New Haven

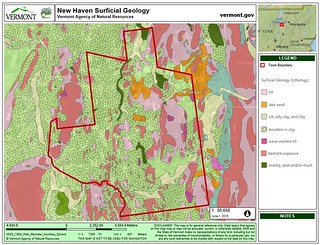

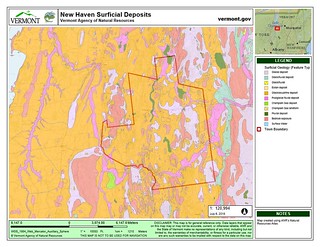

Surficial Geology

Written by Emma Stuhl

Surficial geology describes the layers of sediments that lie over the bedrock, but under the living soil where plant roots, fungi, and invertebrates live and grow. While much of the land in Vermont has at least one layer of surficial deposits, some living soil lies directly upon bedrock.

An artist’s rendition of the last glacial maximum. “IceAgeEarth” by Ittiz - Own work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Commons

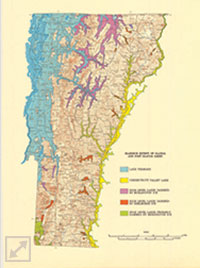

An artist’s rendition of the last glacial maximum. “IceAgeEarth” by Ittiz - Own work. Licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via CommonsIn the Champlain Valley, as the glacier melted and retreated, the solid ice blocked the northern outlet for the valley’s water. Since the melting ice sheet released enormous quantities of water, the dammed valley filled with water to a much higher level than current day Lake Champlain, creating what geologists call Lake Vermont (see Vermont Geological Survey image below). The surface of Lake Vermont was 500 feet higher than Lake Champlain today, and covered much of modern-day New Haven.

Lake Vermont was a murky lake, as the rivers that flowed into the lake carried lots of loose sediment from the scoured hillsides and from the glacier itself. At the river mouths, as the water slowed, the relatively heavy sand particles fell out of the water column and formed sandy delta deposits and beaches at the water’s edge. As the water flowed into the lake, finer silt and clay sediments settled to the bottom of the lake. Glacial Lake Vermont covered the Champlain Valley for over a thousand years, collecting substantial clay deposits that later gave rise to the clay and loam soils that are common in New Haven today.

About 12,000 years ago, the ice dam broke. Lake Vermont abruptly drained, reducing the water level by 300 feet in hours or days. This rapid change in water level exposed the clay that had settled to the bottom of Lake Vermont in New Haven, paving the way for the vegetation that eventually colonized the post-glacial landscape.