Edible Plants

From the ground to your dinner plate!

While humans have been using plants as medicines and religious or spiritual symbols for tens of thousands of years, our first association with plants going all the way back to the dawn of our species 300,000 years ago, was eating them. Our earliest human ancestors survived on edible nuts, seeds, and other plant material long before we learned to hunt. It wasn’t until only 12,000 years ago that humans would invent agriculture, creating the first sedentary civilizations; as people could now control production of their food and stay where they were instead of following the food where it was going, the first seeds of our modern industrialised society were born. Some of those first-developed agricultural crops are still the most important crops in the modern day and comprise a large part of the human diet.

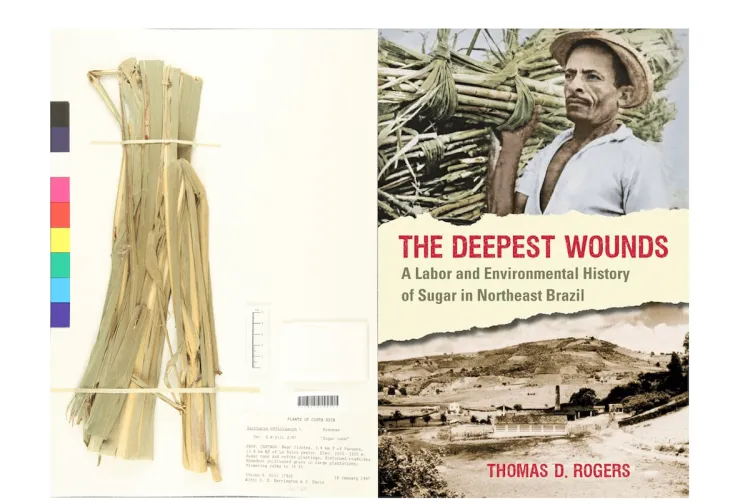

It personally shocked me to learn that the most highly produced cultivated crop in the world is not a type of cereal or grain, but in fact sugarcane. The USDA estimates that around 180 million metric tonnes of sugarcane (Saccharum officinarum) are produced globally each year, with over 25% of that production coming solely from Brazil. The sugar that comes from the processing of sugarcane is used not only as the sweetener that we are accustomed to being such a large part of our diet, but is also now being converted into ethanol, a biofuel. Sugarcane is originally native to New Guinea, and was domesticated there sometime between 8,000 and 10,000 years ago before going on to spread into Asia and Oceania. It would later be spread to North Africa, Europe, and the Middle East, and is today primarily cultivated in Brazil, India, and China.

The history of sugarcane production is intimately tied with the use of slave labor in the Americas in the 18th and 19th centuries. As demand for the “white gold” increased, so did the demand for people to do the incredibly laborious work of tending to sugarcane plantations. More about this topic can be found in several books in the Howe Library detailing the extensive history and repercussions of the global explosion of sugarcane production. One of these is The History of Sugar by Noël Deerr, and another is The deepest wounds : a labor and environmental history of sugar in Northeast Brazil by Thomas Rogers.

On the left is a specimen of "Saccharum officinarum" from the Pringle Herbarium collected in 1987 from Costa Rica. The stalks or stem shown in the specimen are the part of the plant used to make sugar. After harvest, the stalks are crushed and the juice from them is extracted, purified, and crystalized into the white sugar we use. On the right is "The deepest wounds : a labor and environmental history of sugar in Northeast Brazil" by Thomas Rogers available in the Howe Library. Rogers’s work spans four centuries of social and environmental changes in the sugarcane industry in Brazil.

