterflies were estimated, of which 26% are native to the archipelago.” The objective of her project was to know the degree of difference, if any, in moth communities (assemblages) in two forest areas in El Yunque: one dominated by Sierra Palm (Prestoea montana), and the other by Tabonuco trees (Dacroydes excelsa). There are 4 types of forests and various microclimates that make El Yunque a special place. To that we add its cultural and traditional significance, particularly the one that our Taino ancestors gave it. Unfortunately, human impacts, such as light pollution, solid waste mismanagement, and poorly planned constructions, together with natural impacts that are intensifying due to climate change (also human-driven), such as droughts and stronger storms, have increased the vulnerability of our national forest, producer of water, air and beauty. People like Aura seek to understand how, specifically, these impacts harm their biodiversity, in order to outline effective ways for conservation.

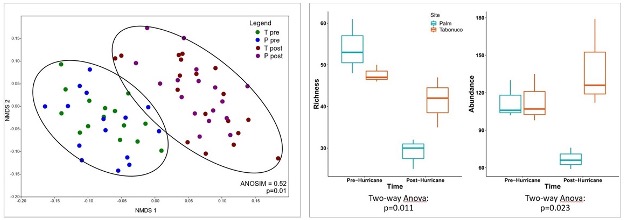

I underlined “was” in the paragraph above because Aura’s study now revolves around understanding how those assemblages changed with the impact of María, a 2017 category 4 hurricane that caused damage or death to 23-31 million trees in Puerto Rico [2]. “[Our study] is one way of better understanding the response and recovery of the forest to this impact.” Preliminary data from the study suggests that the assemblages were completely changed by the impact of the hurricane, regardless of forest type [3]. Nonetheless, after the hurricane, the number of individuals (abundance) and the number of species (richness) was higher in the area dominated by Tabonuco trees. “These trees are strong, they create underground connections between them, unlike Sierra Palms that do not provide good shelter due.” Therefore, given that the impacts will continue to occur, if we want to safeguard the biodiversity of the forest, it is important to conserve those areas dominated by Tabonuco, most of which are remnants of mature forest. Meaning that these areas have not been affected by human disturbances. Aura is confident that future samplings will shed more light on that preliminary conclusion.

As we walked under the subtle light of dawn to where we had left the traps, Aura pointed out areas and described how they were like before the hurricane. Frankly, everything looked the same to me. It was remarkable how embedded she was in the landscape and the connection she had with the forest. I told the team that if they were following me, we would have already gotten lost and would never find where we left the traps. “I grew up in the forest,” Aura said. And just as she had seen El Yunque transform, she also saw how the mountains of Carraízo, where she was raised, transformed throughout her childhood. Witnessing the change of the landscape catalyzed questions that she would later answer through her scientific work. “What do you feel?”, I asked her when we got to the first spot and saw the light off. Although there was a hint of anger and frustration, Aura took a deep breath and began to tell us the possible causes. She had checked the voltage of the batteries and tested them before the weekend. But as she said, it was not in her control that they got damaged. Sometimes one wastes so much energy in pondering over something one does not control. And now, whenever something similar to the “battery situation” happens to me, I think about how Aura responded to it.

We proceeded to remove the trap — we noticed that several moths were caught, but not the number that she expected. Yes, seeing their corpses raised uncomfortable questions in me. But their life cycle is very short and sampling once or twice a year does not harm the population―I said to myself. When collecting all the equipment, Aura took out a densiometer and together with the other colleague measured the canopy to see how much light enters the area. By comparing the canopy cover data that Aura took before and after Hurricane Maria, she can determine how much the forest has recovered since the hurricane. Then we walked up the mountain to find the second trap off. The same happened with the third. And what do you do when an experiment goes wrong in El Yunque? Well, you go for a dip in a swimming hole.

While floating in the river, Aura went over different options on how to deal with the setback. She would soon have to return to Vermont, and coinciding with the new moon in Puerto Rico is not an easy thing. So, she had to re-sample to not miss the opportunity. The next day, when I had to go back to the hot south, we returned with charged batteries and set up a camera to see how long the light bulbs lasted. Before I left, I went with her to the laboratory to help sort the samples we collected the previous night. We were classifying all the moths by morphospecies, that is, by how they resemble each other. “That’s why I like insects, you have to learn how to see the details” -she said, while she explained to me how difficult it was to determine the real species, particularly that of the smallest ones.

