Greensboro Bend

Wildlife

The human-land relationship is deeply connected to wildlife. From watching backyard bird feeders and following winter tracks to fishing and hunting, daily life in Greensboro Bend involves wildlife.

With a set of focal species for Greensboro Bend, community members can maintain and improve their awareness of locally important species. Focal species were chosen based on the following factors: they are commonly found in Greensboro Bend’s natural community types, have habitat needs that are shared with those of many other species, are simple to identify by sight or sound, are culturally significant, and/or are in need of protection.

Upland Focal Species

Snowshoe Hare | Lepus americanus

Background

Single Cocoa Puff-like pellets—not in clumps like those of white-tailed deer—sprinkled along packed trails throughout your backyard woodlands are a sure sign of snowshoe hare presence in the wintertime. Shrubs or trees nipped at a 45-degree angle are also a telltale sign of this bounding beauty (white-tailed deer make a shredded end). Between the hazy glows of dusk and dawn, you may be lucky enough to see a flash of white among the greens and browns of conifers—fir, pine, and spruce.

Snowshoe hares undergo a significant transformation between October and December: molting to white. Come spring, they molt back to brown. This seasonal contrast gives the snowshoe hare the nickname “varying” hare. The snowshoe hare is often mistaken for a New England cottontail (Sylvilagus transitionalis) or eastern cottontail (Sylvilagus floridanus); its enormous hind feet (hence “snowshoe”) set it apart from the cottontails. The snowshoe hare would be a shoe-in champion of the hurdles events at the Olympics, as its long hind legs allow it to launch 12 feet forward in a single bound and travel up to 31 miles per hour.

Hares prefer conifer forests in mountainous areas. They rely on dense cover for protection from predators, such as bobcats, coyotes, fishers, foxes, and great horned owls. Snowshoe hares have a home range about the size of 16 football fields. In the summer, they feed on herbaceous plants like clover and ferns. In the winter, they feed on the twigs, bark, and buds of trees and shrubs such as balsam fir, mountain maple, raspberry, and speckled alder.

What You Can Do

The snowshoe hare is designated as a Vermont Mammal Species of Greatest Conservation Need (Medium Priority) in Vermont’s Wildlife Action Plan. There are steps you can take to familiarize yourself with and support this species.

- Take a field tracking workshop with The Green Mountain Club, Keeping Track, or North Branch Nature Center.

- Support snowshoe hare populations by providing cover, its top habitat need, through planting native species of shrubs and trees on your property. In this context, cover falls into two categories: 1) base cover and 2) travel cover. Base cover is comprised of dense conifers, where hares typically spend the day. Travel cover is also comprised of conifers, which enable hares to move from base cover to food sources.

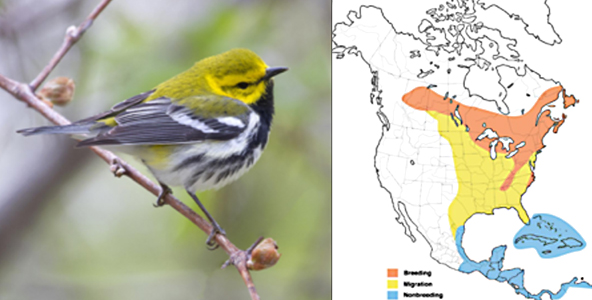

Black-throated Green Warbler | Dendroica vivens

Photo Credits | Left: Bryan Pfeiffer | Right: Cornell Lab of Ornithology

Background

Birders go gaga over warblers, a type of small songbird, because of their striking colors and beautiful songs. Warblers are like winged gemstones: blackburnian warblers, Canada warblers, and yellow warblers resemble citrine; black-throated blue warblers resemble sapphires; and black-throated green warblers resemble emeralds. In early spring, before our forests leaf out, eyes are peeled and ears are perked for these elusive sky gems.

The courting “uniform” of the male black-throated green warbler is fit for a fashion runway. He molts to breeding plumage (pictured above), a smattering of bright yellow-green contrasted against black and white—think bumble bee. He sends a five-note song, “zee-zee-zee-zoo-zee,” billowing from the tree tops to potential mates. The distinguishing characteristics of a black-throated green warbler are its black throat, yellow-green back, black and white “wing bars,” white belly, thick and straight black bill, and short tail.

