Professor Paul Kindstedt simply aimed to write a textbook for his nutrition and food science students at the University of Vermont.

But in 2003, when he was in the thick of writing American Farmstead Cheese: The Complete Guide to Making and Selling Artisan Cheeses, he knew he need a little historical context to help new farmstead cheesemakers today understand the big picture. But Kindsted easily realized that the 9,000-year history of cheese was, well, it's another story. He knew there was an important story to tell, one that would connect today’s traditional cheesemakers with their ancient roots, but it would require much deeper research.

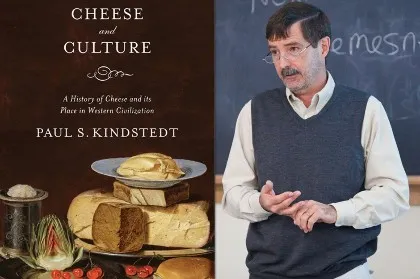

Nine years and more than 250 pages later he tells that story in the recently published, Cheese and Culture: A History of Cheese and its Place in Western Civilization. This big cheese bible is not only a textbook, but a rich backgrounder for cheese aficionados, handbook for cheesemakers, lens through which to understand history and "worth your time," according to critics such as "The Atlantic" magazine.

Kindstedt's expertise is, according to his curriculum vitae, in the technology of cheesemaking physicochemical and biochemical processes that influence the functional characteristics of mozzarella. He built his career helping large industrial cheese producers perfect their products for a mass market.

But Kindstedt began to change course in 2005 with the publication of American Farmstead Cheese and his role as co-director of UVM's Vermont Institute of Artisan Cheese.

Helping small producers flourish became the rationale for following a trail of sometimes obscure references to cheese in art, religion, literature, classics, archeochemistry, archeoclimatology and more.… areas both foreign and thrilling to Kindstedt. Wherever a specialist in one of these areas made a passing reference to cheese, the scientist, looking through “a different set of eyes,” found a piece of his complex puzzle (“Whoa, that’s global climate change shifting the whole direction of cheesemaking in Europe!” he said, as an example). Eventually, painstakingly he built, for instance, the first comprehensive narrative of when, how and why hard sheep pecorino cheese was developed in one region and soft-ripened cow’s milk cheeses in another.

Kindstedt tells the reader how the landscape, the climate, the economy, the politics shaped the cheese and, equally so, how cheese came to shape the cultural identity of the people and the place where it’s made. It’s not an understatement, Kindstedt says: “Cheese helped shaped everything in terms of who we are.”

Like Salt: A World History, Spice: The History of a Temptation, Cod: A Biography of the Fish that Changed the World, and several other comprehensive nonfiction history books on the likes of sugar, chocolate and even the banana, published since the new milennium, Cheese and Culture postulates that this food changed the course of history.

Molding tradition

Kindstedt's tale of cheesemaking began around 7000 B.C. as devastating overuse of land in the once Fertile Crescent of western Asia began to be used for grazing ruminant animals instead of growing crops. The advent of pottery allowed for collecting milk combined with the realization that adults (then universally lactose intolerant) could consume dairy foods if coagulated and the whey was drawn off — cheese became a food staple.

Jumping forward several millennia, Kindstedt argues that the Roman Empire lasted 500 years, at least in part, because Romans were accomplished cheesemakers. “The reason why they were able to hold these vast areas,” he says, “is because when they set up a fort or new province they immediately established an agricultural installation. They took the technology of sheep milk cheesemaking — and wool production for blankets and clothing — and made that the basis of a military provisioning network that enabled them to permanently station a half million troops on a 10,000-mile border.”

A favorite example of Kindstedt’s that gets to the synergy between the place and the cheese is the rugged alpine cheeses of central Europe. That story begins around the start of the fourth millennium B.C. when there was a dramatic global climate shift that led to long, severe winters and warmer wetter summers in this part of Europe, wreaking havoc on the Neolithic peoples huddled in the river valleys along the Danube and the Rhine, most of the land being too heavily forested to cultivate crops or graze animals. But over the long term, the extreme cold caused forestlands to thin, enabling people to move to higher ground, clear and cultivate fields. It also caused tree lines to recede down alpine slopes as much as a thousand vertical feet. By 2500 B.C. there’s evidence of people moving animals up the mountaintops to graze in the summer, turning their milk into hard cheese to stockpile for the winter while cultivating crops below.

What began, then, as a survival strategy became an embedded part of the culture in many parts of Austria and Switzerland. “It persists to this day,” says Kindstedt, “because it’s part of local life, part of local identity. The movement of the animals up in the spring becomes this enormous cultural celebration — when they come back down there’s another celebration. It’s part of the identity of the people themselves.”

Kindstedt believes that Americans have historically missed out on this deep connection between place and food that is demonstrated throughout the pages of his book, Cheese and Culture. “Those traditional technologies that did arrive (in America) from Europe were changed as the cheese industry changed,” he says. Americans’ lack of a shared identity around food, Kindstedt believes, is due to its relentlessly mobile society in contrast to Europe, where people have commonly lived and died in the same place where their great grandparents did. “We’re always moving,” he says. “Culture is shared collective experience over time."

The immense popularity and award-winning international respect of small-batch farmstead cheeses, especially from Vermont; the success of the nation's only center for teaching and research on farmstead cheeses — UVM's Vermont Institute of Artisan Cheese; and the prestigious acclaim of Paul Kindstedt's Cheese and Culture: A History of Cheese and its Place in Western Civilization, a story told with the precision of a scientist and the devotion of a cheese connoisseur; are all signs that the tide of American food culture may be turning. And not a moment too soon.

~LeeAnn Cox and Cheryl Dorschner contributed to this article.