Plants and People: An Introduction to Ethnobotany

What is ethnobotany and why does it matter?

If you are anything like me and are fascinated with plants, you might be surprised to learn about a discipline within the botany world that is not as well talked about as it should be. Despite being an avid plant enthusiast, I had not heard of ethnobotany until this year. Ethnobotany, as you can gather from the word itself, includes “ethno” referring to people and culture, and “botany” meaning the study of plants. This discipline bridges the gap between botanical and social sciences, such as anthropology. Beyond this, ethnobotany ties in areas of study including—but not limited to—environmental studies, chemistry, and more.

Likely as long as humans have been on Earth, we have been utilizing plants as sources of food, shelter, medicines, and tools. When we put it in a modern context, something as simple and seemingly obvious as the wood used to build your house or the leaves in your tea are ethnobotanical uses of plants; many of us often fail to stop to think about where those plants came from, what they look like, how we can collect and use them, or who was the first to figure out that we could. An ethnobotanist studies how people utilize the plants in their natural surroundings, and works to document traditional knowledge around them so that it can continue to be used by future generations.

The term “ethnobotany” was coined in 1895 by an American botanist named J.W. Harshberger, but the study of the cultural uses of plants has existed for centuries before this. While it is largely seen as a Western science emerging from colonialism and the Enlightenment, other cultures have produced books on the beneficial uses of plants long before this. The past few hundred years especially have seen a great rise in the number of ethnobotanical collections. These are sometimes referred to as “economic botany” collections, reflecting the economic importance of many of these plants. These kinds of collections are housed in museums, herbaria, and university departments that study relevant themes.

While it is likely that some of the earliest publications on the use and applications of plants have since been lost to us, there are a couple of known volumes that date back several centuries or even thousands of years. While not a book, the oldest known written evidence of preparing plants for medicinal purposes was found on a Sumerian clay slab from Nagpur, India, which is approximately 5000 years old. It showed twelve recipes for preparing drugs from plants, and references over 250 individual plants, including mandrake (Mandragora officinarum) and poppy (Papaver). The Chinese emperor Shen Nung is said to have written a book titled Pen T’Sao circa 2500 BCE, which focuses primarily on roots and grasses, with over 365 different drugs described.

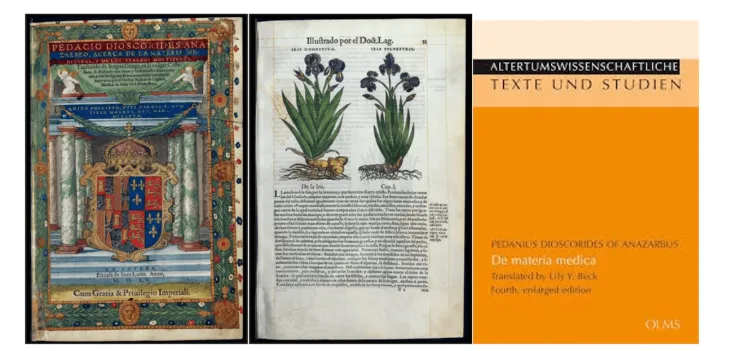

The two images on the left are from a PDF copy of "De Materia Medica" by Dioscorides available online for free from the US Library of Congress. Some of the original manuscripts of this book are held in national libraries, such as those of Austria and China, and the monasteries of Mount Athos in Greece. The image on the right is the first modern English translation of the book, which is available from UVM’s Howe Library.

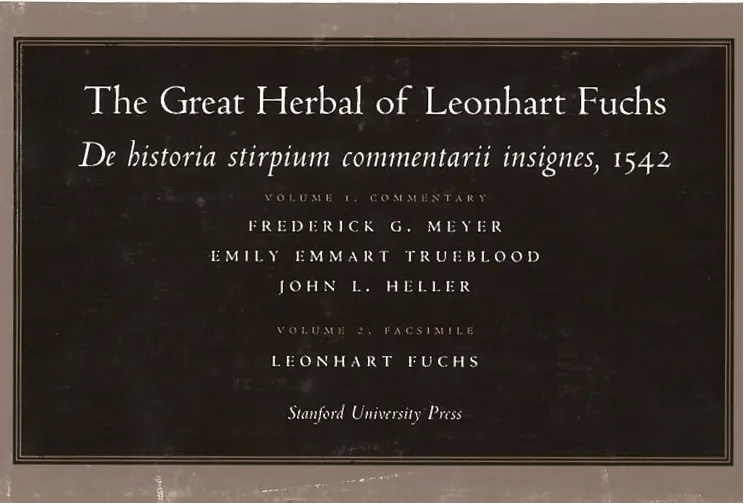

Some of the first known publications that had major influences on the subsequent history of ethnobotany and the usefulness of plants include De Materia Medica, by the Greek surgeon Dioscorides in 77 CE. This volume included information about approximately 600 Mediterranean plants and their uses for medicine at the time, and was translated into Arabic, Spanish, and Latin by the 1500s. Another, De Historia Stirpium, by Leonhart Fuch,s was written in 1542 and cataloged 400 plants native to Germany and Austria, along with images, descriptions, and the medical uses of each plant. Such volumes were not limited to Europe; the book titled Bencao Gangmu, known in English as “Compendium of Materia Medica” was published by Li Shizhen in China in 1593. At the time, this publication was largely overlooked by the Ming Dynasty, but after Shizhen’s death, the book would go on to be republished and translated for centuries after.

