Author: Ava Murphey

Amaya Carrasco-Torrontegui chosen for Graduate Student Award for Outstanding Research and Scholarship

NEWS: ALC collaboration leads to a NIFA Research and Extension Experiences for Undergraduates grant

Looking for Moths Under the New Moon / Buscando mariposas bajo la luna nueva en El Yunque

NEWS: PAR projects led by ALC members receive funding

NEWS: ALC contributes chapter to Urban Agroecology book

NEWS: ALC Co-Director Ernesto Méndez selected for VP of Research fellowship

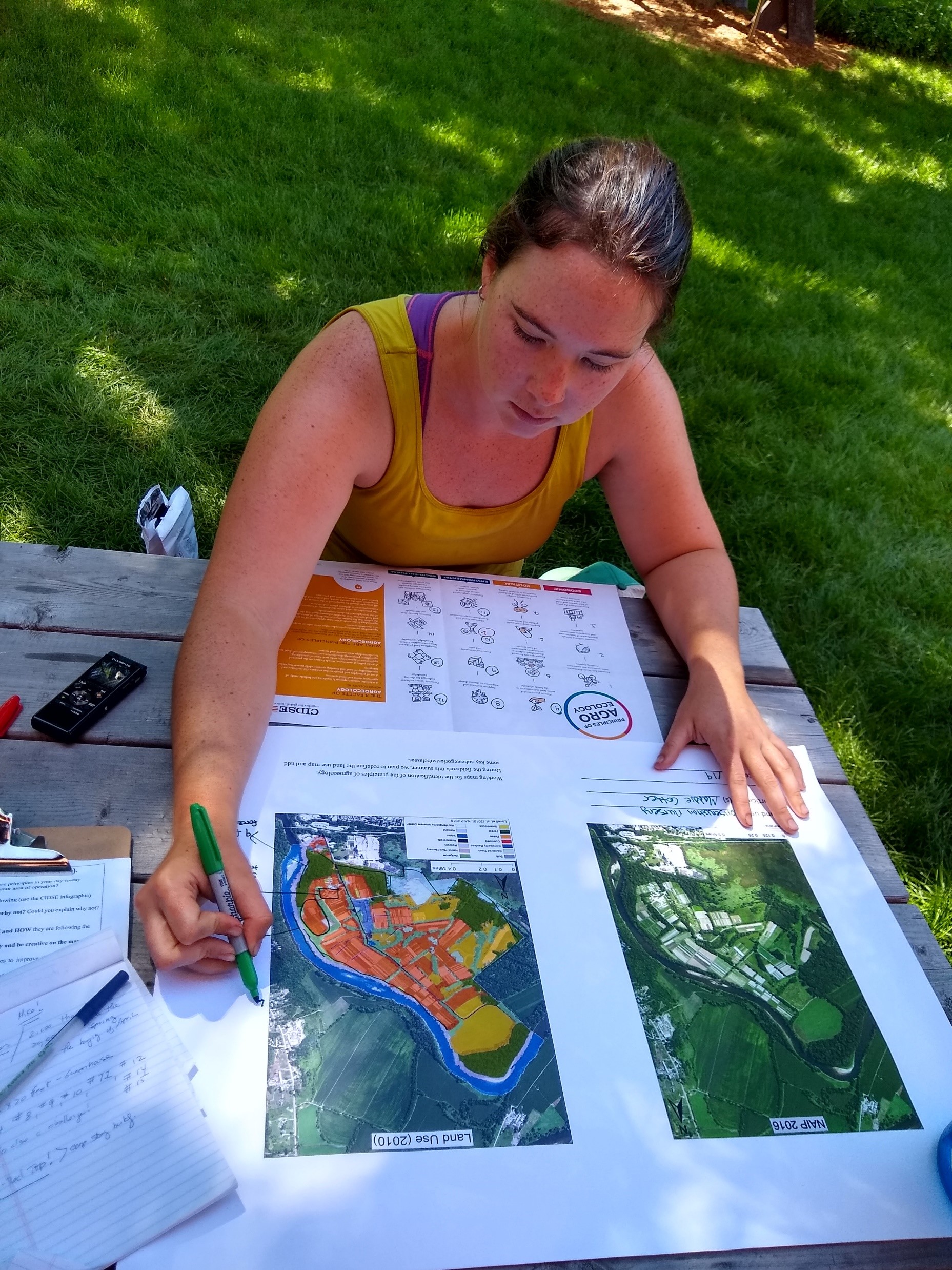

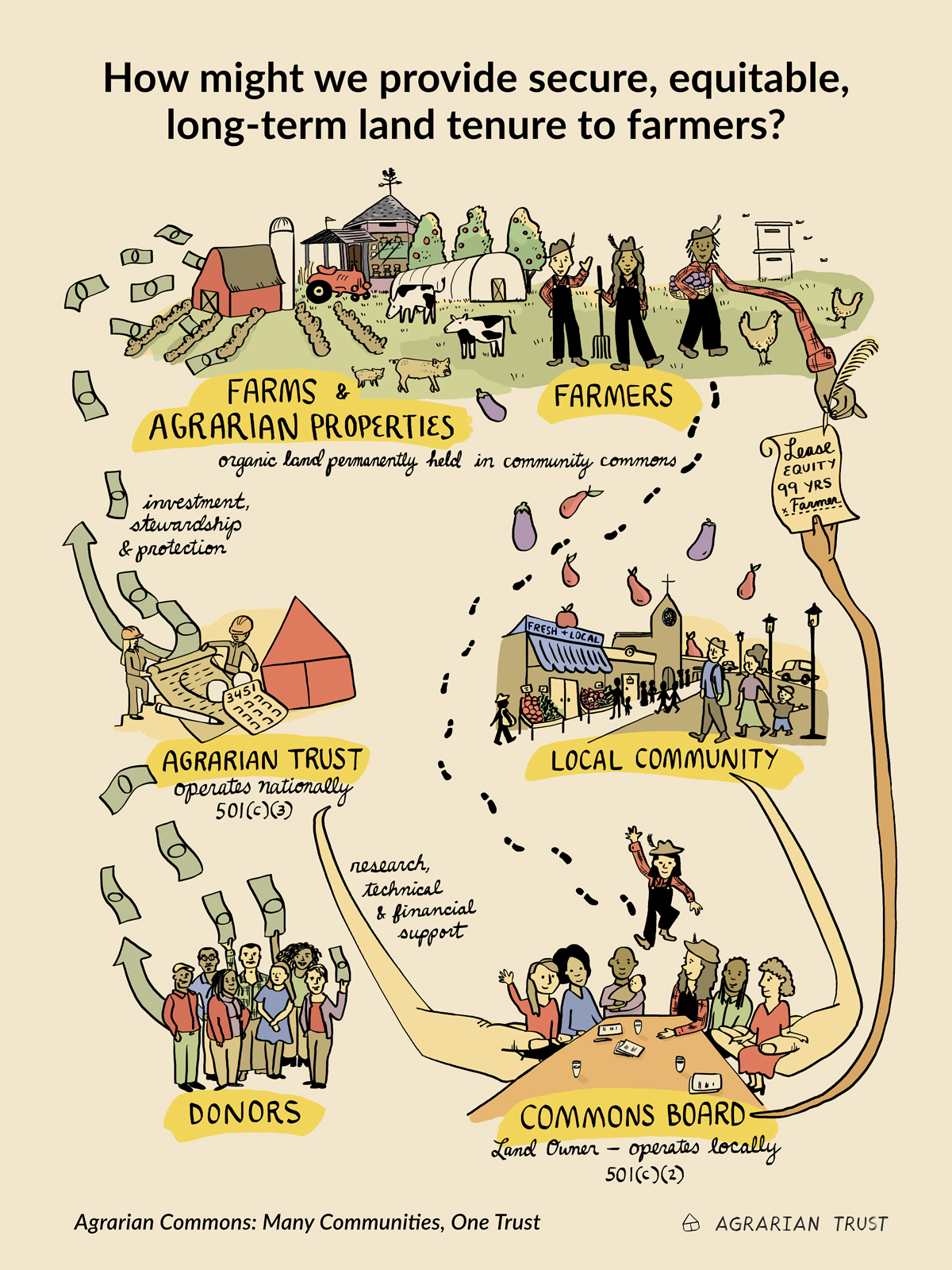

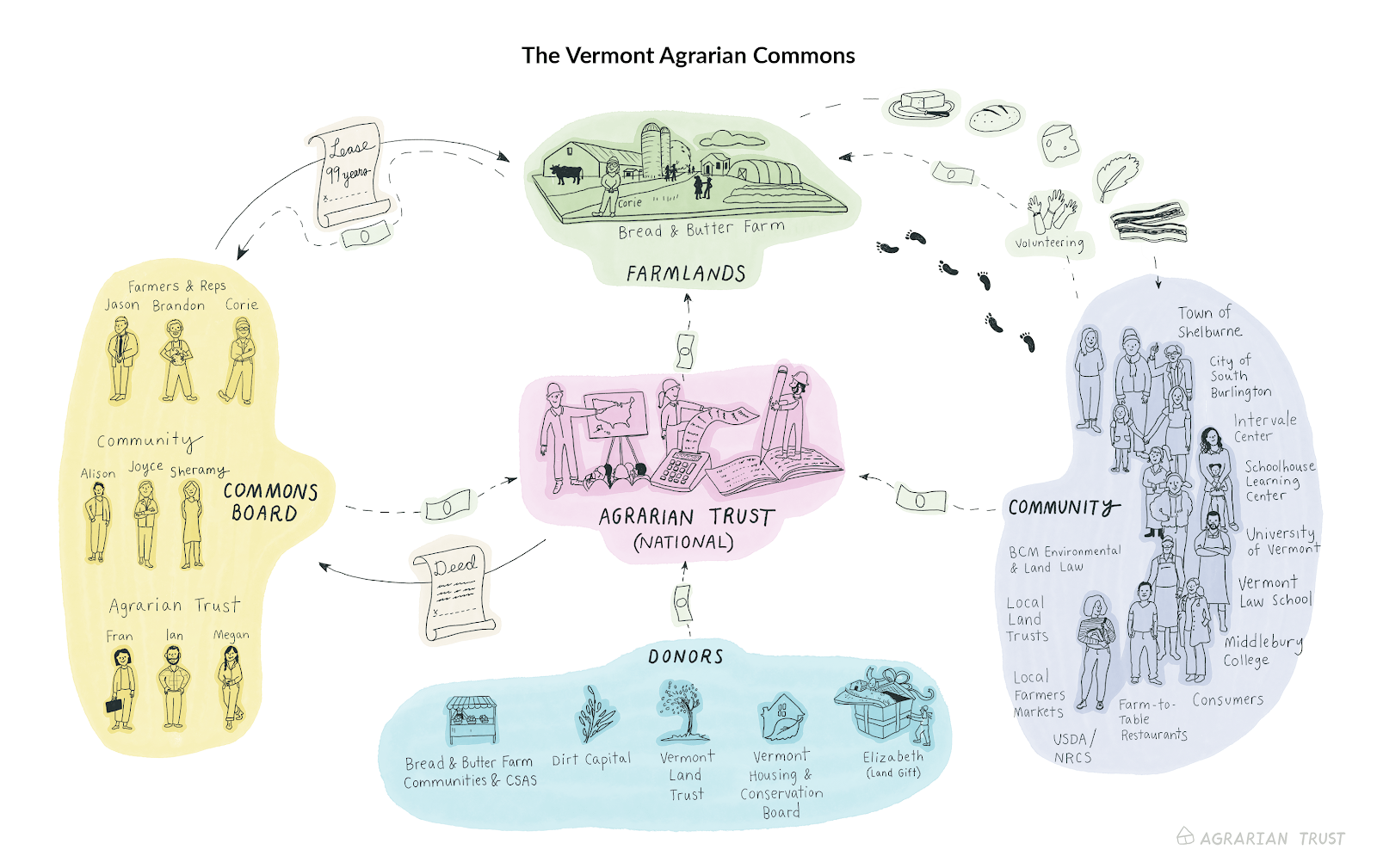

BLOG: Exploring the newly launched Vermont Agrarian Commons at Bread and Butter Farm