I wanted to stay longer to help with the resampling, but responsibilities in the south required attention. As I was driving home along the old highway, it was clear how the green was turning brown. During that week, I could not get what happened in El Yunque out of my mind, plus my flat feet kept reminding me of how much we walked. Neither could I shake off that moment of silence and stillness when we turned off the lights. At the end of the week, Aura told me that they managed to acquire new batteries and that she decided to repeat the sampling the following month. Putting the camera served to check how long the bulbs were on and thus be able to adjust their results.

There are three new moons this summer of 2021, so maybe I’ll be an assistant to my ecologist friend again. Meanwhile, I hope to educate myself more about Tabonucos, about where they are in Puerto Rico, and on what we can do as a society to protect them. As the song of Francisco Roque Muñoz says, “Un jacho de tabonuco, tengo yo para alumbrarme” (A piece of Tabonuco, I have to light up the way).

- Torres, J. A. y S. Medina-Gaud, 1998. Los insectos de Puerto Rico. Acta Científica 12: 3-41

- Feng et al. (2018) Rapid remote sensing assessment of impacts from Hurricane Maria on forests of Puerto Rico. PeerJ Preprints 6:e26597v1 https://doi.org/10.7287/peerj.preprints.26597v1

- Aura Alonso-Rodríguez. University of Vermont – Rubenstein School. (2019, October 29). Vegetation types influences the response of moth communities to hurricane disturbance in a tropical rainforest. [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6H9f0bIK0Ac

Buscando mariposas bajo la luna nueva en El Yunque – This essay was published originally in 80 grados (Puerto Rico) in March 12, 2021.

Iba caminando y pensando dos cosas: en que ya no aguantaba las piernas y en que quería ver un coquí. Llevábamos casi cuatro horas bosque adentro en El Yunque. Aunque quería mirar hacia arriba y apreciar el revolú de estrellas, tenía la mirada hacia abajo para que la linterna en mi cabeza iluminara el camino. Caerse en una vereda de esas, llenas de piedras y raíces, mientras se carga un bulto lleno de instrumentos científicos, no debe ser bonito. Hubo ocasiones en que resbalé, pero aún no me caía. Yo iba atrás en la fila, caminando lento para ver si lograba ver un coquí, pero sin perder el paso del equipo. “Mira, Luis”—dijo Aura al ratito. Y allí estaba, tranquilito en un tronco, listo para la foto. Luego de eso, ella nos pidió que apagáramos las linternas.

Aura Alonso Rodríguez es ecóloga. Estudia los impactos humanos y climáticos en ecosistemas tropicales a través de los insectos. Otras dos personas y yo la acompañamos en su peregrinación a El Yunque bajo la luna nueva para asistirle en su investigación, enfocada en entender los impactos del huracán María en las comunidades de mariposas nocturnas. Es bajo la luna nueva cuando este tipo de muestreo se puede hacer de manera efectiva: esa fase oscura ayuda a que la luz de la trampa no compita con la de la luna y así pueda atraer a las mariposas.

Los sonidos se intensificaron tan pronto apagamos las luces. No hablamos. Escuchar al bosque tropical más importante de Puerto Rico no es algo que se me da mucho. En ese momento pude mirar hacia arriba y apreciar el revolú de estrellas. Al comenzar una llovizna, prendimos las luces y continuamos.

Llegamos alrededor de las 630 P.M. a la estación El Verde, centro investigativo de la IUPI ubicado en El Yunque, para ir a los tres spots que seleccionó Aura, donde colocaríamos las tres trampas con bombillas ultravioletas que atraerían a las mariposas. Cargamos tres baterías de 25 libras cada una; cada quien con una mochila llena de equipo y varias botellas de agua y barritas para merendar. Ya eran casi las 11 de la noche cuando regresamos al estacionamiento. La lluvia ayudó a disimular el sudor.

Ese fin de semana de luna nueva en julio 2020 me trajo recuerdos de cuando hacía investigaciones en el campo, pero también me hizo recordar lo complicado y complejo que es, pues muchas cosas no están bajo nuestro control. Especialmente, cuando hay una pandemia en curso. Nos fuimos escuchando la sinfonía de nuestros estómagos. Y aunque nos tentaba abrir cervezas y socializar, optamos por ir a dormir después de comer, pues teníamos que volver al bosque alrededor de las 5:00 A.M. Al ver las bombillas de las trampas apagadas cuando volvimos al bosque y la cara de decepción y frustración de Aura, supe que debimos habernos bebido por lo menos una cerveza antes de dormir.

