"Un-essay projects are art projects that allow you to engage with the material in ways that are more personalized than traditional essays, lab reports, or exams," the syllabus explained.

Rowan feels passionately about the importance of clear and emotionally affecting science communication. "I believe our science is only as good as our ability to communicate it," they explained. The vast majority of people we will work with outside of the academic space will not have the knowledge base we do, which makes effective communication and synthesis paramount. I have had many essay opportunities within my forestry degree that have allowed my writing talent to grow and to demonstrate my ability for effective communication."

Rowan has some advice for students looking to grow in confidence as writers, especially outside of the science and lab report-writing niche. "I recommend being unafraid to break standard grammatical rules as long as it improves your narrative voice, sharing your writing with peers, and writing about something that really matters to you," they advised, If you feel passion about something, it’s hard not to see that in your writing."

Rowan's favorite Rubenstein School experience (so far!) has been taking dendrology. "I took dendrology my freshman year, and enjoyed it so much I decided to declare my major in forestry," they said. "Just being out in the woods and learning to name all these trees I had spent my life with was immensely moving and changed the course of my life."

American Beech

by Rowan McHugh

Fagus grandifolia Fagaceae.

We are walking to Santanoni peak. We've jogged the flat entrance road, and I am optimistically delusional about the amount of time it'll take for me and this newbie to move 18 miles in the woods. Despite the 9 hour timer ticking in my head, I'm still unsure about my hiking companion's ability to survive on the trail, and my nerves will only be validated later when he gets lost and twists his ankle. This is why you don't hike with coworkers. No matter how much they assure you of their athleticism, big muscles don't correlate with common sense, and if anything they may be mutually exclusive, but the data is still out on that one.

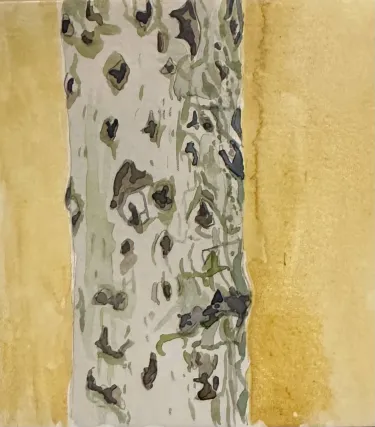

That hasn't happened yet, now we are only a mile into the woods. The trees are getting larger and our conversation picks up as our pace slows. We pass by a large smooth Beech. I pause mid-sentence and step off the trail to slap it.

I tell him it's good luck, for yourself and for the tree. I explain, not many trees are smooth these days, even the young ones are bumpy. Beyond the superstition, there is something satisfying about it. I'm reminded of leaning over my horse, Noble, as he lied in the grass, and the solid sound his body made as I pat him on the shoulder. I'm not delicate, but I'm not forceful. It's a gesture that respects the magnitude of the being I am greeting. To a 15 hand horse or a 30 inch DBH tree, I become a small child in either of their presences.

Back on the trail, I turn to my hiking companion to lament---my poor beech trees. Brown spots and bubbles mark their grey bark like syphilis scars. Their leaves are stained and wilted, striped with the sign of imminent death. I instruct him to look up and search for disease, as long as it won't cause him to trip. I show him how to spot the stripes on the undersides of the leaves, and give him a brief summary of why we are looking.

Beech bark disease, and now Beech leaf disease, tear through our canopies in the northeast, creeping ever northward. I imagine someone slashing a knife through a map of the US. They flick the blade upward, angrily, and the paper peels away from Pennsylvania, New Jersey, and New York. Over time the hole expands, it peels around the edges of the gash, shreds along highways and ripping into stands that should be protected deep in the wilderness. There is no way to know what will become of the gap forming in our canopies, especially with the uncertainty climate change introduces. I suspect like the elm and chestnut before them, the end of an era is coming. We are in hospice.

When I tell my coworker to look, I phrase it like a mission. I say it is important, and that the information can be used for management practices across the Adirondacks. But honestly, the chances that my reporting will go anywhere are slim. I just want to teach this stranger to care like I do.

Confirming the presence of a disease in an area becomes a weirdly political matter. Sure for things like ebola, covid, or eastern equine encephalitis, it makes sense to be absolutely sure before you spark panic. But for the foresters who see it, with their own eyes in their back yards, confirming it to any kind of authority is a process of litigation and fact checking that makes you wonder if they want people to know, or care, at all about forest health. Not that many do to begin with.

Beech bark disease has been in my woods for as long as I've remembered. Before I knew how to identify trees by their buds and branching patterns, back when the only leaf I knew was a maple, and spruce, cedar, and hemlock were all called "pine," I knew the Beech trees for their bumps. If you showed me a smooth one, I don't know that I would've correctly identified they were the same species. I mean you can hardly blame me. Buck was the one who named them to me. Spoken out loud, I heard "Beach trees" and I pictured them lining a Massachusetts coast line. I didn't know that down past the overlook, on land that isn't mine, the brilliant yellows I passed every fall were composed of a monoculture of Beech. The council of old trees by that creek turn the ground, the sky, and the walls around you a brilliant marigold in early October.