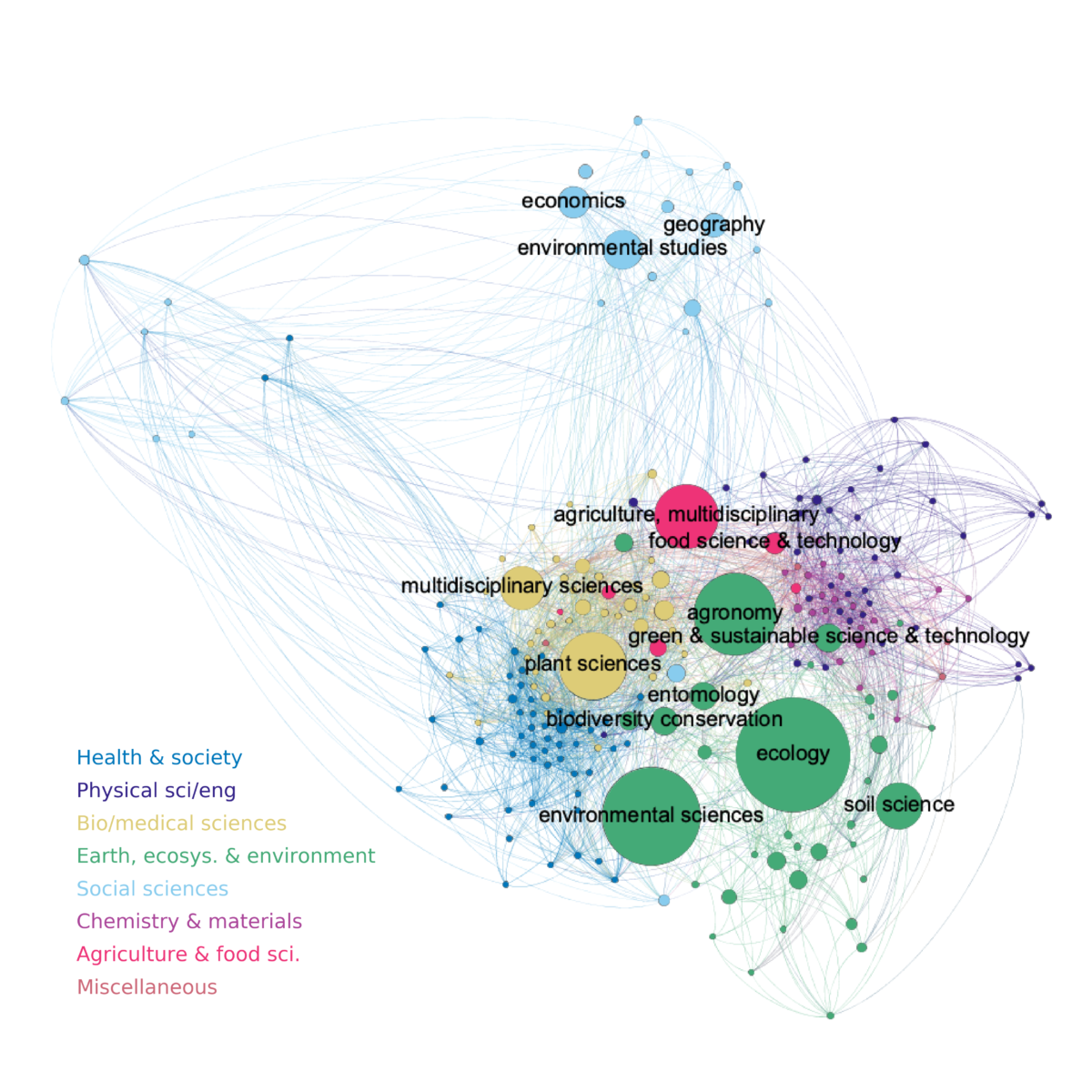

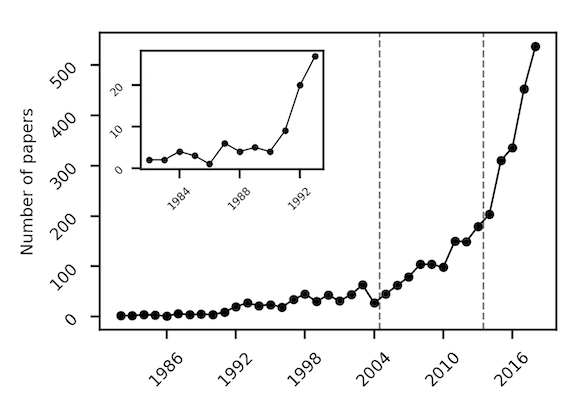

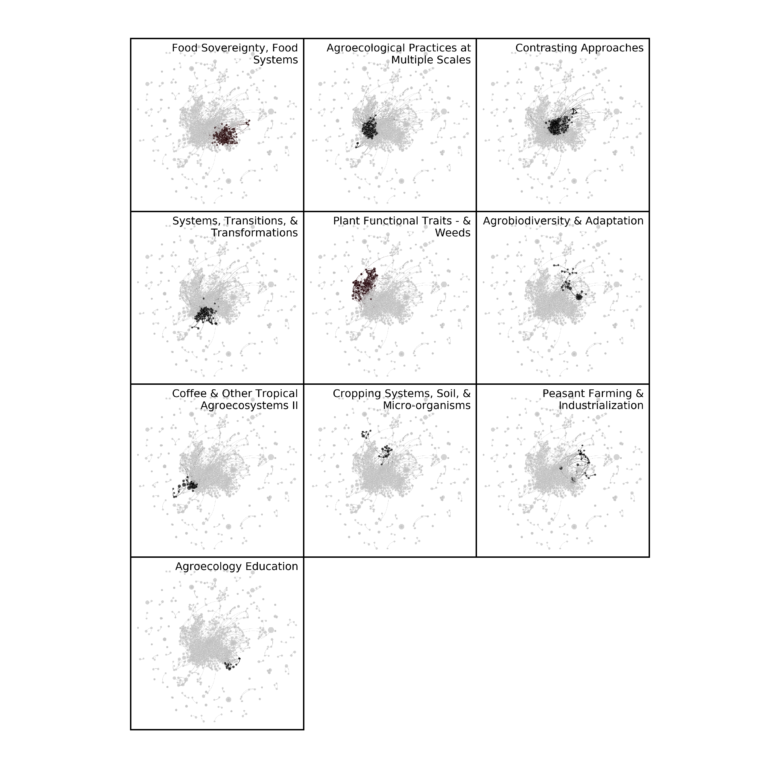

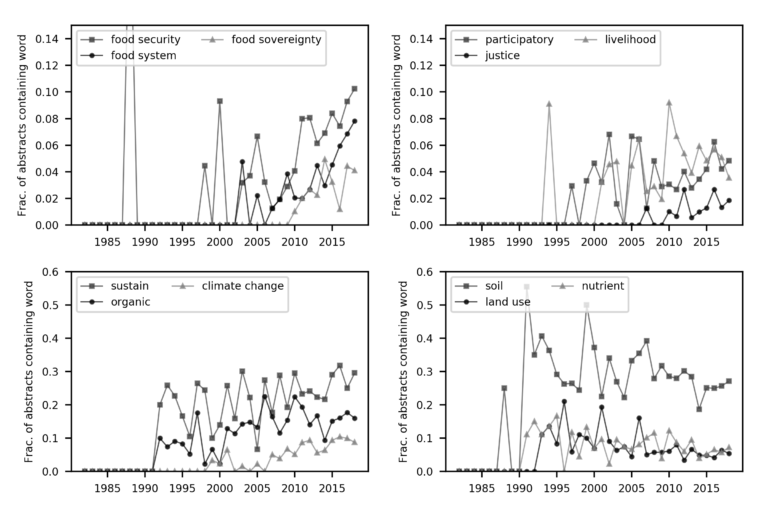

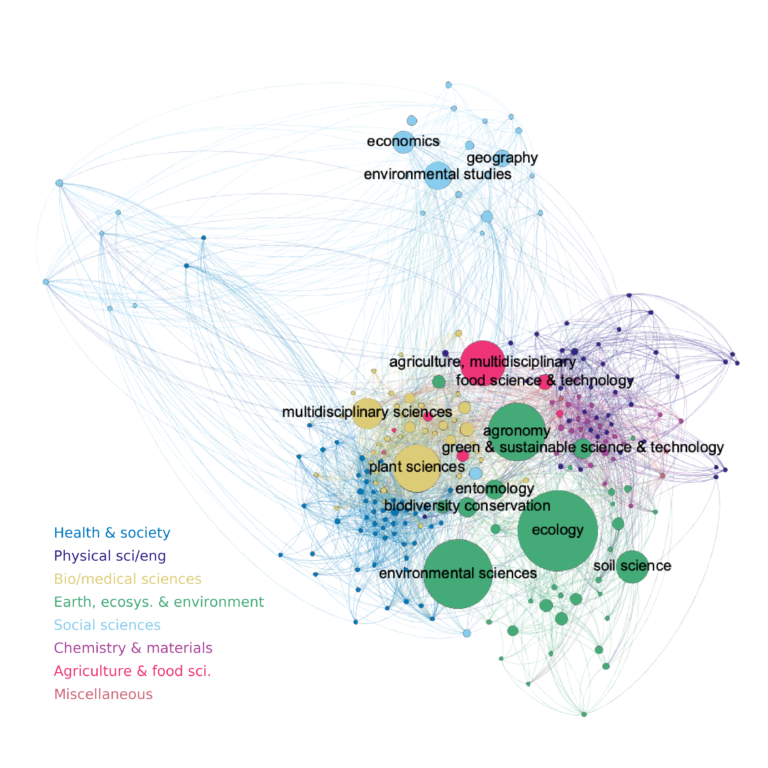

NEWS: ALC team contributes to important paper discussing ‘The evolving landscape of agroecological research’

NEWS: Highlighting ALC Co-director Ernesto Méndez on multiple panels

NEWS: Highlighting ALC Co-director Ernesto Méndez on multiple panels

ALC Co-director Ernesto Méndez has participated on three virtual events in the past month, one based out of the University of Vermont as well as two hosted by other institutions. See below for ways to access recorded versions. We are grateful for the opportunity to join in on important conversations, about food systems, agroecology and climate change, which are being held during such a critical time.

The evolution of agroecology as a practice, a research discipline, and a social movement – The UC Santa Cruz Center for Agroecology and Sustainable Food Systems, Quarterly Lecture Series

