University of Vermont boasts a unique land-grant legacy. Justin Morrill, a Vermonter, was the legislator who wrote and sponsored the Morrill Act of 1862, which gave federal lands to states to establish colleges for science and agricultural education. That bill, which Abraham Lincoln signed into law, paved the way for the majority of today’s agricultural education. Generations of farmers have studied at land-grant institutions around the country, many of them following in their family's footsteps to learn the latest technical knowledge so that they can continue their family farms. Terry Bradshaw attended UVM, Vermont’s only Land Grant University, in the 1990s. He grew up on a Vermont farm, and when he arrived at UVM, he already had the practical know-how of farming; what he lacked was scientific knowledge about agriculture.

“I got my undergraduate degree here in Plant and Soil Science. That was the name of the degree, and we had concentrations within that degree. The majors were called ‘Sustainable Agriculture’, or ‘Urban Forestry and Landscape Horticulture’. The basic distinction was, ‘Do you eat the plants, or do you look at the plants?’”

Agriculture

Bradshaw is in a unique position today to observe students attending UVM, as he currently chairs that same program, renamed this month to become the Department of Agriculture, Landscape, and Environment (formerly Plant and Soil Science). He oversees its current 100 or so undergraduates, as well as a dozen graduate students, and is also responsible for managing one of the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences (CALS) working farms, the Horticultural Education and Research Center in South Burlington. Enrollment in these programs have increased 137% since 2020.

“In most Land Grant Universities Ag programs, you will have people who already know farming; they know the basics. They can drive a tractor and have been since they were ten. They need to learn agronomy and about soils, and we still teach that. However, the majority of UVM’s current students in this program did not grow up on a farm. The majority haven't worked on a farm. And so, we're starting from a different level.”

The fact that the current students generally have little hands-on farming experience mandates a new kind of robust education that includes aspects as diverse as farming fundamentals and how to operate farm machinery, while also incorporating the study of food systems and farming’s ecological impacts. These changes have required a broadening of the scope of the curriculum.

Just as the breadth of subjects has changed with the times, the students’ goals for what they want from their education are different as well. Bradshaw describes what he sees as the primary shift, “When folks come here now, they're thinking about social justice, they're thinking about farm workers, they're thinking about livable wages and livelihoods. It's not just, ‘How do I become the next generation to keep the family farm going?’ It's ‘I've never farmed before. I've never even kept a houseplant alive. But I'm really interested in this, and I want to find out how I can contribute to this broader thing of keeping food in our community and integrating agriculture into a landscape that makes sense for our society.’ Our students tend to come from more suburban environments, a decent percentage even are urban. A lot more than you would get in a typical land-grant program.”

Though the new name will appear on future students’ diplomas and transcripts, the real significance of the name change is that it is an indicator of larger shifts taking place both in this particular program and across our broader culture.

The department offers two majors, one of which is Agroecology. Popular courses are Permaculture, Agricultural Policy and Ethics, and Community Entrepreneurship. Agroecology focuses on transforming current food systems using ecologically sound and socially just methods. As alumnus Ethan Pezzini, who graduated from the program this past May, put it, “Agroecology is more than a major; it’s a movement.”

