Psychoactive Plants

Maybe these will change your mind!

For just as long as humans have been using plants for healing and medicinal purposes, we have been using them for their mind-altering properties as well. Many of us are no stranger to the effects of some of the more commonly used psychoactive plants, like marijuana (Cannabis sativa) or tobacco (Nicotiana tabacum), or even coffee (Coffea arabica). While these plants are now widespread and have been used since long ago, there are many other kinds of psychoactive and poisonous plants, and many other traditional uses that have persisted for thousands of years.

Coffea arabica is the most widely consumed psychoactive plant in the world, with an estimated one billion people having a cup of coffee to start their morning every day. While we know that caffeine is the drug in coffee that makes us feel more awake, we might not think about the fact that we are consuming a psychoactive stimulant at the start of every day. Caffeine stimulates the central nervous system, heart, muscles, and the centers that control blood pressure.

On the left is a particularly well preserved specimen of "Coffea arabica" collected in 1994 in Dominica. On the right is the same species of plant collected almost exactly 100 years earlier in Mexico. The coffee plant is native to Ethiopia, but is now cultivated in many parts of the world, including where these specimens were found. Both are now housed in the Pringle Herbarium.

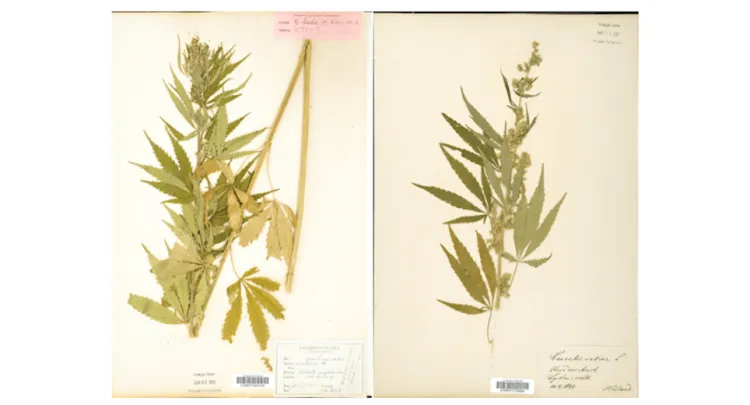

Cultivation of Cannabis sativa likely began as early as 12,000 years ago in Central Asia, according to paleobotanical research. This plant was likely first grown for its hemp fibers as opposed to its psychoactive properties. The theory goes that the people cultivating the plant may have accidentally stumbled upon the other benefits that it had to offer, and then began breeding the plant with the intent of increasing the content of THC, its main psychoactive component. THC affects parts of the brain that release dopamine and glutamate, which can alter mood, perception, and cognitive functions. There is evidence of usage in mortuary ceremonies in Western China from about 2,500 years ago, and these particular plants had high levels of psychoactive compounds.

The Pringle Herbarium has 67 specimens of "Cannabis sativa". Both of these specimens were collected over 100 years ago; the one on the left is from Whiting, Vermont.

As is expected with a plant with such an extensive history, there have been many books and research articles published on cannabis, on a range of topics, including its history, domestication, and usage. The UVM libraries are homes to many such books, such as Reefer Madness: The History of Marijuana in America by Larry Sloman, found in the Howe Library, which provides a history of social cannabis use in the United States. Another, Marijuana, by Mark S. Gold is housed in the Dana Health Sciences Library, which focuses more on the medical and psychoactive uses and abuses of the drug.

These two books, among many others, are available in the Howe Library (left) and Dana Health Sciences Library (right).