I would ATV along this path with my family on Columbus Day Weekend, before the land changed hands and the trails became unmanageable. This patch feels like stepping into a story book. Every time I smell the sweetness of leaf decay, when the thick litter lining the forest floor becomes soft and damp from rain, I am reminded of those Beech. As much as monocultures pose a threat, especially in the context of disease, I cannot deny that the uniformity of this stand added to its beauty. The speed of the ATV blurred the world into a yellow haze. I gripped Fawn tightly as she whipped us around corners. I sang to myself over the motor and drank in the smell of the gas when we idled, waiting for the others to catch up. I hardly stopped to look at their bark in this state, but I can still close my eyes and see the color all around me.

This time of year is also when infection begins.

Beach Bark disease is more of a syndrome than a single pathogen. It begins with the Beech scale insect, Cryptococcus fagisuga. The Beech scale insect population in North America is all female, meaning they reproduce parthenogenically. I joke that bugs are just shapes that reproduce, but for these small minimally mobile insects, I'd argue I'm not far off. These bugs came from Nova Scotia in the 1800s. There is some evidence they prefer trees with rough bark, meaning my superstition was right, the smooth ones really are the lucky ones.

Once the tree is weakened, several species of fungi like Neonectria faginatam and Bionectria ochroleuca take over and begin to ravage their host. Their bark forms bubbles like those on overcooked pizza crust and their cores get weaker as cankers tear through their heart wood. They become susceptible to wind damage and the large trees die first. Young Beech take over the understory and choke out other regeneration.

It's because of the chokehold understory Beech has in New England that some are excited about the end of Beech. With their unmatched shade tolerance and tenacity after cutting, Beech thickets are a common sight, and a pain in the ass to those who favor more commercially valuable stems. Beech will sucker-sprout with fury. It takes several years and good timing to successfully cull a stand. So you could hack and squirt with pesticides, you could employ goats to come and graze for you, you could burn or cut and cut again until the starch runs out and the Beech is finally slayed, or you could simply wait for Beech leaf disease to come and clear the area for you.

Beech leaf disease is caused by a nematode that is thought to have originated in Japan. Opposite to Beech Bark disease, the young trees are the most vulnerable because they lack the substantial starch storage needed to sustain themselves after systemic leaf damage. Trees will stand for years and years even after severe cases of Beech bark disease, but the same cannot be said for Beech leaf disease. Characterized by dark stripes in their leaves, the mark of Beech leaf reminds me of a sash on a beauty pageant queen. From infection to death, young trees may not even last 5 years. In a forest, 5 years is a blink in the eye. Death in 5 years is a shock to the system, not a slow decay but a stab wound.

The question in my mind is not how do we save the Beech, it's not even how long until beech leaf disease decimates my neck of the woods, but who will fill in for Beech once they’re mostly gone? People are already casting their runner ups.

Beech is a masting tree. On a cycle lasting 2-8 years, as their leaves turn from green, to yellow, to dusky copper in the fall, they also drop large amounts of beechnuts which feed turkeys, deer, squirrels, and even bears as food gets scarce and the days get shorter. Even diseased Beech can support pileated woodpeckers, black-capped chickadees, and tufted titmouse in their cavities. Foresters suggest planting oak once they're gone in Vermont, since their acorns may supplement the loss of beechnuts and oak trees can tolerate the warmer temperatures inevitable due to climate change. Sugarers are cautiously excited about expanding the sugarbush. Landowners discuss planting shagbark, white oak, and even new varieties of resistant American chestnut. Whatever happens, it's certain something will fill the gap. In a northern hardwood forest, sunlight never goes to waste.

I am not overly attached to Beech trees. Perhaps in their heyday I may have been. There is one Beech, it stands near Bolton, VT, on a property called Bear Island. I met it while on the property for a forestry class, discussing the benefits of "messy" logging for bird habitat and forest regeneration. To this day, it is the largest and smoothest Beech I have ever seen, and of course even as I followed my classmates up the hill in a single file line, I leaned out to give it the heartiest good luck slap I could. The trunk met my palm with a sting, like a high five with perfect contact. "What a beaut," I said out loud, to no one other than the tree. I thought it deserved to hear the compliment. I thought if every Beech looked like that, maybe I'd feel the incoming loss was much greater. If it were my eastern white pines, or my sugar maples, or my pitch pines or balsam fir, maybe I'd feel more bitterness and rage. But I think there is a blessing to this somewhat mild emotion. The Beech may not be what they had been to generations of people and animals, but I got to spend a childhood in golden light all the same. There may be grief in what could've been, but it won't kill me.

I am so scared of the world going away before I get to see it, of nature disappearing or changing beyond what I recognize. It paralyzes me. But I must make myself understand that the world has already changed before I got here; the Beech are not what they once were, and that it is okay. Maybe your grief and your anger fuel you, but they don't fuel me. So I must fold the knowledge of change into myself, I need to understand so deeply that my brain will fire a new pathway, one that doesn’t see the death of Beech as unsurvivable. One that doesn't view loss as something that must be clawed and fought against.