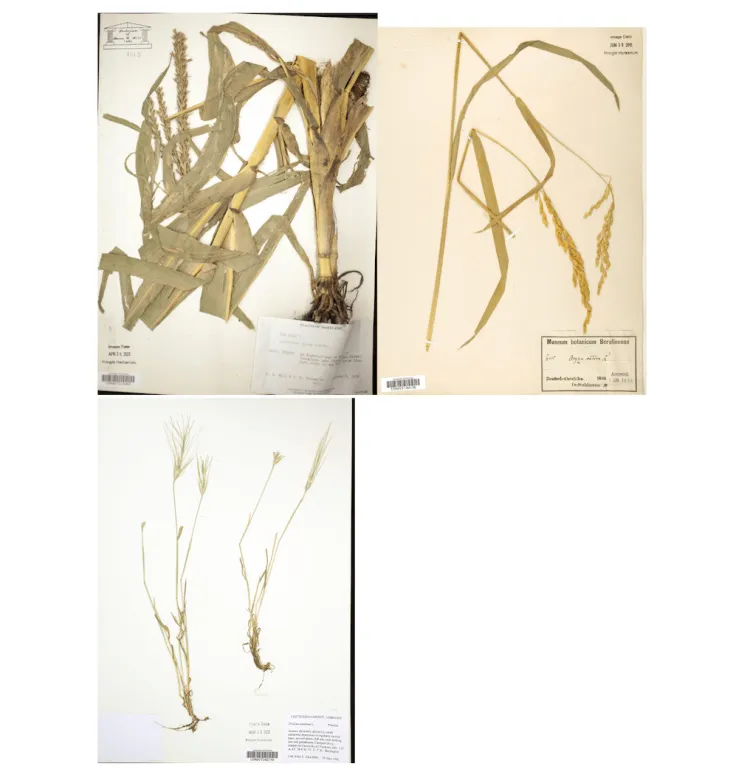

After sugarcane, the most highly cultivated crops are also the most highly consumed by humans. These are corn (Zea mays), rice (Oryza sativa), wheat (Triticum), potato (Solanum tuberosum), and cassava (Manihot esculenta). Rice, maize, and wheat alone makeup 51% of the world’s caloric intake, and are all from the same botanical family (Poaceae, the grass family). Maize originates from the lowlands of western Mexico, and was domesticated about 9,000 years ago and is now the most produced grain in the world, with the largest producer of the crop being the United States, followed by China. The majority of the production in these countries does not feed our populations, however, and is primarily used to feed livestock and create ethanol fuel.

The rice we eat today was first domesticated between 8,000 and 13,000 years ago from its native range in the Yangtze River valley in China or the Ganges River valley in India. China and India are still the main producers of rice today, and Asia consumes 90% of rice grown globally. Since rice is so vital to the populations of many Asian countries, it is one of the most protected food commodities in world trade. However, the crop is not a substantial source of vitamins and minerals (though it is an excellent source of necessary carbohydrates and some essential amino acids), leading to deficiencies in many people that subsist on rice, and has invoked a movement to find ways to fortify rice with these necessary micronutrients.

These three specimens are found in the Pringle Herbarium; from left to right are corn ("Zea mays"), rice ("Oryza sativa"), and wheat ("Triticum"). All are important grain crops in the Poaceae (grass) family.

Cassava (Manihot esculenta) is a species of tuber native to South America, and was domesticated in the Southwestern Amazon of Brazil and Bolivia between 8,000 and 10,000 years ago. Today, it is consumed by over 800 million people worldwide, and is a primary staple food for over 500 million people in Africa, and about 160 million tons of the crop is produced yearly. Despite its popularity, cassava can be very poisonous if not processed correctly. The plant contains chemicals that release small amounts of cyanide when consumed raw, which is why soaking, cooking, and processing the tuber before consumption is so important. The plant also has a very short shelf life post-harvest of only two days before it starts to rot, which is why it is often processed into flour quickly after harvest to increase the longevity of the product. To process the cassava tuber, it is first grated or mashed into a pulp, and the liquid containing the poisonous chemicals is squeezed out of the pulp. It can then be fermented, roasted, or dried and milled into a naturally gluten-free flour, often mixed with water to create a dough called fufu.

These are images from the Fleming Museum of Art on the UVM campus of tools that are currently on display. They are all tools used for processing cassava ("Manihot esculenta") that come from the Waiwai people, an Amazonian tribe. From left to right, the objects are a cassava grating board to grate the tubers after harvesting, a squeezer used to squeeze the poisonous liquid out of the pulp, and a sifter used to separate out the flour.