This is a facsimile copy of "De historia stirpum" by Leonhart Fuchs that is available at UVM’s Howe Library.

A sharp increase in ethnobotanical collecting and exploration took place as European powers moved west, and also began their age of conquest globally. They began to gather information about how indigenous peoples used plants in the Americas, as well as in Africa and Asia. The 18th century, the age of the Enlightenment sparked curiosity about the natural world, and coupled with colonialism, explorers were encouraged to gather as many artifacts and as much information as they could for displays and museums.

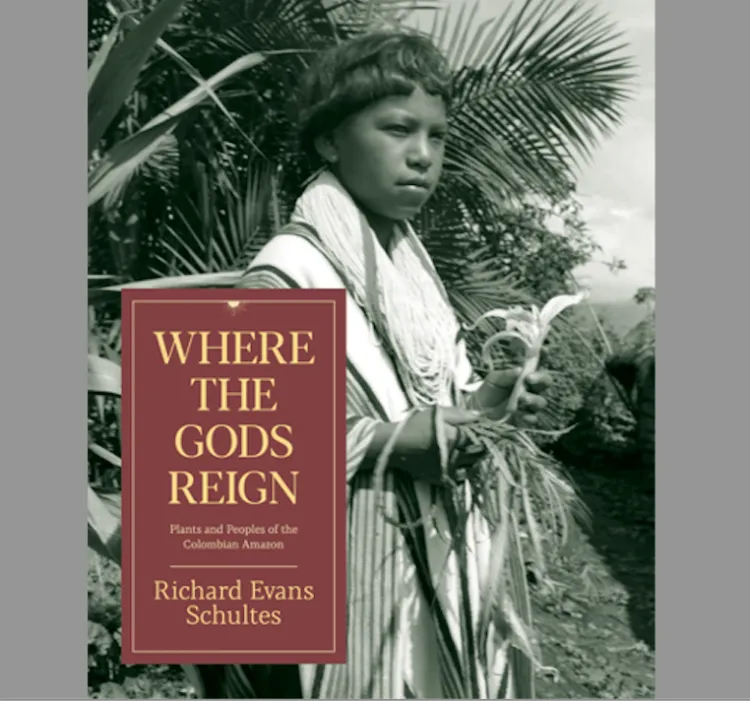

Ethnobotany as an area of study serves many purposes. In the more modern era, Richard Evan Schultes, sometimes referred to as the “father of modern ethnobotany,” is known for studying uses of plants by indigenous peoples, mostly in the Americas. He studied several hallucinogenic drugs, some of which now have roles in modern medicine, and was one of few ethnobotanists who fostered a mutual relationship with the indigenous peoples he was learning and gathering specimens from. He made an effort to learn the languages of the native people he stayed with, and gathered information about plants directly from tribal leaders. Schultes spent over a decade living in the Colombian Amazon from 1941 to 1953, gathering over 24,000 specimens of plants, and is hailed as one of the first to recognize that the people and cultures of the Amazonian rainforests were threatened just as much as the forests themselves.

"Where the Gods Reign" is one of Richard Evans Schultes’s publications about his time spent living in the Colombian Amazon. It is available on the third floor of the Howe Library, along with other publications by Schultes.

As shown above, the University of Vermont is home to countless resources related to ethnobotany and its history that are waiting to be utilized. There are books available in all four of the institution’s libraries; some are available for check out, such as in the Howe Library, and some that can be requested for in-library viewing, as in the Silver Special Collections Library. The Pringle Herbarium is also a comprehensive resource on all things plants; located in Jeffords Hall with over 360,000 mounted specimens of plants and fungi, it is the second largest herbarium collection in the northeastern United States. All of these resources, and more, are available to all students who may be researching the history of plant use, ethnobotany, or are just interested in learning more on the subject.

This is just one example of a modern herbal that is housed in the Pringle Herbarium’s Library. It contains over 1,000 species of edible wild plants from Eastern North America.

By Kylie Roth

References

Ames, O. (n.d.). The Amazonian Travels of Richard Evans Schultes. Amazon Conservation Team. Retrieved November 15, 2024, from https://www.amazonteam.org/maps/schultes/en/

History of Ethnobotany. (n.d.). Bionity. Retrieved November 15, 2024, from https://www.bionity.com/en/encyclopedia/Ethnobotany.html

Morand, S., & Lajaunie, C. (2017). Animal and Human Pharmacopoeias. In S. Morand & C. Lajaunie, Biodiversity and Health: Linking Life, Ecosystems and Societies (pp. 103-117). Elsevier Science. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-1-78548-115-4.50007-X

Petrovska, B. B. (2012). Historical Review of Medicinal Plants’ usage. Pharmacognosy Reviews, 6(11), 1-5. https://doi.org/10.4103/0973-7847.95849

Plotkin, M. J. (2022, August 10). Richard Evans Schultes. Harvard Magazine. Retrieved November 15, 2024, from https://www.harvardmagazine.com/2022/06/vita-richard-evans-schultes

What is ethnobotany? (n.d.). Botanical Dimensions. Retrieved November 15, 2024, from https://botanicaldimensions.org/what-is-ethnobotany/