As the gardening season draws to a close, now is the ideal time to set yourself up for success next year. Assessing the health of your soil this fall will result in a solid foundation for your plants by spring.

Start by conducting a soil test (https://go.uvm.edu/soiltest) for any vegetable and berry gardens, plus additional, separate tests for areas with different growing conditions such as perennial beds, fruit trees, and lawn.

The tests will be returned to you showing the value of Phosphorus (P), Potassium (K), and Magnesium (Mg) present in your soil sample, in addition to many other essential nutrients. It will also identify the pH level of the sample(s) tested. Lastly, it will show the percentage of soil organic matter and the Cation Exchange Capacity (CEC) percent, which is the soil’s ability to absorb and deliver positively charged nutrients.

A pH of 6 to 7 is optimal for most crops. If the pH is below 5.5 (acidic) or above 7 (alkaline), the chemical conditions in the soil may prevent the plants from properly taking up the nutrients that are present. An exception to this is plants like blueberries and rhododendron which thrive in acidic soil.

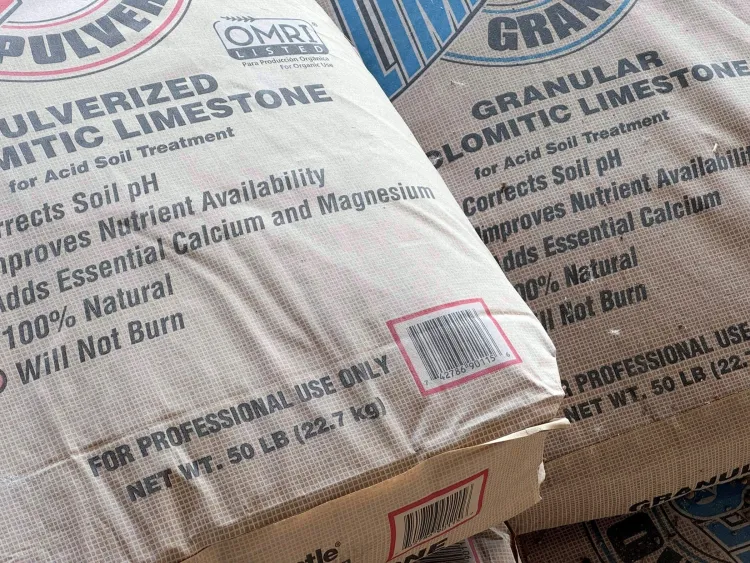

The addition of lime will increase the pH in soil that is too acidic. Look for calcite, a high-calcium form of lime, to use on soil without a magnesium deficiency. If magnesium is low, however, choose dolomite, which will boost magnesium at the same time as the lime lowers the soil ph. If your soil test recommends more than 100 pounds of lime per 1,000 square feet, splitting the application between fall and spring is recommended.

Wood ash can be used in place of lime to increase the pH of your soil. Use about 2 to 3 times more ash by weight than lime.

For soil with too high a pH value, elemental sulfur is employed to reduce it.

To address soil nutrient deficiencies, pH is often the best place to start because some soil nutrients become unavailable to plants when the pH is off.

In terms of chemical and natural fertilizers, gardeners, like farmers, should be careful to apply only the amount of nutrients needed for optimal plant growth to avoid excessive nutrients that may inadvertently end up in ground and surface waters. In fact, a 2012 Vermont law restricts the application of phosphorus (P) fertilizers to lawns unless a soil test indicates their soils are deficient in P or if you are establishing a new lawn. Nitrogen (N) fertilizer applications are also prohibited to lawns.

While fall application of some slow-release natural fertilizers may give them the necessary time for microorganisms to break them down into accessible nutrients for your plants, it is best to wait for spring for most applications, especially if applied to bare soil. The same goes for most bagged composts that can be high in P if made from animal manures.

Cover crops, on the other hand, are a great way to add nutrients and improve soil structure. While it is late in the season for planting, winter rye, triticale, hairy vetch, winter wheat, winter peas, fava beans, and crimson clover are fairly winter hearty once germinated.

Put mulch over bare soil to protect it from erosion, help it retain moisture, reduce leaching of nutrients, build organic matter, and suppress weeds. Organic mulches such as chopped tree leaves, herbicide-free grass clippings, straw, wood bark, and wood chips are broken down by microbes, releasing a moderate amount of nutrients into your soil in the process. Mulch your acid-loving blueberries with wood chips, pine needles and bark fines, and/or aged sawdust.

Should you have questions about your soil test results or need assistance choosing the right amendments, contact the EMG helpline at https://go.uvm.edu/gardenhelpline.