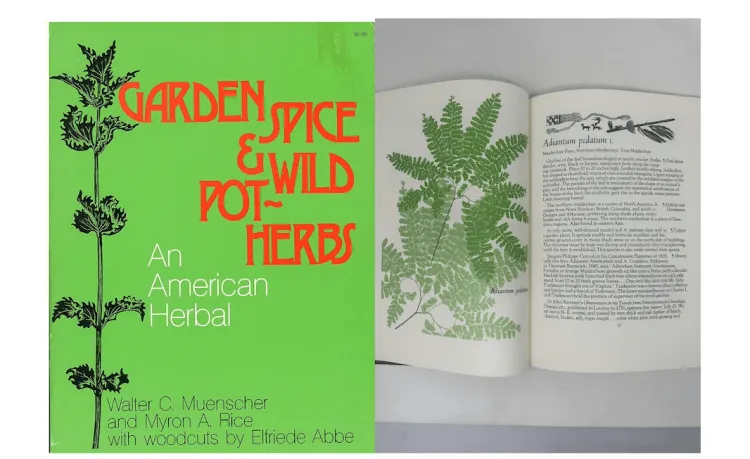

The Pringle Herbarium’s archival collection is also home to a number of books and artworks by Elfreide Abbe, an artist and botanical illustrator who called Vermont home in her retirement, that were donated to UVM. Some of the books in the collections are herbals, which describe the culinary and medicinal uses of plants, and are now in the Silver Special Collections Library, including a copy of The Fern Herbal: Including the Ferns, the Horsetails, and the Club Mosses, which was published in Vermont in 1982. This was one of only 150 copies produced, as the illustrations were woodcuts and the books were published on Abbe’s personal press. Another book housed in the Silver Special Collections Library on the theme of edible plants is Garden spice and wild pot-herbs which was written by Walter Conrad Leopold in 1978, which also features woodcut illustrations of dozens of plants by Elfreide Abbe. Secondary copies of these books are also kept in the archive collection of the Pringle Herbarium, along with other works of Elfriede Abbe.

These are the copies of the books by Elfriede Abbe kept in the Pringle Herbarium’s archive. Both of these books were limited edition copies. They both include wood cut images and descriptions of herbs and ferns, and how they can be used medicinally or in cooking.

These industrial crops are, of course, vital to the way most of the human population currently feeds and employs itself, and conducts business globally, but there are so many thousands more plants that are consumed by different cultures on a much smaller scale. Many cultivated crops that are not so widely produced and consumed across the globe are still very important historically or currently in smaller, more local communities. Some examples of plants like these are talked about in Food Plants of the Sonoran Desert by Wendy Hodgson, and include the sagauro cactus (Carnegiea gigantea), prickly-pear (Opuntia Velutina), and Yucca plants. Some of the plants native to smaller land areas and important to those cultures have still managed to become highly commercialized, such as seeds of the chia plant (Salvia hispanica) and Agave, both of which Hodgson covers.

These are two examples of resources on culturally important food plants in smaller communities that are available at UVM. Both books detail hundreds of plants used by Indigenous American peoples, and how they were harvested, prepared, and eaten traditionally.

Agave is native to Mexico, Central America, South America, and the Caribbean Islands. It is a succulent with many uses, but is commonly known for its role in making syrups and beverages—including tequila. Agave americana has also been known as the “century plant” and the history of its use goes all the way back to the Aztec people in Mesoamerica, where it was used to create a fermented beverage; its fibers were also employed for textiles. A lesser-known plant also from the southwestern United States and Mexico is ocotillo (Fouquieria splendens). This desert-dwelling plant’s name means “little torch” in Spanish, a result of its bright red flowers. Historically the plant’s fruits and flowers were eaten by the Cahuilla, or were soaked in water to brew a tea.

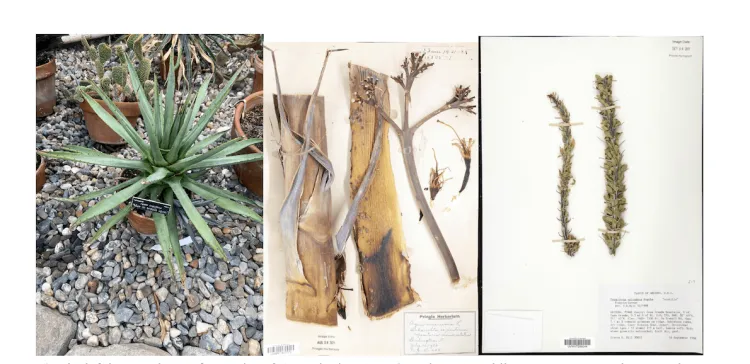

On the left is a specimen of a species of "Agave" in the UVM Greenhouse’s public conservatory. In the center is a specimen of "Agave americana" collected in 1938. On the right is a specimen of Ocotillo ("Fouquieria splendens") collected in 1998 in the Casa Grande Mountains of Arizona. Both herbarium specimens are found in the Pringle Herbarium, along with thousands of other specimens of edible plants.