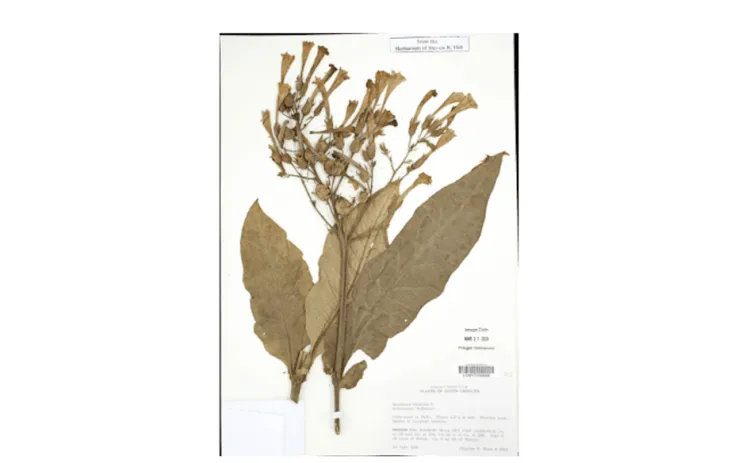

Another very commonly consumed plant drug is tobacco, which also has a very long history of use. Nicotiana tabacum is found in the Solanaceae or nightshade family, which is known for having some incredibly poisonous plants, as well as some that we consume on a daily basis, like tomatoes and potatoes. Nicotine, the primary psychoactive chemical in tobacco, causes the brain to release dopamine, just like THC, and is why users find it so enjoyable, and also incredibly addictive. The usage of tobacco goes back as far as the first century BCE, where archeologists have found evidence of the Maya people of Central America smoking tobacco leaves during religious ceremonies. The plant made its way up into North America, where indigenous leaders also developed the use of the plant for both spiritual/religious and medicinal purposes. It is likely that Europeans brought back the practice of smoking tobacco in the 15th and 16th centuries during the early years of colonialism, which would eventually lead to tobacco becoming the commercialized cash crop that it is today.

The Pringle Herbarium is home to just 4 specimens of "Nicotiana tabacum". This one was collected about 30 years ago in South Carolina. As the label mentions, this plant is native to South America and the Caribbean, and while still grown in many Southern US states, the number of tobacco farms is declining.

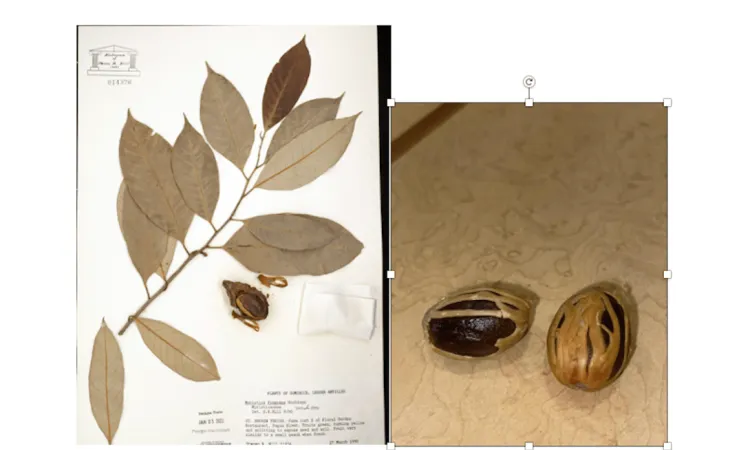

All the previously mentioned plants are very well known psychoactives, but there are many more plants that can affect the brain that you might keep in your own kitchen. One of these is nutmeg (Myristica fragrans); this spice often used in holiday baking contains hallucinogens if consumed in large enough quantities. Most recipes using nutmeg require no more than half a teaspoon—a safe amount—but consuming nearly two tablespoons can cause acute toxicity because of its effects on the brain. The compounds myristicin and elemicin in nutmeg are what can cause harmful effects, such as delirium, confusion, and dizziness at lower amounts, and hallucinations in higher volumes.

On the left is a specimen of nutmeg from the Pringle Herbarium collected in 1990 by Steven Hill, who donated his entire collection of over 35,000 specimens to the Pringle. On the right are enlarged images of the nutmeg fruit, a drupe that is used to produce the nutmeg spice from the seed, and mace from the aril (seed covering).

Many people grow sage (Salvia spp.) in their gardens and use it as a spice in cooking without realising that our common species of kitchen sage have a hallucinogenic relative. While there are many species and cultivars of sage from the mint family that are popular in gardens for their bright flowers, there is one species in specific, Salvia divinorum, that contains a chemical thought to be the most potent known hallucinogen of a natural origin. Species of Salvia are native to many parts of the world, including the Americas, Europe, Asia, and Africa, but Salvia divinorum specifically is endemic to a small region of Oaxaca, Mexico known as Sierra Mazateca, where it has been used in religious rituals for hundreds of years.