On October 7, Ernesto Méndez joined five experts in agroecology in giving ‘lightning talks’ on their interpretation of the evolution of agroecology as a practice, research discipline, and social movement. Recording coming here soon.

An evening with Jonathan Safran Foer, We are the Weather: Saving the Planet Begins at Breakfast – UVM Continuing and Distance Education, George D. Aiken Lecture Series

On October 8, Ernesto Méndez interviewed author Jonathan Safran Foer about his book, We are the Weather: Saving the Planet Begins at Breakfast, and work surrounding climate change. The event was heavily attended.

Dismantling and Rebuilding the Food System after COVID-19: The 5Ds – The University of British Columbia Centre for Sustainable Food Systems

On September 18, Méndez joined four other experts in the field to discuss redistributive policy tools towards the “5D of Redistribution”: Decolonization, Decarbonization, Diversification, Democratization, and Decommodification. Watch the recording here.

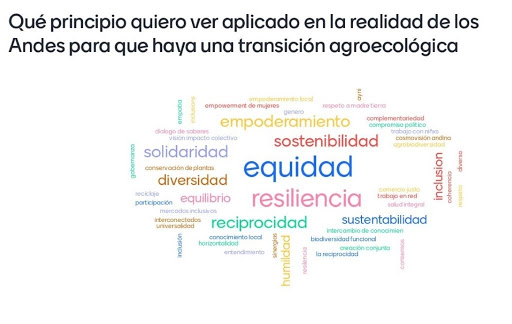

BLOG: In the vibrancy of the 16th annual meeting of the Andes Community of Practice / En la vivacidad de la 16ª reunión anual de la Comunidad de Práctica de los Andes

BLOG: Querencia y Comida: Nuevomexicanx Tradition as a Model for Food Resilience

NEWS: ALC member featured in Seven Days article on VT mutual aid

ALC member featured in Seven Days article on VT mutual aid

ALC graduate student, Sam Bliss, has been working tirelessly with Food Not Bombs for years. Their work, and that of many other VT organizations, are featured in this Seven Days article, highlighting their efforts since the onset of the COVID pandemic.

Member interview: Nils McCune on Puerto Rican coffee farmers, pandemic response and resilience, community building, and beyond

Put down your buzzer, this is not Jeopardy.

