Step into the emerald embrace of Northeast India, a global biodiversity hotspot teeming with life. Among the lush greenery, the western hoolock gibbon, India’s only wild ape, swings through the trees. Their concert songs, a symphony of the forest, once echoed across these densely forested hills. But lately, a hush has fallen, a silence where vibrant calls once resonated. The forests, the very lifeline of these incredible creatures, are shrinking, and the interconnected lives of the local communities are changing with them.

Figure 2: A house in the mountains (PC: Varun R. Goswami, Conservation Initiatives)

The Foundation: A Deep Connection through Forests

For generations, tribal communities living in Meghalaya and Nagaland, who share the forests with these tender beasts, have maintained a profound connection with the animals and their forests. The forests serve as the cornerstone of food security in these communities.

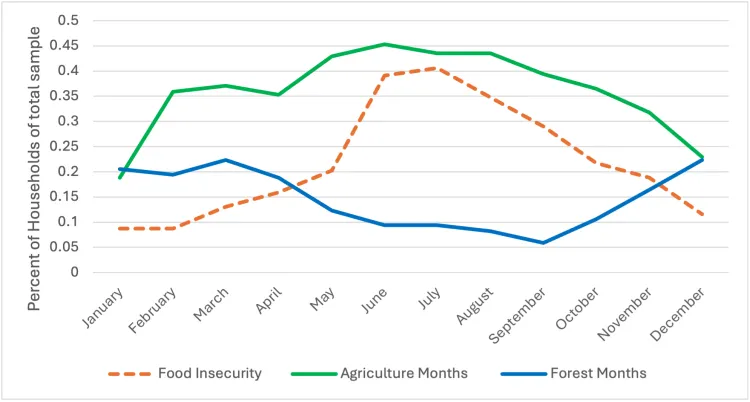

Seasonal Rhythms of Food Security: During the monsoon, when heavy rains make agricultural work the priority, access to the forest becomes difficult. This often coincides with months of increased food insecurity (Figure 3). As the monsoon season eases, the forest once again becomes a vital source, providing not just sustenance but also dietary diversity through medicinal plants, leafy greens, roots, and even bush meat.

Beyond Sustenance: A Holistic Connection: The relationship extends beyond mere resource extraction. These forests provide crucial social, psychic, and identity benefits, highlighting the deep integration of these communities with their natural surroundings.

Figure notes – Data derived from a previous project on the community in 2021. Y axis refers to the percent of households in the sample who – 1. Recalled facing any food shortages in each month (x -axis) pre-covid (orange dashed line), 2. Reported agricultural activity in a particular month (green line) and 3. Reported visiting the forest for an activity in a month (blue line).

Why Protect the Hoolock?

Unpacking the Community's Conservation Ethos

There is growing interest within the Nagaland and Meghalaya communities to protect forests and their inhabitants, including the western hoolock gibbon. This is driven by a fascinating mix of cultural, practical, and emotional factors.

A Deep Sense of Kinship and Loss: The dwindling calls of the gibbons evoke a profound sense of loneliness, as if a familiar presence has vanished from their shared space. Many communities revere these animals as kin, experiencing their loss on a spiritual level.

Sympathy for a Harmless Neighbor: Unlike some other wildlife, gibbons do not pose a threat to crops, fostering a sense of sympathy for their plight as innocent victims of habitat loss.

Shift away from Hunting: There is some condemnation of poaching and hunting, which is viewed as a practice no longer in tune with the legal and moral framework of today.

A Generational Shift in Values: A significant divergence exists between generations. While older generations may have engaged in ritualistic hunting, younger community members largely view such practices as old-fashioned.

A Catalyst for Change: Factors Threatening the Forest and its Inhabitants

While communities hold deep reverence for the forests and their inhabitants, their actions, driven by evolving circumstances, have contributed to the decline of gibbon populations and their habitat.

The Efficiency of Modern Hunting: The shift from traditional hunting tools to more efficient guns and rifles has increased the impact of hunting, even if not primarily for food.

The Push for Economic Development: Increasing economic aspirations, particularly the desire for better education, can create pressure to exploit forest resources like timber, especially in community-owned forests lacking formal protection.

The Vicious Cycle of Unsustainable Agriculture: Climate change and the adoption of monocropping have led to soil degradation and increased pest vulnerability. This has ironically forced farmers to rely more heavily on shorter cycles of slash-and-burn agriculture and shift to monoculture cash-crop plantations due to declining productivity, further accelerating deforestation.

The Erosion of Traditional Land Management: The rising demand for resources and cash has disrupted traditional practices of leaving land fallow for forest regeneration, hindering the natural recovery of agricultural areas.

Photos from the Field

Fig. 3 Slash and Burn Agriculture in the Northeast of India (PC: Pragyan Sharma, Conservation Initiatives)

Fig. 4 Sand Mining in the Northeast of India (PC: Anaka Aiyar, University of Vermont)

Fig. 5: Dependence on Firewood for Fuel Northeast of India (PC: Divya Vasudev, Conservation Initiatives)

A site for change: Socio-Ecological Agency

In our research we shine a light on the socio-ecological agency (SEA) of nature-dependent communities, positioning them as the primary drivers of change, and external factors such as NGOs as crucial supporters. This perspective acknowledges the intricate social and ecological dynamics within these communities, moving beyond simplistic portrayals of harmony or conflict with nature. SEA has two aspects.

External Supporters of Change: Mediated Agency: While SEA originates within the community, external actors can play a supportive role through mediated agency. Scientists and institutions are more likely to be effective when their observations align with the lived experiences of community members. Humility and a mutual learning mindset are crucial for successful engagement. External support will also be more successful if it is able to balance conservation with meeting the community’s basic needs.

Internal Drivers of Change: Collective Agency: Change also emerges from within the community through collective agency. This involves negotiations and evolving values among community members. Intergenerational differences in perspectives on conservation and livelihood aspirations can drive new approaches. Traditional institutions like village councils serve as vital platforms for deliberative democracy, allowing communities to collectively decide on the direction and pace of change, balancing tradition with innovation. Even mechanisms like mythmaking and identify building play a role in shaping sustainable interactions with nature.

A More Empowering Perspective:

Research from this project offers a powerful and nuanced understanding of how nature-dependent communities are adapting to environmental challenges. It recognizes the inherent agency and capacity of communities for transformative change, while also acknowledging heterogeneity amongst communities and challenges in acting for conservation. This is particularly important in the region, as lands and forests are largely managed by local communities. By understanding the "why" and "how" behind their actions, we can develop more effective and respectful collaborations that support their efforts to sustain both their way of life and the natural world around them.