Technologies like artificial intelligence will be key for complying with a new EU law requiring companies to report on their impacts on biodiversity, and how biodiversity affects them. A new paper from various organizations including UVM’s Gund Institute for Environment outlines how and why scientists need to be involved.

The EU’s Corporate Sustainability Reporting Directive went into effect in early 2024, and, the authors say, about 50,000 companies—one-third of which are U.S.-based—are now wrangling with what its implementation will look like.

The law creates openings for novel, mutually beneficial working relationships between scientists and companies, coauthor and Gund Institute Director Taylor Ricketts says. Scientists need funding; companies need to gain a grasp on ecological information—things like changes in animal and plant populations—that is nearly universally outside their typical scope of work.

“Companies operating in the EU have to disclose what effects they have on biodiversity, and scientists know how to quantify that,” Ricketts says.

The new paper, published last month in the journal Conservation Letters, lays out suggestions for how and why scientists both should and must help companies comply with this new law.

Scientists' Skills

“(M)ost companies will need guidance on what data to collect and how to collect it, so that they can take action to halt and reverse nature decline,” the authors write. Scientists bring skills like accurately calculating change over time and determining cause and effect.

The work includes coauthors from Planet Labs, PBC, Microsoft, the Natural Capital Project, the Universities of Washington and Minnesota, and the Field Museum. This remarkably diverse set of collaborators came together to combine their expertise in biodiversity, data science, and policy to produce a 2024 white paper, which forms the basis of this peer-reviewed article.

Ricketts says one example that highlights the importance of tapping into scientific expertise to comply with this new regulation is the boom around data center construction. He explains that “scientists could survey all the species that are there—plants and birds and insects and frogs—before the site went in and then go back after the site was built to compare and measure the change.”

“That’s the key thing a scientist would ensure: that the company measures the change in the species based on what they’ve done,” Ricketts says.

He adds that by providing insight into which species are present in different potential building sites, scientists can also help companies make informed decisions in advance about where and how to build these centers with the least harm to biodiversity.

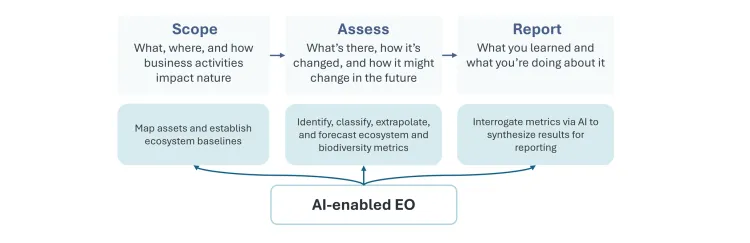

But with tens of thousands of companies now subject to the new directive, how can the needed data collection happen at both speed and scale? Earth observation technologies like remote sensing from satellites or drones, remote listening devices, and imaging technologies, can capture a snapshot of species present without the need for extensive fieldwork by a team of human researchers on the ground (though this more intensive work is also needed at times, Ricketts notes). Then, artificial intelligence can interpret images and soundscapes to identify which species are present, the authors say.

Of course, a company that makes soft drinks or provides financial services probably isn’t in the business of using AI to identify amphibians. Again, the authors say, enter the scientists, who, after guiding the data collection, also know how to use tools like AI to interpret the volume of data required in a shorter time.

“Part of the argument for companies to need to partner with us (scientists) is that there's no reason they should be expected to be biodiversity experts,” Ricketts says.

And, he says, such partnerships could unlock a new way to source and fund vast amounts of ecological data.

“Not only is this an opportunity to hold companies to account, but it could be a total bonanza for biodiversity sampling,” Ricketts says. “Companies could collectively create the world’s greatest ever database of species, where they are, how forests are doing, the conditions of wetlands.”