Vermont is in the core of the black-throated green warbler’s breeding range (see range map above). It prefers continuous areas (~250+ acres) of closed forest canopy (>80% cover) in coniferous and mixed coniferous-deciduous forests. In boreal forests, which are present in the Greensboro area, it is strongly associated with red spruce. The black-throated green warbler typically nests in the fork of shrubs and saplings, 3-10 feet off of the ground. Its cup-shaped nest, mostly built by the female, would fit in the palm of a hand, and is made out of twigs, bark, and spider silk lined with feathers, hair, and moss. These birds are primarily insectivorous, feeding on non-hairy caterpillars as well as aphids, beetles, gnats, and spiders.

What You Can Do

Birds are significant indicators of ecosystem health. The Birder’s Dozen represents 12 of the 40 forest birds that the Audubon Vermont Forest Bird Initiative is working to protect. The black-throated green warbler is one of the Birder’s Dozen species present in Greensboro Bend.

- Learn to identify this bird by sight and or sound. When you’re out for a walk along Main Street or the Rail Trail in Greensboro Bend, listen for the two song types of the male black-throated green warbler. One song is used to court and communicate with females: “zee-zee-zee-zee-zoo-zee.” The other song is used to establish and defend territory among other males: “zoo-zee-zoo-zoo-zee.”

- Consider promoting natural conifer regeneration, especially on sites currently dominated by red maple (a result of heavy cutting of conifers in the past).

Wetland Focal Species

River Otter | Lontra canadensis

Photo credit Sean Beckett

Background

The river otter is the “cool aunt” of the weasel family; they are the most social and aquatic of the bunch. The weasel family is distinguished from other carnivorous mammals by its short legs, long body, and scent glands. Other members include the American marten, American mink, ermine, fisher, and long-tailed weasel.

Fish (trout, bass, and perch) are a staple of the river otter’s diet, as are crayfish, earthworms, frogs, insects, salamanders, and snakes. If you catch a pungent fishy smell riding the breeze along a bank, scan for a pile of fish scales; it’s likely river otter scat. They create “rolls,” zones of scat mixed with urine, to waterproof and spread the scent throughout their coats. River otters have scent glands on the soles of their feet and the area of the foot in between the toes and the ankle (metatarsal).

River otters are active throughout the day and year. Their home range varies from 1-22 square miles; to put that range into perspective, the distance from the headwaters of the Lamoille River at Horse Pond to the river’s intersection with East Main Street in East Hardwick is about 6.5 miles. River otters can cover a lot of ground! Their preferred habitat is the forested borders of streams, lakes, or other wetlands, where they den and play. River otters often seek out old beaver or muskrat dens as a homebase and create natural waterslides on banks.

What You Can Do

The river otter is designated as a Vermont Mammal Species of Greatest Conservation Need (Medium Priority) in Vermont’s Wildlife Action Plan.

- Consider land management decisions that maintain and improve the river otter’s preferred habitat, a complex structure of vegetation—dense herbs, shrub thickets, and fallen and submerged trees—along streams, lakes, and other wetlands. For example, sustain and enhance buffers along rivers, ideally 100 feet wide, on either side of the Lamoille River.

- Consider partnering with a land trust to conserve lands adjacent to the Lamoille River. Riparian networks in Greensboro Bend are locally and regionally important. Riparian networks, defined as lakes, rivers, streams, and ponds and their associated corridors, allow animals to travel along corridors to find suitable habitat. They also provide habitat for wildlife that heavily rely on riparian areas for survival, including beaver, mink, and river otter.

Aquatic Focal Species

Brook Trout | Salvelinus fontinalis

Photo Credit: VT Fish & Wildlife Department

Background

Brook trout are the kaleidoscopes of our rivers: vibrant shades of red, orange, and blue flickering in bold patterns. Their story is encapsulated in Greensboro’s cultural, recreational, and ecological values. The upland streams of the Lamoille River Watershed, which flow through Greensboro, supply cold water to the river mainstem. These small streams provide essential habitat for self-sustaining native brook trout, as well as blacknose and longnose dace, creek chubs, longnose suckers, and slimy sculpins. An angler’s dream!