Put down your buzzer, this is not Jeopardy.

A blog reflecting on the COVID-19 pandemic by ALC Educational Coordinator Vic Izzo

Since the “Stay home, Stay safe” order was initiated here in Vermont, I have had the pleasure of spending each morning (and often evening) exploring the wonders of nature with my two year-old son. Our journeys are often a mixed bag. Some days we head out to a lesser-known hiking trail to learn about trees, while others days you might find us inspecting the entrances of ant nests poking out from the cracks in our driveway. Though these nature observations are fun and educational, my son’s most enjoyable outdoor excursions are our visits to our local community garden plots. Now don’t be presumptuous about my son’s predilection for gardening… While he does enjoy helping his dad turn soil, plant seeds, and water our thirsty seedlings, the real reason he begs for “garden time” is the resident woodchip, soil, and gravel “mountains” that he gets to climb unsupervised. With each successful ascent of these “mountains” he raises his arms in the air and begs for my adoration. These literal small victories are undeniably adorable; but more importantly, they have been a healthy reminder for me to appreciate those things around me…to smell the woodchips. To be honest, I barely noticed the many piles of sorted materials until my budding mountaineer scoped them out. I knew the piles were there but I never really acknowledged them or appreciated their significance. They are generally not on my radar and I’m not a two year old…

I recently had a similar revelatory experience during an intriguing ALC workshop led by a colleague from the Rubenstein School of Natural Resources, Dr. Matt Kolan. Matt is the director of the Leadership for Sustainability Master’s Program (MLS) here at UVM. His work and teaching uniquely examines leadership and education in a holistic and expansive way. Students in the MSLS program actively engage in discussions and projects that explore how power and privilege shape our educational and leadership experiences. During his lecture, Matt pointed out that the dominant model of higher education is built upon a process that selects for rapid and confident responders and rewards those students with positive descriptors such as “fast learner”, “quick processor”, or “confident speaker”. These designations are, of course, quite familiar to me as they are the backbone of many of my best recommendation letters. Never do I find myself writing that a student is a slow learner, moderate processor, or quiet communicator.

As I sat and listened to Matt’s reimagining of the college classroom, I found myself reliving some of my own undergraduate classroom experiences. Vividly I remembered how I approached each class as a contestant on Jeopardy, eagerly looking to prove my worth. From the moment I sat down in class, I was in a race to respond to any question or comment before my competitors could capture the instructor’s attention. In my mind, the entire lecture process was an opportunity to quicken my intellectual skills. Yet, as Matt and others within the workshop unpacked the pitfalls associated with selecting for rapid responders, I suddenly began to see a giant woodchip pile emerge from the periphery of my perspective. Similar to my son, Matt provided me with a new lens, or more precisely, he expanded my view of the world around me. He didn’t reveal anything necessarily complicated or new.Quite the contrary, he simply pointed out a rather intuitive concept: reactionary behavior is not always a beneficial trait.

Much the same way that our educational systems select for rapid responding students, our businesses, organizations and governmental agencies tend to seek out leaders that exhibit those same fast thinking and quick responding traits. Never has this tendency or bias been more evident than in the current COVID-19 reality. As the coronavirus pandemic has taken hold of our social, political and economic consciousness, so has the thirst for quick responses and reactionary policies. Daily news headlines and articles are chock full of economic timelines, infection rates, and critical examinations of decision making speed. From an academic perspective, I’ve seen no less than three recent grant requests-for-proposals (RFPs) with the word “rapid” in the title and an appropriately paired “rapid” submission deadline. Now, I acknowledge that crises, especially those of this magnitude, often necessitate quick decisions to avert catastrophe. However, it is important to acknowledge that the speed of a decision is rarely directly correlated with a successful outcome. As many of my fellow educators can attest, the rapid move to online instruction in response to the coronavirus outbreak, though (likely) necessary, may not have achieved the outcomes our organizations expected. Our communities are asking, begging leaders in every facet of society to make decisions, give us answers…now. And yet, when those quick decisions, predictions, and/or responses fail, we become angry, disappointed and (ironically) are often left at the trailhead of a longer road to resolution.

Witnessing and experiencing the pervasive pressure to make quick decisive decisions in my home and work life has left me depressed, frustrated, and introspective. It has also led me to more deeply consider the revelations brought to light by both my son and colleague:

Perhaps it is time to pause.

Perhaps it is time to slow down some of our decision-making processes.

Perhaps we need to call upon those “slow thinkers” to help us.

Perhaps there is a woodchip pile that we are not seeing that can provide us with a better vantage point.

Perhaps we should all take some time to think a little more like a two-year old.

Read Matt Kolan and Kaylynn Sullivan TwoTrees paper on the intersections of sustainability, diversity, privilege and power here.

