Poisons Beyond Ivy and Parsnip

Plants are often used for good, but not always.

I believe it is safe to say that a large majority of our interactions with plants on a daily basis are beneficial, or, at the very least, unremarkable. We eat plants every day, walk by them outside, perhaps wear them on our bodies, or care for them in our homes or gardens. Plants are not only important to us in many ways artificially and aesthetically, but also keep us alive. They turn our carbon dioxide into breathable oxygen, provide us with nourishment, and filter toxins out of our ecosystems. However, anyone who has ever dealt with the aftermath of unknowingly brushing up against a patch of poison ivy (Toxicodendron radicans) knows that plants can be a nuisance under certain circumstances, and some effects of plants can be far more detrimental than a mere rash. Some plants produce poisonous chemicals as a way to protect themselves from predators, insects, and microorganisms that seek to feed on the plant. While there are plant toxins that have been harnessed for good such as in the medical community, as biopesticides, or to catch fish, there are many plants with high levels of toxicity that have been manipulated with wicked intentions, or have harmed people through accident or misuse.

One plant that can be exceptionally dangerous if not handled carefully is Ricinus communis, which you may know as the castor oil plant. Ricinus communis is a member of the Euphorbiaceae family, which contains several other toxic plants, and is also home to the poinsettias, which are often falsely accused of being highly toxic to pets. The castor oil plant produces ricin, a lectin (a type of protein), in its seeds. This protein affects the body by interfering with the creation of other proteins that are vital to cell function. Ricin can be ingested, inhaled, or injected, and symptoms of the poisoning can reveal themselves within hours and can include fluid build up in the lungs, seizures, and death in extreme cases. This compound has actually been used experimentally to kill cancer cells because of its toxic nature.

Ricin is not a poison that someone would likely ever come in contact with accidentally, but it has been used in murderous plots, such as the 1978 death of Georgi Markov, a Bulgarian journalist who was attacked and had a ricin pellet placed under his skin. Adding to the nefarious history of the plant, the United States military experimented with the poison in the 1940s testing its potential for applications in biological warfare. The entirety of the plant is not toxic, as the seeds must be broken open to release the toxic protein, and so is commonly planted for the animated aesthetic of the large palm shaped leaves and bright red fruits.

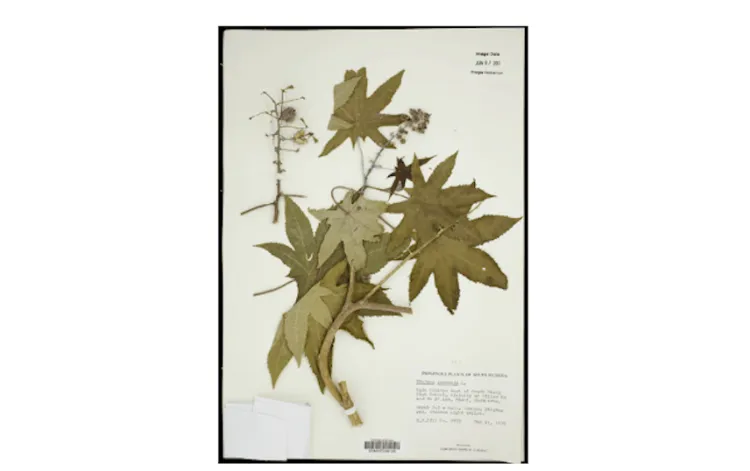

This is the only specimen of "Ricinus communis" in the Pringle Herbarium. It was collected in Floridaby Steven Hill in 1975.

This is a photo of "Ricinus communis" from the garden behind the Jeffords building at UVM. Despite this plant’s exceptionally poisonous nature, it makes for a beautiful addition to the garden as the toxin is safely contained within the seeds and away from garden-goers.

One of the best-known poisonous plants is Atropa belladonna, commonly known as deadly nightshade. It is a member of the Solanaceae family, often considered one of the most toxic plant families. This plant is native to Europe, North Africa, and Western Asia, but has been naturalized in many parts of the world, including parts of the western United States and New York. This plant contains toxic alkaloids that block the action of important neurotransmitters that are needed for the brain to communicate with muscles. Atropa belladonna disrupts the parasympathetic nervous system, which is responsible for involuntary functions like breathing and heart rate. Depending on the amount ingested, the symptoms can range from dilated pupils and confusion to hallucination and—rarely, but possibly—death. This is because, unlike ricin, the toxic compounds in this plant have an antidote in the form of an anticholinesterase or a cholinomimetic, which are widely available in medical settings.

