In some of Alaska’s most far-flung villages, residents pay up to five times what other Americans pay for electricity. It’s carbon-heavy at every point in the process: diesel fuel, flown or barged in, is largely what powers the lights and heat in the Northwest Arctic Borough, where each village relies on its own electrical microgrid, unconnected to any larger utility network.

“Energy affordability is a real problem—people spend thousands of dollars a month on energy in a pretty extreme natural environment,” says Gund Faculty Fellow Mads Almassalkhi.

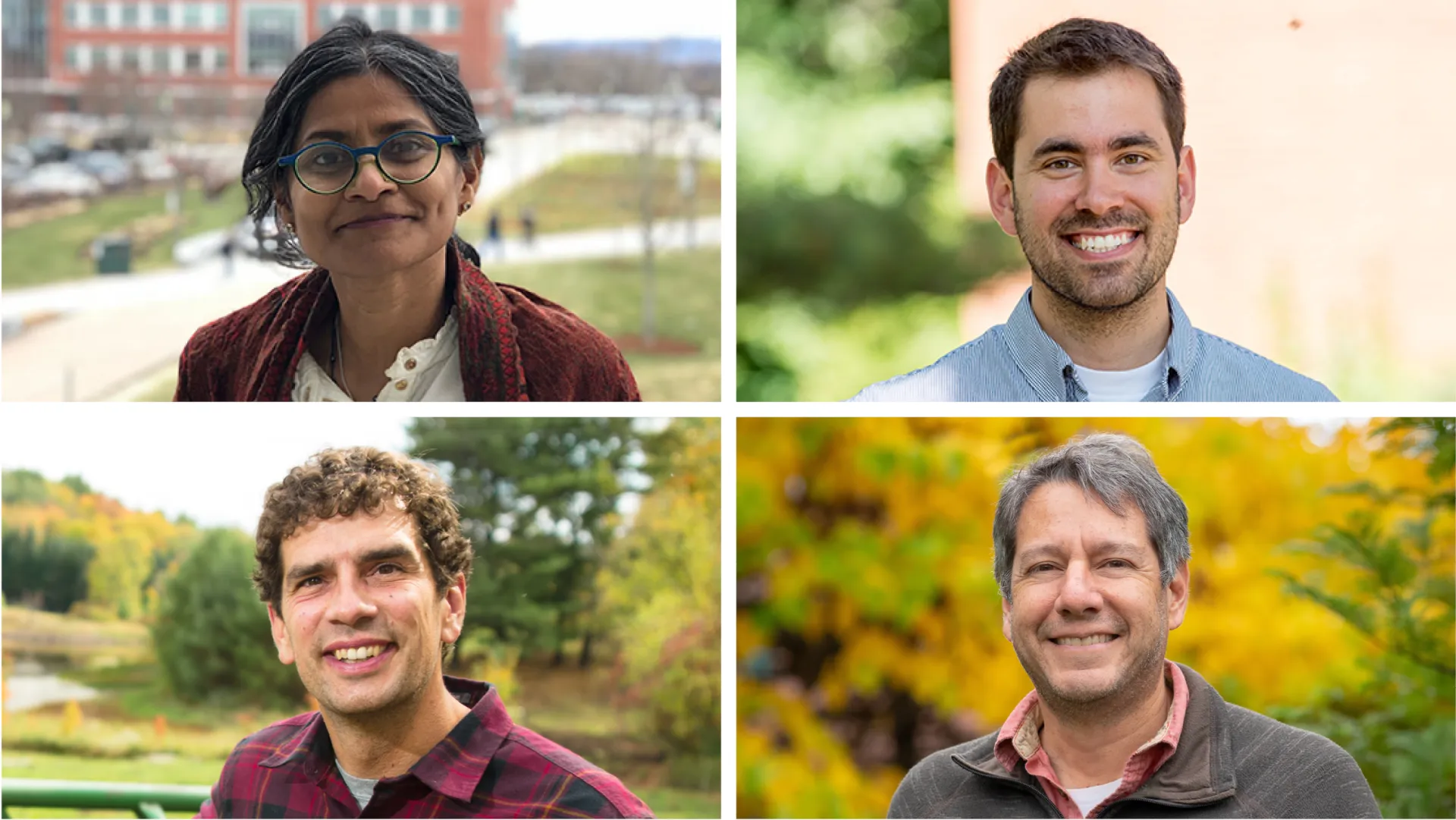

Almassalkhi is part of a team of UVM researchers who have for the past three years been working with local residents and organizations to investigate how to both bring down energy costs and reduce greenhouse gas emissions.

The project, which was originally funded with a Gund Institute Catalyst Award, now has partners from the University of Alaska, the Alaska Center for Power and Energy, Alaska Village Electric Cooperative, and Deerstone Consulting. It has also received grants from the Sloan Foundation and, recently, from the Northwest Arctic Borough.

'Trifecta Solution'

In January 2024, the UVM team, which also includes Gund Faculty Fellow Bindu Panikkar, brought on postdoctoral researcher Jayashree Rajaram Yadav, who has worked closely with local residents on the project.

Almassalkhi is based at UVM’s College of Engineering and Mathematical Sciences and leads the Center for Resilient Energy & Autonomous Technologies in Engineering (CREATE); Panikkar of the Rubenstein School of Environment and Natural Resources is looking into how renewable energy transitions are building energy sovereignty in the Arctic.

Both co-advised Yadav, a combined approach that was one of the project’s strengths, Almassalkhi says.

"We have a nice trifecta solution that combines social, economic and technical aspects,” he says. “We have Jayashree as this Rosetta Stone who serves to really translate between social research and technical engineering research.”

The epicenter of the work has been in the village of Shungnak, where the team has modeled potential energy-saving strategies to see if renewable energy sources could do the job, given the extreme conditions in this part of Alaska.