ALC members attend 1st USFSA Political Education Course

ALC members attend 1st USFSA Political Education Course

By Martha Caswell, in collaboration with Nils McCune, Megan Browning, and Efren Lopez

In the days right before we were asked us to stay home, the US Food Sovereignty Alliance (USFSA) held their first national political educational course in Apopka, Florida. We were hosted by the Farmworker Association of Florida and the course was designed following a methodology of political formation developed in Latin America through the efforts of La Via Campesina (LVC) member organizations including the Brazilian Landless Workers’ Movement, Movimento dos Trabalhadores Rurais Sem Terra (MST), Organización Boricuá of Puerto Rico and the Asociación de Trabajadores del Campo (ATC) of Nicaragua, and others, which calls for an education of the mind, body and spirit. Participants came from the US, Puerto Rico, Mexico and Canada. Each drawn by the possibility of what we could create and learn by spending a week together focused on the history and future of food sovereignty in the US, and wanting to build a common political analysis of the food system that would lead us forward.

According to a 2018 publication from the European Coordination of La Via Campesina, food sovereignty is a ‘concept in action’ that “…offers itself as a process of building social movements and empowering peoples to organise their societies in ways that transcend the neoliberal vision of a world of commodities, markets and selfish economic actors. There is no one-size-fits-all solution to the myriad of complex problems we face in today’s world. Instead, Food Sovereignty is a process that adapts to the people and places where it is put in practice. Food Sovereignty means solidarity, not competition, and building a fairer world from the bottom up.”

So, there we were, nearly 40 of us – gathered in the cabins and grounds of a summer camp, to listen, learn, unlearn, and strategize. We came as farmers, activists, members of coalitions, and representatives of front-line organizations, each trusting that this was a critical step in our movement forward. Though neither of us was officially there representing the ALC, both Nils and I were there – Nils as a delegate of LVC and I on behalf of the Agroecology Research Action Collective. The ambitious agenda of the week left less time for individual connections than everyone hoped, but we covered a lot of ground, and uncovered/rediscovered a lot of truths. Our food system is broken. It has been built on a base of exploitation of land and peoples, and yet that narrative has been carefully and intentionally covered up. Our work is to interrogate both our past and present, to recognize where we are complicit and bravely face the discomfort of seeing ourselves in what is wrong. Only then, and through building solidarity with others, will we be able to achieve the transformation we seek. This blog from Agrarian Trust’s Megan Browning catches the essence of the week, https://agrariantrust.org/news/globalize-the-struggle-globalize-hope/

One of the closing observations of the event was that to make this transformation we will need revolutionary discipline and revolutionary healing. So, surround yourselves with good revolutionary people (even if only virtually), and follow Adrienne Marie Brown’s advice that joy is a form of resistance. Megan ends her post with a poem written by Efren Lopez, one of the incredible youth participants representing the Community Agroecology Network . I’ll do the same – it deserves more than one reading.

the tools that those frogs spoke about by the fire ~efren lopez

cool pools form on victory

missing the wet steps i took

from my casita to the library

it’s a foggy feeling, but

the warmth from the pier by the pond

it was part of the healing

the snap back raised my head

chin up! this fight isn’t a bed

back and calm and partially better

only then did i realize the weather

one huge storm!

from street to street

from coast to coast

from sea to sea

from pole to pole

one huge storm!

while our methods to bare

might reappear invisibly

i recall that other feeling

that hasn’t fleeted

explaining why we made the effort

to come together in the first place

because

it really takes a heart for the land

to understand

that the resistance to the forces

before us

the ones who hate our guts

calls us ruts

deprives our dignity

lack of pity

have no chance

when the seeds we sow

food we cultivate

has our hands not pointed

but loosely gripped

to the tools that we made

for each other

passing them to one another

circling our

collective battles

we sit

humbled

their resiliency

our resistance

in joy!

in joy!!

in joy!!!

New project launch: ALC takes on new grant from the McKnight Foundation

New project launch: ALC takes on new grant from the McKnight Foundation

The new cross-cutting Collaborative Crop Research Program (CCRP) grant – Agroecology Support to the CCRP, or AES, is in motion (as is its new official website!) The grant will be executed by a team from the University of Vermont’s Agroecology and Livelihoods Collaborative (ALC). The ALC, using its approach of transdisciplinary research and education and participatory agroecology, will work closely with teams from across the CCRP, and the three Communities of Practice (Andes, East & Southern Africa, West Africa), to deepen co-learning in agroecology, advance agroecological performance assessment and monitoring, coalesce support teams around agroecology, and engage diverse actors in a dialogue that advances agroecology globally. Read more about the team and their efforts here.

The COVID-19 Pandemic and Puerto Rico’s Food Sovereignty

The COVID-19 Pandemic and Puerto Rico’s Food Sovereignty

By Luis Alexis Rodríguez-Cruz

(ALC member Luis Alexis Rodríguez-Cruz recently published this Op-Ed piece in the Puerto Rican publication “El Nuevo Día.” It highlights the importance of food sovereignty during this moment of global crisis. Below is his translation of the article into English, which can also be found here. The original version in Spanish can be found here.)

Puerto Rican farmers and fisherfolks, beyond safeguarding our natural and agricultural resources, are key agents in strengthening our food security. Sadly, they have not been taken into account during the emergency we are going through. The COVID-19 pandemic should increase our awareness of our vulnerable island food security, and drive us to actualize actions that have a positive impact on our food system.