Brook trout are Vermont’s smallest native species in the salmon family. They thrive in cool temperatures (32-65°F), well-oxygenated water, and a silt-free, sandy or gravel stream bottom. They primarily feed on aquatic insect larvae—stoneflies, mayflies, and caddisflies—and terrestrial insects, worms, leeches, and molluscs.

What You Can Do

Brook trout are designated as a Vermont Fish Species of Greatest Conservation Need (Medium Priority) in Vermont’s Wildlife Action Plan. Wild brook trout populations are sensitive to water pollution and habitat degradation, such as channel alterations and poor riparian vegetation. An influx of recreationists in Greensboro Bend will likely follow the impending construction of the “Morristown to Greensboro” section of the Lamoille Valley Rail Trail. In south Greensboro Bend, a portion of the west bank of the Lamoille River is managed by the Vermont Fish & Wildlife Department for the purpose of public access, specifically fishing.

- There is an opportunity for private landowners, the Fish & Wildlife Department, and a partnering organization, such as the Orleans County Natural Resources Conservation District, to work together on a restoration project that supports healthy rivers, healthy brook trout populations, and a healthy human community.

- Has it been a while since you went fishing? Want to learn how? Get outside with your family and friends and fish along the Lamoille River! You can buy a fishing license here. Let’s keep the habitat needs of this “brookie” beauty in check and its story alive for current and future generations to enjoy.

Both Upland & Wetland Focal Species

Fisher | Martes pennanti

Photo Credit: WA Department of Fish & Wildlife, John Jacobson

Background

The adaptable, generalist character of fishers is what makes them fascinating: they are agile in trees, on the ground, and in water bodies, and they’re opportunistic carnivores. A glance at the photo above tells you fishers are gosh darn adorable.

The fisher is a member of the weasel family, along with the American marten, American mink, ermine, long-tailed weasel, and river otter. Fishers prey on a medley of animals: birds, deer, mice, moles, muskrats, porcupines, shrews, snowshoe hares, squirrels (red, gray, flying), voles, and woodchucks. They also consume apples, berries, and nuts. If you think fishers have a smörgåsbord at their “fingertips,” you’re right! They are targets too: bobcats, coyotes, foxes, and great-horned owls prey on fishers.

Fishers are commonly found in both Lowland Spruce-Fir Forests and Northern Conifer Floodplain Forests (or Boreal Floodplain Forests), the predominant natural communities in Greensboro Bend. They prefer coniferous and mixed hardwood forests with continuous canopy cover; in the winter, the cover of mature conifers helps to keep their foraging energy costs low. Fishers den under large boulders, in hollow trees and logs, and in old porcupine dens.

What You Can Do

Forest blocks and wildlife connectivity blocks in Greensboro Bend are locally and regionally important. Forest blocks, defined as areas of contiguous forest that are unfragmented by roads, development, or agriculture, support ecological function, such as air and water quality and predator-prey relationships. Wildlife connectivity blocks are a network of forest blocks that provide terrestrial connectivity across Vermont, adjacent states, and Canada; they support the ability of wide-ranging animals to move across their range and supply suitable habitat for plants and animals in the face of climate change.

- Consider forest blocks and wildlife connectivity in town planning decisions, especially in developing areas. Maintain and improve a network of interconnected woodlands and keep potential denning sites, such as dead trees and logs, in mind, when making land management decisions.

- The more diversity in native vegetation, the better—it provides the habitat needs for fishers and their prey.

Ruffed Grouse | Bonasa umbellus

Photo Credit: VT Department of Fish & Wildlife

Background

Ruffed grouse are the masters of percussion and overwintering in our forests. Running into this explosive bird is like experiencing the clang of cymbals at a concert. Ruffed grouse can be flushed from their roosting sites on the ground, in trees, or in soft, deep snow. Similar to the sound of a distant shooting range, the rapid drumming of the males, most frequently heard at the time of snowmelt in spring through May, is created by compression waves from beating wings while the birds remain stationary. This love song and display, performed atop a downed log or stone wall, attracts females and fends off other males.