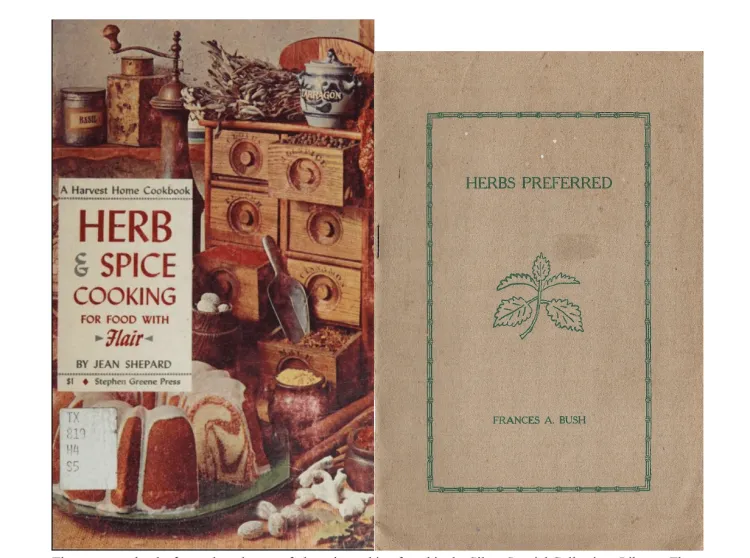

Seeing as plants are so important to our diets and daily lives, there is no shortage of research one can do on what plants people eat (or have eaten historically) or why we eat the things we do. UVM houses an incredible amount of resources on edible plants, both those used in the present and those of the past. Books and journals on culturally important foods, the rise of mass produced crops, the social effects of food plants, and more can be found in all of UVM’s libraries or digital collections. The greenhouse and Pringle Herbarium are home to many more physical resources of edible plants, and can supplement research done elsewhere. With so much learning to do, an easy place to start, for example, might be something as simple as a cookbook that focuses on how plants can add to your meals. The two pictured below are found in the Silver Special Collections Library.

These are two books focused on the use of plants in cooking found in the Silver Special Collections Library. These books are both from the mid 20th century, and tie the use of plants into more modern and practical uses for a Western audience.

By Kylie Roth

References

Ates, A. M. (2023). Feed Grains Sector at a Glance. USDA Economic Research Service. Retrieved December 1, 2024, from https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/crops/corn-and-other-feed-grains/feed-grains-sector-at-a-glance/#:~:text=On%20average%2C%20U.S…

Busam, S. (2024). Cassava: A Promising Example of Climate Resilient Crops that Minimize Waste and Maximize Value. Upcycled Foods Lab. Retrieved December 1, 2024, from https://upcycledfoods.com/cassava-a-promising-example-of-climate-resilient-crops-that-minimize-waste-and-maximize-value/

Clarke, M. A., & Singh, R. P. (2024). Sugar - Cane, Refining, Sweetener. Britannica. Retrieved December 1, 2024, from https://www.britannica.com/science/sugar-chemical-compound/Cane-sugar

Davis, S. C., & Ortiz-Cano, H. G. (2023). Lessons from the history of Agave: ecological and cultural context for valuation of CAM. Annals of Botany, 132(4), 819-833. https://doi.org/10.1093/aob/mcad072

Foreign Agricultural Service. (n.d.). Production - Sugar. Retrieved December 1, 2024, from https://fas.usda.gov/data/production/commodity/0612000

Hermsen, E. J. (2023). History of sugarcane. Earth@Home. Retrieved December 1, 2024, from https://evolution.earthathome.org/grasses/andropogoneae/sugarcane-history/#:~:text=Sugarcane%20is%20in%20the%20genus,plant%20ha…

Hurst, K. K. (2019). The History and Domestication of Cassava. ThoughtCo. Retrieved December 1, 2024, from https://www.thoughtco.com/cassava-manioc-domestication-170321

Moore, L. M., & Lawrence, J. H. (2003). Cassava. NRCS Plant Guide. Retrieved December 1, 2024, from https://plants.usda.gov/DocumentLibrary/plantguide/pdf/pg_maes.pdf

Muhammad, K. G. (2019). The Barbaric History of Sugar in America. The New York Times Magazine. Retrieved December 1, 2024, from https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2019/08/14/magazine/sugar-slave-trade-slavery.html

Pobiner, B. (2016). Meat-Eating Among the Earliest Humans. American Scientist. Retrieved December 1, 2024, from https://www.americanscientist.org/article/meat-eating-among-the-earliest-humans

République française. (n.d.). Sugarcane. CIRAD. Retrieved December 1, 2023, from https://www.cirad.fr/en/our-activities-our-impact/tropical-value-chains/sugarcane/plant-and-uses#:~:text=Sugarcane%20is%20a%20g…

Texas Beyond History. (n.d.). Ocotillo, Devil’s Walking Stick. Retrieved December 1, 2024, from https://www.texasbeyondhistory.net/trans-p/nature/images/ocotillo.html

University College London. (n.d.). Debating the Origins of Rice. Retrieved December 1, 2024, from https://www.ucl.ac.uk/rice/history-rice/debating-origins-rice