For example, heat pumps, often an alternative to fossil fuel heating systems, are highly efficient, but only up to a certain point, Yadav notes.

“Some technologies now available allow heat pumps to work down to -20 degrees C, and they are looking into those, but sometimes the temperature in this region goes below that as well,” she says.

“For now, they cannot go completely renewable; they need to have some diesel generation,” Yadav says.

Still, solar energy installation is easy, she adds, and in summer it provides enough energy that sometimes residents can turn off their diesel generators entirely. Wind energy remains an option through Alaska’s blustery winter nights, she adds.

The researchers say it was quickly clear that no single piece of this energy mix could meet the goals of keeping costs down, lowering carbon emissions, and remaining functional in Arctic winter conditions. The key was in looking at the tradeoffs, and combining several solutions. Could they work in concert?

Yadav’s models indicated that introducing a mix of energy-efficient heat pumps, solar photovoltaics, and wind energy into the village microgrid’s existing diesel-exclusive energy production would both lower costs and carbon emissions.

What's Next

Now, with the Catalyst project complete, the team is ready to move to the next stage. Yadav recently began a new role at UVM as a research associate, and with the recent funding from the Northwest Arctic Borough and the Department of Energy, she will explore how applicable what they’ve learned in Shungnak may be to other Arctic communities.

Meanwhile, based on recommendations from Yadav’s work on grid capacity, the local energy utility is in the process of purchasing transformers—covered by the federal grant—to accommodate the new heat pumps that will go to all the households in the region, Yadav says. She keeps an eye on real-time energy consumption in Shungnak, and the researchers anticipate receiving and sharing data as new systems go into use. Yadav is especially interested in gathering more data about the efficiency of combined solar and wind.

Yadav maintains her focus on the communities’ needs, knowing they, too, want to create a sustainable energy future.

“The local residents are very much interested in these kinds of discussions, talking about how they themselves can generate cleaner energy locally,” she says.