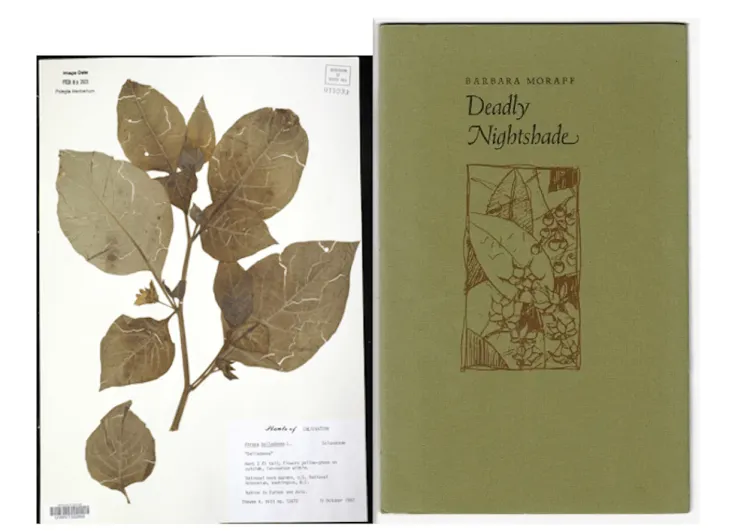

On the left is the sole specimen of Atropa belladonna in the Pringle Herbarium, and it is from a collection of cultivated plants. This particular specimen comes from the National Herb Garden in Washington, D.C. On the right is the book, "Deadly Nightshade", by Barbara Moraff, a celebrated poet from the 'Beat Generation' of the mid-to-late 20th century; this volume focuses on themes centering on the human condition and experimenting with hallucinogenic drugs. This collection of poems is 1 of only 400 ever produced, and can be found in the Silver Special Collection Library.

Datura is another genus of plant in the Solanaceae family in which all species contain toxic tropane alkaloids, such as hyoscyamine and scopolamine. For the most part, the nine recognized species of Datura have been naturalized across Europe, Africa, and Asia, and have records of being in some of these places for thousands of years; despite this, they likely all originated from Mexico or parts of Central America. The effects of the toxins in the plant include hallucinations, seizures, and death in extreme cases.

Datura has been used historically in Aztec rituals and sacrifices as a painkiller or narcotic.

It is also known for its speculated use in the process of “zombification” in the Caribbean, and is sometimes called the “zombie-cucumber” for this reason. The plant was theorized to have been used to incapacitate victims before being buried, only for the victims to then awaken and seemingly rise from the dead as a zombie.

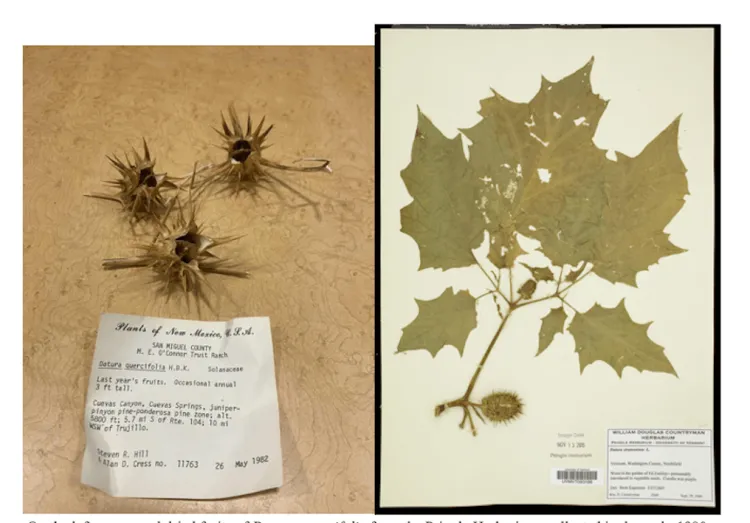

On the left are several dried fruits of "Datura quercifolia" from the Pringle Herbarium, collected in the early 1980s. On the right is a specimen of "Datura stramonium" collected in Vermont in 1969. The spiked seed pod is what gives "Datura" one of its common names: thorn apple.

