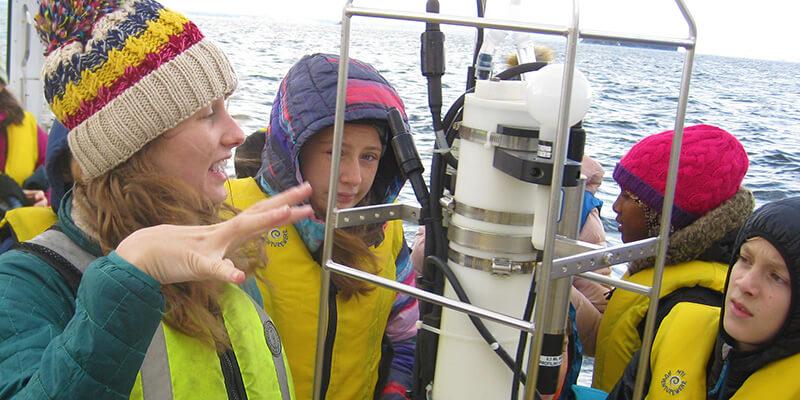

Out on Lake Champlain on a brisk October morning aboard the University of Vermont’s research vessel Melosira, Rubenstein School of Environment and Natural Resources student Kat Lewis ’19 is exploring ecology with 21 bundled-up Burlington middle schoolers.

Lewis, an environmental sciences major, is one of eight Rubenstein School students who are paid watershed educators in UVM Extension Watershed Alliance, part of the Lake Champlain Sea Grant program. She’s telling the seventh and eighth graders from Edmunds Middle School that the ratio of land in the Champlain Basin to water in the lake is 18 to 1.

“So thinking about how there’s such a large amount of land draining into Lake Champlain,” Lewis says, raising her voice above the wind, “what do you think some of the issues are?”

“There’s a lot of runoff, like from farms,” one student volunteers.

“And there’s pesticides,” offers another.

Lewis agrees — and moments later, the students are grabbing waterproof clipboards and markers and making notes on the weather, the geography around them, and the water clarity below. Guiding them together with Lewis is Ashley Eaton, the watershed and lake education coordinator for Lake Champlain Sea Grant, a cooperative program of the university and the State University of New York at Plattsburgh, with UVM Extension as a key partner.

Lake Champlain Sea Grant develops and shares science-based knowledge to benefit the communities and economies of the Champlain Basin. As part of a network of 33 Sea Grant programs in important coastal areas around the country, it uses federal and state funding to blend research, education, and outreach in a variety of ongoing projects.

Through Watershed Alliance, elementary, middle and high school students and teachers up and down the Champlain basin are guided by watershed educators — all of them UVM undergrads, nearly all from the Rubenstein School — through hands-on stream monitoring and lake sampling, plus fish assessment in the waterfront Rubenstein Ecosystem Science Laboratory.

“We teach the watershed educators everything they need to know, which is part of what makes it such a cool experience,” Eaton says. After receiving 20 hours of intensive training, each watershed educator spends 50 to 75 paid hours during the semester working with school groups. The program also offers K-12 teacher trainings in the summertime.

“When I found this, I knew I needed to be a watershed educator,” says Kat Lewis, who has watched the water quality deteriorate in a New Hampshire lake her family visits in the summer. “It’s teaching the next generation how to conserve their water and improve water quality. Because I’ve seen what’s happening.”

“What Can We Do?”

Improving Lake Champlain’s water quality is an urgent priority of both scientists and public officials — and several other Sea Grant projects aim to make a direct positive impact on the lake. Coordinating some of those efforts is Kristine Stepenuck, Ph.D., a Rubenstein School assistant professor who is the UVM Extension leader for Sea Grant.

Working actively with a number of Rubenstein School undergraduate and graduate students, Stepenuck is leading three current projects:

- Helping municipalities and private contractors learn how they can use less salt while still keeping roads, driveways, and parking lots ice-free during the winter.

- Encouraging homeowners to cut their grass no shorter than three inches, through the Lake Champlain Basin Program’s Raise the Blade initiative. Not cutting lawns too short allows their root systems to grow stronger, absorbing more water that would otherwise run off.

- Making it easier for recreational boaters on Lake Champlain to use marina pump-out stations to empty their waste tanks.

The question that runs through all these projects, Stepenuck says, “Is what’s your individual opportunity to help improve water quality? What can we do?”

Supported by both federal and state funding, Lake Champlain Sea Grant is guided by an advisory committee of stakeholders from throughout the watershed. “They help us focus in and determine our direction,” Stepenuck says.

“With the different projects we’re working on, there’s a lot of research, outreach, and coordination to be done,” she adds — “and the Rubenstein School students really increase our capacity to do this work.”

Before they went out on the Melosira, the Edmunds middle schoolers worked with Kat Lewis and other watershed educators to investigate Potash Brook, near their downtown school. At three locations — up-, mid- and downstream — they tested for water quality and sediment pollution.

“We looked for benthic bottom-dwelling creatures,” says Amos Lilly, grade 7. Those aquatic macroinvertebrates live in streams, he explains, and are water quality indicators.

“If you find them, you can tell the stream’s not polluted,” adds eighth grader Jasper Martinez. “Because if it was, they couldn’t breathe.”