A friend once said to me, let go or be dragged. When people I’ve loved with all my heart have told me they don't want to be in my life anymore, I've felt the anchor drop. I still feel, at times, incapable of letting go. But maybe one day I will be able to see our bright moments, the warm memories that pass me by, as good luck charms, just like smacking a lone smooth Beech, before carrying on with my day, with my hike, because we are only at the beginning. There are miles to go, and it's easier without the weight.

My coworker misses a cairn at mile 14 denoting a stream crossing and walks right down the stream bed instead. I'm further on the trail, and getting suspicious at the silence behind me, so I double back, screaming bloody murder trying to find where he could've gone. Finally, I can hear his voice echo up the mountain, and he sounds hurt. I burst off the trail and I push myself through balsam needles up to my knees. Branches scrape my arms and stomach and the ground frequently falls out from under me. I groan and bitch to myself, calling out to coworker telling him to keep yelling so I can find him. For someone who ends up off trail as often as I do, I positively hate bushwhacking.

I return to the stream bed, and it's steeper here. The stone walls on either side are high, and the water depth periodically goes above my head. At this point, I'm panicked. I call 911, and begin to transmit my location via satellite before I drop my phone in the water trying to shove it in my back pocket. When his yelling stops, I move faster. I duck back into the woods when the bed gets too slippery, trying to be efficient but not crack my skull. I'm cut up, my legs burn, and my boots are soaked from running through the water, but I move forward with as much determination as I can manage. I play the blame game in my head. He's an adult, he makes his own decisions, but I brought him out here. I went on ahead, I lost him, and now I have to find him and get us out of here so I can study for my exam at 6am the next day.

Finally I see the smoke. I find him sitting by a small fire, with no visible injuries or deformities. He tells me he rolled his ankle, but that he is otherwise no worse for the wear. I sigh, letting the stress drain out of me even though it takes a great deal of energy with it. I kneel at his feet to construct a makeshift brace out of a bandana and safety pins. He says he is sorry. "You're ok", I say, "and that's what matters. Good work with the fire. You're lucky I found you, you would've been out here all night.”

I thank the Beech in my head.

Citations

American beech: a valuable tree for wildlife | Lake Metroparks. (2024, December 26). Lake Metroparks. https://www.lakemetroparks.com/along-the-trail/march-2021/american-beech-a-valuable-tree-for-wildlife/#:~:text=Wild%20turkeys%2….

Beech leaf disease: An emerging forest threat in Eastern U.S. | US Forest Service. (n.d.). US Forest Service. https://www.fs.usda.gov/inside-fs/delivering-mission/sustain/beech-leaf-disease-emerging-forest-threat-eastern-us

Wildlife, T. a. F. (n.d.). The Future of Beech in New Hampshire. Taking Action for Wildlife. https://www.takingactionforwildlife.org/blog/2025/01/future-beech-new-hampshire

Bose, A.K., R.G. Wagner, B.E. Roth, and A.R. Weiskittel. 2017. Influence of browsing damage and overstory cover on regeneration of American Beech and Sugar Maple nine years following understory herbicide release in central Maine. New Forests. 49:67-85.

Cale, J.A., M.T. Garrison-Johnston, S.A. Teale, and J.D. Castello. Beech Bark Disease in North America: Over a century of research revisited. 2017. Forest Ecology and Management. 394: 86-103.

Calic, I., J. Koch, D. Carey, C. Addo-Quaye, J.E. Carlson, and D.B. Neale. Genome-wide association study identifies a major gene for Beech Bark Disease resistance in American Beech (Fagus grandifolia Ehrh.). BMC Genomics. 18:574.

Dracup, E.C., D.A. MacLean. 2018. Partial harvest to reduce occurrence of American beech affected by Beech Bark Disease: 10 year results. Forestry. 91:73-82

McCullough, D.G., R.L. Heyd, and J.G. O’Brien. 2005. Biology and Management of Beech Bark Disease. Michigan State University. Extension Bulletin E-2746.

Ontario Ministry of Natural Resources and Forestry. 2016. Beech Bark Disease. ontario.ca/page/beech-bark-disease

Stephanson, C.A. and N.R. Coe. 2017. Impacts of Beech Bark Disease and Climate Change on American Beech. Forests. 8, 155.

Wiggins, G.J., J.F. Grant, and W.C. Welbourn. 2001. Allothrombium mitchelli (Acari:Trombidiidae) in the Great Smoky Mountains National Park: Incidence, Seasonality and Predation on Beech Scale (Homoptera: Eriococcidae). Ecology and Population Biology. 94: 896-901.

Wisconsin Department of Natural Resources. 2015. Management of Beech Bark Disease in Wisconsin. dnr.wi.gov/topic/foresthealth/beechbarkdisease.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2025/08/13/realestate/beech-leaf-disease.html