"The Serpent and the Rainbow" by Wade Davis was published in 1985; it tells the true story of Davis’s travels to Haiti to investigate ethnobotanical poisons, such as Datura, and their roles in cases of people who had become “zombies.” This book is available to be checked out at the Howe Library. This book inspired a movie of the same name that was released in 1988, and has since been the subject of some controversy in the scientific community.

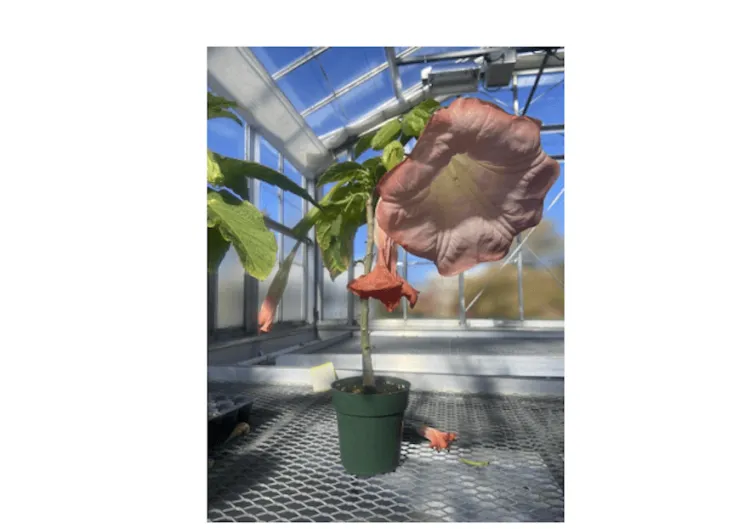

Brugmansia, yet another dangerous genus within the Solanaceae family, is commonly called angel’s trumpet due to its large, pendulous, tube-shaped flowers. The toxic compounds in Brugmansia are the same as in Atropa belladonna and Datura spp., and so consuming the plant’s flowers or leaves can cause nausea, blurred vision, and hallucinations. Despite its toxicity, the plant has been used by Indigenous peoples in rituals or as an herbal medicine in South America. People have been known to consume the plant’s flowers to purposefully induce hallucinations, but the hallucinations are often unpleasant and frightening at best, and measuring a safe dose that will not lead to death or serious health consequences is nearly impossible.

This is a live specimen of "Brugmansia" kept in the UVM Greenhouse, showing off its large, pink, highly toxic flowers. UVM’s greenhouse is home to not only many established plants in their living collections, but also grows plants for use in many courses on campus, as well as for regular plant sales.

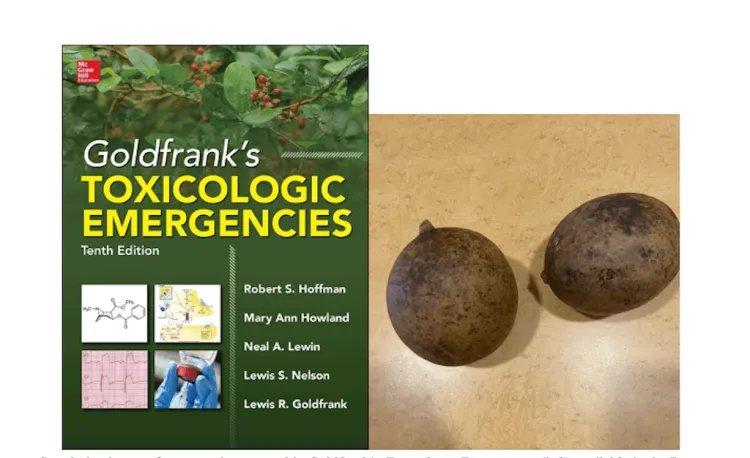

To move away from the Solanaceae family, the Loganiaceae family contains a highly toxic genus called Strychnos, which produces a similarly named toxic alkaloid, strychnine. There are around 200 species of Strychnos that all contain toxins, but the poison is typically derived from three species that are native to Southeast Asia (India, West Indies, Sri Lanka, and Indonesia) and Australia. It is most commonly sourced from Strychnos nux-vomica. Strychnine was first used as a rat poison in the 16th century in Germany, and is still used for this purpose today. If ingested, strychnine acts quickly in the body and can cause respiratory failure and seizures, among other symptoms. Strychnine has been used in various murder plots, and was the popular choice for poisonings in literature, such as in novels by Agatha Christie and in Arthur Conan Doyle’s Sherlock Holmes.