Yo llegué a Río Grande viernes por la tarde. Me encontré con Aura en un supermercado del área. La última vez que nos vimos fue dos meses antes, en Vermont, donde cursamos estudios. Nos quedamos mirándonos unos segundos y nos abrazamos. Obviamente, nos hizo sentir mal romper los protocolos pandémicos—aunque llevábamos mucho tiempo en aislamiento, preparándonos para ese weekend de muestreo en El Yunque. Me hizo bien escapar del sur. La sequía, más el polvo del Sahara, tenían la zona toda arropada de marrones y paisajes brumosos. Ver tanto verde, mientras seguía a Aura hacia la casa dónde nos quedaríamos, fue casi mágico. “No te creas, esto está bien seco aquí también” –me dijo, mientras bajábamos el equipo de su carro.

Aura lleva desde principios del 2017 recolectando muestras de mariposas nocturnas, de las cuales no se sabe mucho. Particularmente, su rol en la polinización nocturna, lo cual es importante, no solo para el ecosistema, sino incluso para la producción agrícola. “Las mariposas (todas) son del orden Lepidoptera y más del 90% de ellas son nocturnas. El último estudio en Puerto Rico fue en el 1998 [1]; se estimaron 1,045 especies de mariposas. El 26% son nativas del archipiélago.” ―me contaba Aura. El objetivo de su proyecto actual era conocer el grado de diferencia, si alguna, en las comunidades de mariposas nocturnas (ensamblajes) en dos áreas del bosque: una dominada por palma de sierra (Prestoea montana) y otra por tabonuco (Dacroydes excelsa).

En El Yunque hay 4 tipos de bosques y varios microclimas que hacen de él un lugar especial. A eso le añadimos su significado cultural y tradicional, particularmente la que le dio nuestros ancestros Taínos. Lamentablemente, los impactos humanos por contaminación lumínica, desechos sólidos y construcciones mal planificadas, en conjunto con impactos naturales que van intensificándose por el cambio climático (también causa humana), como las sequías y tormentas, han hecho que la vulnerabilidad de nuestro bosque nacional, productor de agua, aire y belleza, vaya en aumento. Personas como Aura, buscan entender cómo, específicamente, esos impactos perjudican su biodiversidad para entonces delinear maneras efectivas para la conservación.

Arriba subrayé “era” porque el estudio de Aura giró en torno a comprender cómo esos ensamblajes cambiaron con el impacto de María, huracán que causó daños o muerte de 23-31 millones de árboles en Puerto Rico [2]. “Es una manera de entender mejor la respuesta y recuperación del bosque”. Datos preliminares [3] de su estudio muestran que los ensamblajes cambiaron por completo por el impacto del huracán indistintamente del área. Sin embargo, después del huracán, el número de individuos (abundancia) y la cantidad de especies (riqueza) fue mayor en la zona dominada por tabonuco. “Esos árboles son fuertes, crean conexiones entre ellos bajo la tierra, a diferencia de las palmas de sierra que pierden las pencas y quizás no proveen buen refugio”. Por lo tanto, dado a que los impactos seguirán ocurriendo, si queremos salvaguardar la biodiversidad del bosque, es importante conservar esas zonas dominadas por tabonuco. Aura confía en que los próximos muestreos arrojarán mayor claridad a esa conclusión preliminar.

Aura señalaba áreas y describía cómo eran antes del huracán, mientras caminábamos hacia donde habíamos dejado las trampas. Francamente, para mí todo se veía igual. Era notable cuán inmersa estaba ella en el paisaje y su conexión con el bosque. Y más cuando no había amanecido del todo. Yo le comentaba que, si me estuvieran siguiendo a mí, ya nos hubiéramos perdido y nunca encontraríamos dónde dejamos las trampas. “Yo me crie en el bosque” ―me decía Aura. Y así cómo había visto a El Yunque transformarse, también vio cómo la montaña de Carraízo, dónde se crio, fue transformándose a través de su infancia. De ahí comenzaron preguntas que luego contestaría a través de su trabajo científico. ¿Qué sientes? –le pregunté cuando llegamos al primer spot y vimos la luz apagada. Aunque hubo una pizca de enojo y frustración, Aura respiró profundo y comenzó a contarnos las posibles causas. Ella había verificado el voltaje de las baterías y las había probado. Pero como ella dijo, el que se dañasen no estaba en su control. A veces uno se vuelve loco ponderando sobre algo que no controla. Y ahora, cada vez que pasa algo similar al papelón de las baterías, pienso en cómo Aura respondió a la situación. Procedimos a quitar la trampa—notamos que se atraparon varias mariposas, pero no la cantidad que se esperaba. Sí, me dio cosita verlas muertas. Pero su ciclo de vida es bien corto y muestrear una o dos veces al año no perjudica a la población. Al recoger todo el equipo, Aura sacó un densiómetro y junto a la otra compañera se midió la cobertura de dosel, para conocer cuánta luz entra a la zona. Comparando los datos de cobertura de dosel que Aura tomó antes y después del huracán María, ella puede determinar cuánto se ha recuperado el bosque desde María. Luego, nos fuimos jalda arriba para encontrar el segundo spot apagado. Pasó lo mismo con el tercero. ¿Y qué se hace cuándo un experimento sale mal? Pues, nos fuimos a nadar un rato a una charca del área.