Ruffed grouse is one of two grouse species in the state; spruce grouse (Falcipennis canadensis) is the rarer of the two. The mottled brown, red, tan, and cream feathers of the ruffed grouse are the ultimate camouflage. This chicken-like game bird prefers brushy, mixed-aged woodlands and the presence of aspens and birches. Its ideal habitat is early successional—imagine a regenerating clear cut—or an abandoned apple orchard. In the winter, conifers provide cover and roosting sites. To make it through winter, the ruffed grouse employs several techniques: it plunges into fluffy snowbanks to stay warm on frigid nights, grows comb-like fringes on its toes to increase surface area and gripping ability, and gorges on shrub and tree buds. In addition to eating the buds of alder, aspen, birch, cherry, hazel, and hophornbeam, ruffed grouse feed on insects and the leafy vegetation of over 100 plant species.

What You Can Do

The ruffed grouse is designated as a Vermont Bird Species of Greatest Conservation Need (Medium Priority) in VVermont’s Wildlife Action Plan. The loss of habitat is the primary concern for the decline of bird populations. Aspens, both bigtooth and quaking, are the most important trees in the management of ruffed grouse. The good news: Greensboro Bend is chock full of aspen. Other forest types that are important in managing ruffed grouse are Red Maple-Northern White Cedar Swamps, Spruce-Fir Northern Hardwood Forests, Alder Swamps, and forests containing birch.

- Maintain and improve patches of conifers (¼-½ acre) for winter cover.

- Plant aspen and apple trees if they become less common.

Spotted Salamander | Ambystoma maculatum

Photo Credit: Sean Beckett

Background

We yearn for pops of color among the expanse of brown in spring: the purple-pink of hepatica, the red and yellow of red-winged blackbirds, and the yellow confetti on the backs of spotted salamanders. The spotted salamander is the largest of the three mole salamanders native to Vermont (the others are the blue-spotted salamander, Ambystoma laterale, and the Jefferson salamander, Ambystoma jeffersonianum). These salamanders spend a majority of the year overwintering in shrew, mouse, or mole tunnels, hence the name “mole” salamander. A 45-degree day paired with an evening rain precipitates a mass nocturnal migration. Salamanders mosey from their upland homes down to vernal pools, beaver ponds, and old farm ponds to reproduce. One individual may trek to the same body of water up to 20 times in its lifetime.

The spotted salamander prefers moist deciduous or mixed woods in or next to floodplains, streambanks, and rocky hillsides; it seeks shelter beneath rocks, logs, stumps, and boards. For breeding, it needs permanent, semi-permanent, or ephemeral water without fish. The adult spotted salamander’s diet consists of earthworms, snails, slugs, spiders, and insects, especially larval and adult beetles.

What You Can Do

The spotted salamander is designated as a Vermont Amphibian & Reptile Species of Greatest Conservation Need (Medium Priority) in Vermont’s Wildlife Action Plan. Although this salamander is widely distributed across Vermont, it is a medium priority species because of the high number of deaths that occur as they cross roads to and from breeding pools.

- Why did the salamander cross the road? Get outside to find out and help out! Volunteer with the Vermont Vernal Pool Monitoring Project through the Vermont Center for Ecostudies or the Amphibian Road Crossing Program at North Branch Nature Center.

- If you have a vernal pool on your property and harvest timber, consider following the Vermont Center for Ecostudies Suggested Guidelines for Timber Harvesting Around Vernal Pools (PDF).

Monarch Butterfly | Danaus plexippus

Photo Credit: Bryan Pfeiffer

Background

The sight of the first monarch flitting across a summer sky inspires a jump for joy. The monarchs arriving in our fields between June and August are the third or fourth generation of an annual mass migration. Imagine an epic relay, where participants are in pursuit of the prized gold medal: milkweed. The first generation migrates south to overwinter in mountainous central Mexico; the second generation begins the return flight to the northeast, but doesn’t make it the whole way; the third or fourth generation completes the relay, landing in the fields of New England to lay eggs. A monarch can travel 40 to 100 miles per day. From egg, to caterpillar, to golden-speckled chrysalis, to adult, monarchs are in constant training for a great migration.