Strychnine is one of many toxins covered in Goldfrank’s "Toxicologic Emergencies" (left) available in the Dana Medical Library at UVM, and is available to be checked out to all UVM students and staff.. This is an excellent resource for medical students and those studying poisons, as the book contains information on all aspects of poison management from effects on the body to how to manage them. The Pringle Herbarium features two large preserved fruits from "Strychnos nux-vomica" (right).

There are thousands more plant species that contain toxic components, some that we come into contact with everyday. Even something as nonchalant as kidney beans contain a toxin that can cause less than ideal gastrointestinal issues if the beans are not thoroughly cooked before eating. Luckily, most of us do not encounter the negative effects of many poisonous plants in our everyday lives, but they are still all around us; UVM has many resources for learning more about them.

These are two great resources available on poisonous plants at UVM. The book on the left focusing on the nightshade (Solanaceae) family, is available at the Howe Library. The book on the right covers approximately 350 plant species and their botanical, geographical, pharmacological, and toxicological data. It can be found in the Pringle Herbarium’s library.

By Kylie Roth

References

Bradbury, N. (2022, February 9). A Brief History of Strychnine, the Poison of Choice for Agatha Christie, Arthur Conan Doyle, and Scores More—But Why? CrimeReads. Retrieved November 15, 2024, from https://crimereads.com/strychnine-poison-christie-conan-doyle/

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2018, April 4). Facts About Ricin. Retrieved November 15, 2024, from https://emergency.cdc.gov/agent/ricin/facts.asp

Fensterstock, A. (2019, March 1). High Among the Angels. 64 Parishes. Retrieved November 15, 2024, from https://64parishes.org/high-among-the-angels

Guercio, G. D. (2017, October 31). The Secrets of Haiti’s Living Dead. Harvard Magazine. Retrieved November 15, 2024, from https://www.harvardmagazine.com/2017/10/are-zombies-real

Henningfield, J., & Rose, C. A. (2024, November 14). Smoking - Health Risks, Addiction, History. Britannica. Retrieved November 15, 2024, from https://www.britannica.com/topic/smoking-tobacco/A-social-and-cultural-history-of-smoking

LiverTox. (2017, July 7). Anticholinergic Agents. Retrieved November 15, 2024 from https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK548287/

Lockett, E. (2022, November 14). What You Need to Know About the Effects of Angel’s Trumpet Poisoning. Healthline. Retrieved November 25, 2024, from https://www.healthline.com/health/angel-trumpet-effects

Missouri Botanical Garden. (n.d.). Atropa belladonna - Plant Finder. Retrieved November 15, 2024, from https://www.missouribotanicalgarden.org/PlantFinder/PlantFinderDetails.aspx?taxonid=287159

National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health. (2011). Strychnine: Biotoxin. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Retrieved November 15, 2024, from https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/ershdb/emergencyresponsecard_29750018.html

USDA Forest Service. (n.d.). The Powerful Solanaceae: Datura. Retrieved November 15, 2024, from https://www.fs.usda.gov/wildflowers/ethnobotany/Mind_and_Spirit/datura.shtml

Rahn, J. (2011). The Beat Generation - Literature Periods & Movements. The Literature Network. Retrieved November 15, 2024, from https://www.online-literature.com/periods/beat.php

Sandridge, S. (2014, July). Toxic Beans. State Food Safety. Retrieved November 15, 2024, from https://www.statefoodsafety.com/Resources/Resources/toxic-beans

Strychnine: Biotoxin | NIOSH. (2011, May 12). CDC. Retrieved November 15, 2024, from https://www.cdc.gov/niosh/ershdb/emergencyresponsecard_29750018.html

Wang, D., & Wu, A. M. (2007). Carbohydrate Microarrays for Lectin Characterization and Glyco-Epitope Identification. Analytical Technologies. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-044453077-6/50008-9

Wang, D., & Wu, A. M. (2007). Carbohydrate Microarrays for Lectin Characterization and Glyco-Epitope Identification. Analytical Technologies, 167-192. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-044453077-6/50008-9