Landscape

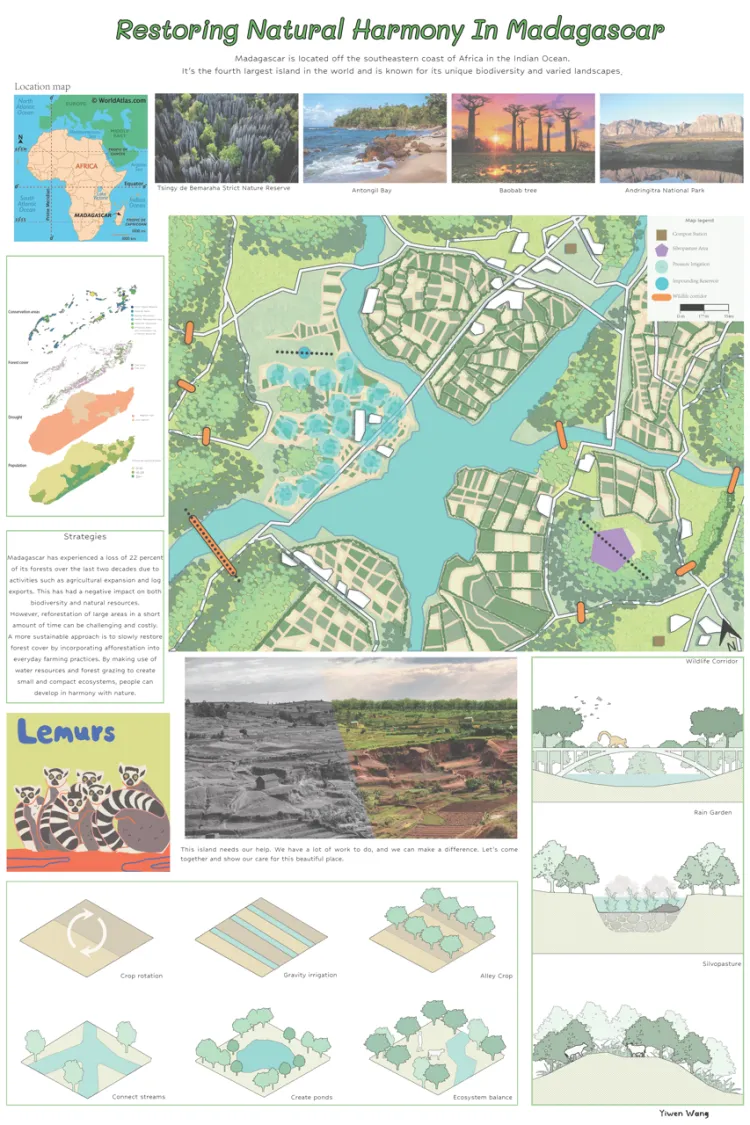

The other major is Landscape Design. “Landscape” here doesn’t refer to the training of landscapers but rather to a philosophy of land use planning that aims to optimize societal, environmental, and agricultural multi-use. Landscape design is an art and a science that supports both natural ecosystems and human livelihoods.

Faculty Fortino Acosta describes the intersection this way, "The teaching of ecologically informed design aids students to understand our role in the intertwined relationship between the built environment and the natural ecosystems. We are another component of nature; we can create coexisting spaces, mitigate our environmental footprint, and foster a more vibrant future."

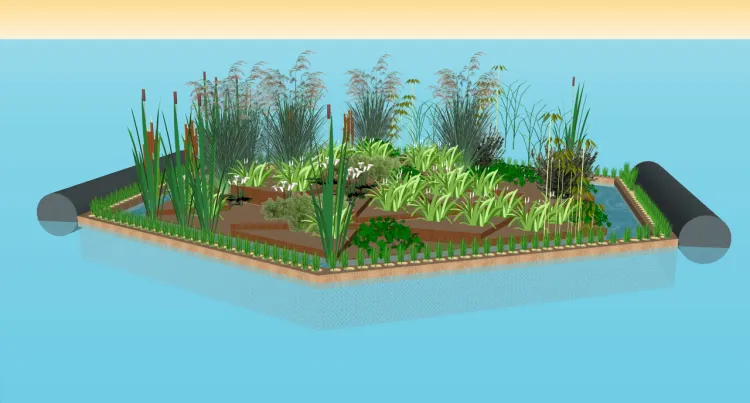

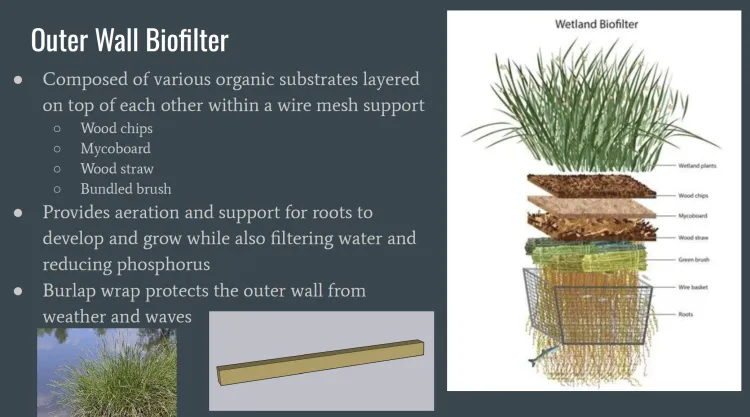

Acosta gave his Landscape Design students an assignment to design aesthetically appealing and functional floating wetlands that could be used to reduce detrimental algae blooms in Lake Champlain. His students left the class so energized that some are now pursuing funding to build the floating wetlands: Inspired design begetting inspiring action.

