Published November, 2025

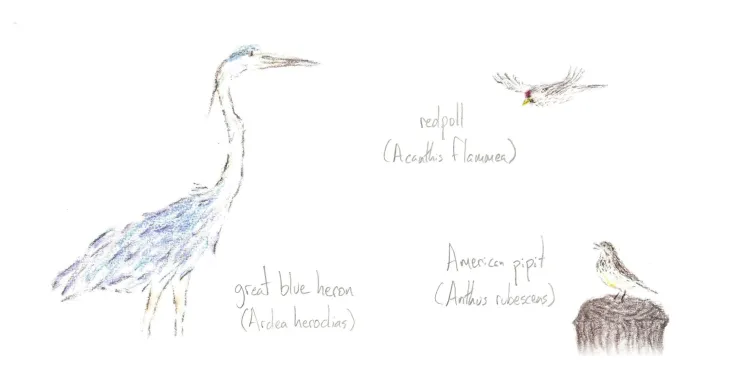

In Greek Mythology for Botanists & Birders (crowspath.org/mythology), I’ve set out to rewrite Greek and Roman myths that feature heroes, gods, and tragic figures whose names are found scattered throughout our scientific lexicon. Here is a lesser-known story from Antoninus Liberalis’s Metamorphoses. Several scientific names (e.g. pipits: Anthus and redpolls: Acanthis) are taken directly from this myth.

* * *

Autonous had always desired well in excess of both his needs and abilities. And his union to Hippodamia1 (hippo: horse, damazein: to tame) perhaps presaged that his desires would be singularly channeled towards turning the stubborn mastic2 shrubs of his hill farm into a herd of horses.

On the night of their wedding, Autonous’s father, Melaneus, gifted the newlyweds a small herd of horses to help beat back the onslaught of unruly plants encroaching on their small home. When they awoke the next morning to a golden dawn light, the newlyweds walked the land, hands entwined, Hippodamia imagining their children learning to tend the groves of olives, fields of barley, rose hedges, and a thriving vineyard. But Autonous imagined only a throng of horses powerful and glorious enough to rival Poseidon’s hippocampi.3

Their herd of children grew quickly in those first few years, Hippodamia giving birth to four healthy boys—Anthus, Erodius, Schoeneus, and Acanthus—and their sister, Acanthis. The children grew up tall and strong, with Hippodamia’s bountiful crops filling their bellies. Erodius in particular took a fondness to the horses, and, as Melaneus intended, under Erodius’s care the horses tamed the shrubby hills.

Autonous, however, couldn’t be bothered with the drudgery of farming, and when he expended any energy at all, he set it only to acquiring new horses. The small herd his father had given them doubled in number and, like a plague of locusts, their callous hooves and restless jaws overtaxed the land, stomping and chewing the nettles and dandelions down to the bone.

So it was that the land, tired of too many horses, was soon barren of color. The vacant yellow eyes of the sad horses looked longingly at the green gardens on the other side of their fences, and they pestered at the split rails. Erodius did his best to mend the holes, but he was of his father and so, with time, the fence started to rot.

On one bleak morning in August,4 Anthus, the eldest of the children, awoke to find Helios late to ride his chariot into the sky. An ashen pallor loomed over the late-summer farm as the frustrated Anthus made his way to the barren meadows where the horses were supposed to be grazing. The static charge of the impending storm prickled his arms. He reached the edge of the pasture just as Zeus’s clamorous blows echoed across the land, unleashing a lasting rain that soaked the hillside. The pasture had been abused by too many horses over too many years and the soil washed away under the heavy onslaught of rain.5

Anthus wiped the rain from his brow and strained through the darkness to see if the horses were still in their pen. Nothing but yet another hole, and surely the horses would be out stealing grapes. He turned back to the barn for tools to mend the wound in the fence and to see if he could find and wrangle the horses.

But at his second step, he felt the presence of a penetrating stare through the thick rain. He looked up and saw a frightful line of yellowed eyes glowering with fear and hunger. His heart was angered by the horses for eating the crops, by his father for neglecting the care of both his family and the horses, and by Erodius for these dilapidated fences. He knelt slowly down, grabbed a crooked branch, and set out to drive the horses back into their barren pasture.

The horses turned to flee, but then a fierce hunger beset them and they spun around to face Anthus. They were caught in that long moment until a flash of lightning broke the silence, and with a great cry the horses broke into a gallop charging at the startled Anthus. He had only a heartbeat of realization before he started to run. He was too slow, and the ravenous horses fell upon him, tearing flesh from bone.6 His screams for mercy echoed up to the heavens and down to his house.

Autonous heard the cries of anguish and reluctantly ascended the hill. He was quickly overtaken by his wife, Hippodamia, who ran to save her son. Both had grown weak from years of failing crops, but only the cowardly Autonous feared the stinging bite of the horses while his wife fought ferociously to save her son. And she would have kept on fighting until the horses took her own life as well, had the gods not looked down upon the family with pity.

Zeus and Apollo were first to hear the cries of Anthus and swept down from the tumultuous skies. Together they drove Poseidon’s storm and the frenzied horses back. The gods of thunder and healing walked into the meadow, seeing a desperate, terrified family afraid of the horses, of the skies, of the land. In a rare moment of empathy, the gods turned each into a bird.

Autonous, who in cowardice turned away from helping his son, became a quail, always timid, always scurrying away at the faintest scent of danger.

His wife, Hippodamia, took the form of a lark, her small head adorned by Apollo with a crest to honor her courage in attacking the horses.

Acanthis, Autonous’s fair daughter, would mourn her family’s tragic undoing in those aggrieved fields of thistle and reed as a thistle finch.

Erodius is said to have become a heron.7

And lastly, the poor Anthus, who would forever be haunted by those horses, was set to the skies in the plumage of a pipit. And to this day, the bird strikes off at the sight of a horse, fleeing to safety while whistling an inculpatory neighing sound.

1 Hippodamia is the genus of North American lady beetles. In The Iliad, Homer frequently refers to Hector as Hippodamia, the breaker of horses.

2 Mastic means resinous, particularly in reference to the mastic tree, Pistacia lentiscus. The resin was used in Ancient Greece as a chewing gum. From this we get masticate (to chew), mast (the edible nuts of beech, oak, etc.), and masseter (the muscle that clenches the jaw and is used for chewing).

3 Poseidon, god of the horses, had a chariot pulled by the hippocampi (half horse, half fish); Hippocampus is the genus for seahorses; the hippocampus is a seahorse-shaped ridge on the temporal lobe of the human brain.

4 Augustus Caesar named this month after himself (his forebear, Julius, had already claimed July).

5 While it’s possible that “erode” comes from Erodius’s name, it is more likely the link goes the other way (roder is the Latin for “to gnaw,” as in rodent).

6 Horses, like other grazers, are opportunistic omnivores. Heracles’s eighth task was to steal the man-eating Mares of Diomedes (Diomedeidae is also the family for albatrosses).

7 Herons are in the genus Ardea, possibly from Erodius.

About the Author

Teage O'Connor is a naturalist, educator, and philhellene. As founding and Executive Director of Crow's Path, he works to find creative ways of connecting people to wild-ness.