The Food and Agricultural Organization (FAO) of the United Nations highlights that food security is frail in island food systems. Given their small territories and economies, and higher exposure to extreme weather events, islands often do not have the resources needed to cope and recover quickly from impacts. Furthermore, their high dependence on imports is another obstacle towards achieving food security.

Puerto Rico imports around 85% of its food, and most of it is shipped from the port of Jacksonville in Florida. Moreover, the majority arrives at the port of San Juan. The escalation of the COVID-19 pandemic could heavily impact our supply chains. Thus, it is crucial that we have a strong local food system that can provide us a significant quantity of the food we need.

Before Hurricane Maria made landfall in 2017, our farmers and fisherfolks were seeing positive opportunities. Local production was increasing in a time of fiscal crisis. It was like we were slowly gaining awareness about the importance of food sovereignty. Puerto Rico, and its farmers and fisherfolks, need the power and control to produce the food that nourish us. Moreover, food sovereignty makes us aware of the political and power dynamics that govern our food systems. There cannot be food security without food sovereignty. We in Puerto Rico know very well what happened after Maria. Our food system is still recovering.

Farming in Puerto Rico is hard. Our farmers and fisherfolks, most of which are 50 or older, have to compete with cheap imports. They often do not have access to local markets, and the government does not facilitate them support to go through the bureaucracy the government itself imposes. Additionally, most of our farmers and fisherfolks are small-scale producers. They sell their products independently, through farmers’ markets, within their communities, and through small businesses. Though the curfew imposed by the governor of Puerto Rico does not apply to big producers, and wholesalers like supermarkets, it applies to street sellers, placeros, farmers’ markets, and other alternative venues. That negatively impacts farmers and fisherfolks.

The Secretary of Agriculture said this week that family markets will be canceled―an initiative that allow farmers to sell in municipal plazas to participants of the Nutritional Assistance Program―, and that he anticipates losses in local production. Furthermore, the media has reported improper police interventions with farmers (regarding the curfew), and with businesses important for farmers and fisherfolks’ to sell their products (e.g. restaurants). Yes, social distancing is crucial to decrease the spread of the coronavirus. But, did the governor took into account how the curfew would impact our farmers and fisherfolks? Was it considered how limiting local production would impact our food security, given our high dependence on imports?

As long as we continue to depend on supply chains that we cannot control due to the Jones Act and other federal and local measures, nor do we carry out policies that give political agency to our farmers and fisherfolks, our food system will not be prepared to feed us. We do not have the required food sovereignty to build a new food system that provide us the food security we deserve as islanders. If something the past disasters have taught us, through the political and bureaucratic pitfalls that our farmers and fisherfolks faced, is that we cannot reduce the vulnerability of our food system to a “production issue”. May this pandemic make us more aware of the importance of developing food sovereignty to feed ourselves.

VEPART featured on UNH Extension “Over-Informed on IPM” Podcast

VEPART featured on UNH Extension “Over-Informed on IPM” Podcast

The episode, called “PAR for Leek Moth” highlights our core team members, Vic Izzo (ALC Education Coordinator) and Scott Lewins (ALC Extension Coordinator), and their leek moth research project under the VEPART (Vermont Entomology and Participatory Action Research Team) umbrella. They detail issues the leek moth pest poses for farmers in the Northeast, control methods including Trichogramma wasps, the PAR (participatory action research) approach they take when working with farmers, and much more! Check it out here.

ALC hosts agricultural policy panel

ALC hosts agricultural policy panel

This week, we invited a host of inspiring actors in the food and agriculture scene here in Vermont to present on a panel in our weekly lab meeting.

Franklin County Conservation District

Franklin County Conservation District

Original art by Erok. Available on Rural Vermont website: https://www.ruralvermont.org/merch/art-cards-by-erok

NOFA-VT

Thank you to Elijah Massey of USDA – Rural Development, Grace Oedel of NOFA-VT, Graham Unangst-Rufenacht of Rural Vermont, and Jeannie Bartlett of the Franklin County Conservation District for providing insightful perspectives into agricultural policy work and the intersections of advocacy, food policy, farmer livelihood support, education, outreach, environmental stewardship, and beyond.

Our guests spoke to the collaborative nature of their work in that they are constantly sharing resources and co-creating the best ways to promote their programs and access producers and consumers across the state. This interconnectedness resonated with the ALC, a community of practice that also prioritizes collaboration and the co-creation of knowledge across disciplines and stakeholders.

We deepened the conversation about how to best strengthen collaborations between academia, research, and the work of organizations such as these. Calls were echoed among the group for continued applicable and participatory research and the development of meaningful scholar to non-profit/government entity linkages. We look forward to continued exchanges with these partners and others across Vermont.

Thank you all for the open dialogue and powerful momentum you all bring to this work!

Camilla was a participant in this years Introduction to Agroecology course (PSS 311), part of our

Camilla was a participant in this years Introduction to Agroecology course (PSS 311), part of our