The active ingredient in the plant, Salvinorin A, can cause intense hallucinations, altered concepts of time and space, and changes in body sensations and perception. The drug can be ingested by chewing the plant, holding fresh leaves under the tongue, or by being dried and smoked. The Mazateca people have long used this plant to treat health issues, such as headaches and rheumatism, as well as for ceremonial purposes.Even though many species of Salvia are found in our gardens, the potent effects of Salvia divinorum have led to it being classified as illegal in 33 US states, with some allowing it strictly for aesthetic purposes only.

The book on the left is fully available online in PDF format through the Howe Library. It goes in depth on uses of common sage ("Salvia officinalis") as a natural pest deterrent, as well as examining its health benefits and its cytotoxicity. The image on the right is a specimen of "Salvia stolonifera" collected from Oaxaca, Mexico, where "Salvia divinorum" is also native. Despite the Pringle Herbarium housing over 700 specimens of various "Salvia" species, it does not contain a single specimen of "Salvia divinorum".

There are many more plants that can have psychoactive and hallucinogenic effects on the brain than I have mentioned here, as well as many more resources about them at UVM. One particularly good example is a book at the Howe Library by Richard Evans Scultes, a renowned ethnobotanist, and Albert Hofmann, a Swiss chemist, called The Botany and Chemistry of Hallucinogens. Another is The Encyclopedia of Psychoactive Plants, by Christian Ratsch, kept in the Pringle Herbarium’s library. This book is an excellent resource and contains information on over 400 plants and their psychoactive effects.

These are two books available at UVM that have copious amounts of information on more psychoactive plants from all over the world, and the chemistry behind how these plants affect the brain. They are found in the Howe Library and Pringle Herbarium Library, respectively.

By Kylie Roth

References

Cambron, M. (2016,). A comparison of historical and current use of Salvia divinorum in the United States and Mexico. Lake Forest College. Retrieved November 15, 2024, from https://www.lakeforest.edu/news/a-comparison-of-historical-and-current-use-of-salvia-divinorum-in-the-united-states-and-mexico

Chadwick, P. (2016). In Celebration of Salvias. Piedmont Master Gardeners. Retrieved November 15, 2024, from https://piedmontmastergardeners.org/article/in-celebration-of-salvias/

Crorq, M.-A. (2020. History of cannabis and the endocannabinoid system. Dialogues in clinical neuroscience, (22)3, 223–228. https://doi.org/10.31887/DCNS.2020.22.3/mcrocq

Evans, J., Richards, J. R., & Battisti, A. S. (2024,). Caffeine. StatPearls. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK519490/

Kashouty, R. (n.d.). Medical Marijuana and Its Effect on Neurotransmitters. Premier Neurology. Retrieved November 15, 2024, from https://premierneurologycenter.com/blog/medical-marijuana-and-its-effect-on-neurotransmitters/

Lawler, A. (2019). Oldest evidence of marijuana use discovered in 2500-year-old cemetery in peaks of western China. Science. Retrieved November 15, 2024, from https://www.science.org/content/article/oldest-evidence-marijuana-use-discovered-2500-year-old-cemetery-peaks-western-china

Mishra, S., & Mishra, M. B. (2013). Tobacco: Its historical, cultural, oral, and periodontal health association. Journal of International Society of Preventative and Community Dentistry, (3)1, 12-18. https://doi.org/10.4103/2231-0762.115708

Petruzzello, M. (2024). Diviner’s sage | Description, History, Hallucinogen, Drug, Uses, & Facts. Britannica. Retrieved November 15, 2024, from https://www.britannica.com/plant/salvia-plant-species

Ren, M., Tang, Z., Wu, X., Spengler, R., Jiang, H., Yang, Y., & Boivin, N. (2019). The origins of cannabis smoking: Chemical residue evidence from the first millennium BCE in the Pamirs. Science Advances, (5)6,. https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aaw1391

Smith, M. (2014). Nutmeg. Encyclopedia of Toxicology, 3, 630-631. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-0-12-386454-3.00762-4

Zawilska, J. B., & Wojcieszak, J. (2013). Salvia divinorum: from Mazatec medicinal and hallucinogenic plant to emerging recreational drug. Human Psychopharmacology, (28)5, 403-412. https://doi.org/10.1002/hup.2304