Stephanie Hurley, who teaches Ecological Landscape Design Studio worked with her students to develop designs to address climate, ecological, and community impacts in two areas damaged by 2023 floods: downtown Montpelier and Burlington’s Intervale. She and her co-instructor, Richard Amore, invited members of the flood commission from Montpelier and farm managers from Burlington’s Intervale to review her student’s final presentations, giving students an opportunity for real-world, professional feedback and, just as importantly, giving policymakers a chance to hear an entire classroom of innovative ideas to help solve these environmental problems. This sort of community collaboration is at the heart of the new program’s identity: Keeping students engaged in the communities they live in, creating real change in the world even while they are still in college. With coursework designed not just for today, but for the world they are going to inhabit.

The future of farming is rapidly shifting. The number of farmers reaching retirement age is at an all-time high, with the average farmer age at 58, according to the US Bureau of Labor Statistics. Over 1 million of the farmers in America today are classified as “beginning” farmers by the 2022 Agricultural Survey, which is 30% of all producers. The US Bureau of Labor Statistics expects 88,000 jobs to open in the field in the next decade. In comparison, BLS expects only 10,000 elementary school teaching jobs will open in the same period. And though the number of individual farms is still shrinking, there is real career opportunity in this area. But what the “area” entails is evolving.

Many of the leaps in science in the past 50 years have happened in agriculture. Plants and seeds are now engineered like drugs by powerful pharmaceutical companies. Soil is no longer seen as “dirt”, a dead chemical substrate, but is now recognized as a living microbiome, a teeming, complex ecosystem filled with a vast number of organisms. Climate change has become a major disruptor of the field. Farmers are one of the frontline occupations to bear witness to the effects of climate change on our environment. As farmers grapple with the impact on their bottom line and observe the outcomes of climate-change-caused disasters, they become increasingly self-interested in mitigation efforts. Since agricultural producers are one of the largest sources of greenhouse gas emissions, from soil tillage to methane gases produced by animal manure, they also can play an important role in climate-change reversal.

Environment

No matter how we feel about climate change, GMO seeds, or AI-informed farming, we all need to be able to eat, so agriculture’s future and land-use planning impacts every person on the planet. That scale of impact is what surveys say that most Gen Zers are looking for from their education: To make a difference. UVM is in an enviable position in this regard, as it was recently ranked first by the Princeton Review as the “Best School for Making an Impact”.

The University of Vermont has also changed several other aspects of its identity this year: rolling out a new university logo and a new brand tagline, “For people and planet”. Additionally, plans are underway to develop a ‘planetary health’ emphasis across all the disciplines. The need for these changes is emerging from similar causes. While colleges across the state and across the nation are facing declining enrollment and, in many cases, forced closures, UVM is enjoying a robust enrollment and a bright future. Many factors are contributing to UVM’s current success in attracting students to its campus in Burlington, but it seems one reason must be UVM’s alignment with current student interests. Programs such as ALE are staying relevant by broadening their field of inquiry and providing academic knowledge grounded in a specific place, as a set of interconnected concerns, or as co-equal parts of a balanced equation.

When asked what he wants the public to understand about the significance of the name change, Bradshaw is quick to answer. “This isn’t aspirational. This is who we are and what we already do. I think the main thing I want people to realize is we are the same people that we've been, but we're doing different things than people might remember from 30 years ago, 20 years ago, or even 10 years ago. It's a new iteration of an existing program. It's the same program that people have interacted with. It's the program that farmers may have interacted with without even knowing it was within a department. I've been answering phone calls for 25 years about apples, and up until a couple of years ago, I had no Extension appointment, but I still picked up the phone. And today, a faculty member such as Yolanda Chen -- she’s an expert on Swede Midge -- people email her all the time asking questions about Swede Midge control. We are all providing some kind of outreach to the community.”

So, raise your glasses and toast the Department of Agriculture, Landscape and the Environment (ALE). Even the department’s acronym is a clever nod to one of Vermont’s favorite artisan crops. ALE is the newest department to sprout in the College of Agriculture and Life Sciences at UVM, but it will surely grow as it is rooted in the plentiful harvest of all that has come before.