Yellow-orange and purple-pink are the royal colors of the monarch and the plants it relies on. These colors are from the palette of an accomplished artist. Monarch caterpillars specialize on common milkweed (Asclepias syriaca), showy milkweed (Asclepias speciosa), and swamp milkweed (Asclepias incarnata). The adults are generalists and feed on the nectar of a range of plants, such as New England American-aster (Symphyotrichum novae-angliae), pictured above, purple Joe-Pye weed (Eutrochium purpureum), and eastern purple coneflower (Echinacea purpurea). These butterflies prefer open meadows, weedy areas, marshes, roadsides, and disturbed habitats with milkweed. The monarch is Vermont’s official state butterfly! The viceroy butterfly (Limenitis archippus) is a Mullerian mimic of the monarch, meaning it has similar coloration. The viceroy is smaller than the monarch and has a distinct black band across its hind wings.

What You Can Do

The monarch butterfly is designated as a Vermont Invertebrate Species of Greatest Conservation Need, Butterflies-Grassland Group (High Priority) in Vermont’s Wildlife Action Plan due to habitat loss, especially of its host plant, milkweed.

- Help provide habitat for monarchs by planting milkweed in your yard, home garden, school garden, and community park, and along sidewalks and trails. Not only is milkweed beautiful, but it also creates a wonderful opportunity to learn the lifecycle of this magical creature, the monarch.

Works Consulted

All About Birds: The Cornell Lab of Ornithology. (2019). Retrieved from https://www.allaboutbirds.org/.

Audubon Vermont. (2019). Retrieved from http://vt.audubon.org/.

Bryan, R.R. (2007). Focus Species Forestry: A Guide to Integrating Timber and Biodiversity Management in Maine. Falmouth, ME: Maine Audubon.

Crossman, E.J., & Scott, W.B. (1975). Freshwater Fishes of Canada. Ottawa, CA: Fisheries Research Board of Canada.

Degraaf, R.M., & Yamasaki, M. (2001). New England Wildlife: Habitat, Natural History, and Distribution. Hanover, NH: University Press of New England.

Hagenbuch, S., Manaras, K., Shallow, J., Sharpless, K., and Snyder, M. (2011). Birds with Silviculture in Mind: Birder’s Dozen Pocket Guide for Vermont Foresters. Huntington and Waterbury, VT: Audubon Vermont and the Vermont Department of Forests, Parks, and Recreation.

Holland, M. (2010). Naturally Curious: A Photographic Field Guide and Month-by-Month Journey through the Fields, Woods, and Marshes of New England. North Pomfret, VT: Trafalgar Square Books.

Kostyal, K.M. (2010). Great Migrations. Washington D.C.: National Geographic Society.

Lamoille River Basin: Water Quality Management Plan. (2009). Waterbury, VT: Agency of Natural Resources, Department of Environmental Conservation, Water Quality Division.

Sorenson, E.R., & Zaino, B. (2018). Vermont Conservation Design: Maintaining and Enhancing an Ecologically Functional Landscape. Vermont Fish and Wildlife Department, Vermont Agency of Natural Resources.

Thompson, E.H., & Sorenson, E.R. (2000). Wetland, Woodland, Wildland: A Guide to the Natural Communities of Vermont. Hanover, NH: University Press of New England.

Vermont Center for Ecostudies, Vermont Atlas of Life. (2019). Retrieved from https://vtecostudies.org/projects/vermont-atlas-of-life/.

Vermont Fish & Wildlife Department. (2019). Retrieved from https://vtfishandwildlife.com/learn-more/vermont-critters.

Vermont Reptile and Amphibian Atlas. (2019). Retrieved from https://www.vtherpatlas.org/.

Vermont Wildlife Action Plan Team. (2015). Vermont Wildlife Action Plan. Vermont Fish & Wildlife Department. Montpelier, VT. Retrieved from http://www.vtfishandwildlife.com.

Werner, R.G. (1980). Freshwater Fishes of New York State. Syracuse, NY: Syracuse University Press.