Mientras flotaba en el río, Aura compartía distintas opciones para lidiar con la situación. Pronto tendría que volver a Vermont, y coincidir en Puerto Rico con la luna nueva no es cosa fácil. Por lo que había que volver a muestrear para no perder la oportunidad. Al otro día, cuando yo tenía que volver al sur caluroso, regresamos con las baterías cargadas y colocamos una cámara para saber cuánto tiempo duraba la bombilla prendida. Antes de irme, fui con ella al laboratorio para ayudarla a clasificar las muestras. Ese día también aprendí que decirles “polillas” no es lo mejor. Alevilla o mariposa nocturna. A cada ratito Aura me decía que estaba poniendo distintas mariposas juntas. Las estábamos clasificando por morfoespecie, o sea, por cómo se parecen entre sí. “Por eso me gustan los insectos, hay que saber ver los detalles” -decía, mientras me explicaba lo difícil que era determinar la especie real, particularmente de las más pequeñitas.

Yo tenía ganas de quedarme más días para retomar muestras, pero las responsabilidades en el sur requerían atención. Mientras guiaba por Fajardo, camino a Juana Díaz por la carretera vieja, se notaba bien claro cómo el verde se tornaba marrón. Durante esa semana, no me podía quitar de la mente lo ocurrido en El Yunque, más mis pies planos no paraban de recordarme todo lo que caminamos. Tampoco me podía desprender de ese momento de silencio y quietud cuando apagamos las luces. Al final de la semana, Aura me contó que lograron adquirir nuevas baterías y que decidió repetir el muestreo el mes siguiente. Poner la cámara sirvió para conocer cuánto tiempo estuvieron las bombillas prendidas y poder así ajustar sus resultados.

Hay tres lunas nuevas este verano 2021, quizás volveré a ser asistente de mi amiga ecóloga. Mientras tanto, conviene educarnos sobre los tabonucos, sobre dónde están y cómo conservarlos. Como dice la canción, “Un jacho de tabonuco, yo tengo para alumbrarme”.

Para conocer más sobre Aura y su trabajo, oprime aquí.

- Torres, J. A. y S. Medina-Gaud, 1998. Los insectos de Puerto Rico. Acta Científica 12: 3-41

- Feng et al. (2018) Rapid remote sensing assessment of impacts from Hurricane Maria on forests of Puerto Rico. PeerJ Preprints 6:e26597v1 https://doi.org/10.7287/peerj.preprints.26597v1

- Aura Alonso-Rodríguez. University of Vermont – Rubenstein School. (2019, October 29). Vegetation types influences the response of moth communities to hurricane disturbance in a tropical rainforest. [Video]. YouTube. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=6H9f0bIK0Ac

By

By

Camilla was a participant in this years Introduction to Agroecology course (PSS 311), part of our

Camilla was a participant in this years Introduction to Agroecology course (PSS 311), part of our

Being part of the ALC means committing to a process of inquiry and reflection that is both individual and collective. For several years, we have worked as a community of practice (CoP) to define norms, interrogate our own positionality and responsibilities, and make commitments to be agents of change both in our personal and professional realms. Given the growing awareness about systemic racism, we thought it was a good time to write a public statement about our position on broad issues of justice. We wrote the following statement together, as a community of practice, which reflects our values and articulates our commitments.

Being part of the ALC means committing to a process of inquiry and reflection that is both individual and collective. For several years, we have worked as a community of practice (CoP) to define norms, interrogate our own positionality and responsibilities, and make commitments to be agents of change both in our personal and professional realms. Given the growing awareness about systemic racism, we thought it was a good time to write a public statement about our position on broad issues of justice. We wrote the following statement together, as a community of practice, which reflects our values and articulates our commitments.