Mount Mansfield, Vermont’s highest peak, has long been a site for research and monitoring. In 1859, the University of Vermont purchased both the summit and 400 acres of its ridgeline for its conservation value and potential to support research and education. In doing so, UVM became a pioneer in the land conservation movement as an action like this was unprecedented for its time.

With its unique geology, long monitoring history, rare flora and fauna, and elevated precipitation, the mountain serves as a crucial living laboratory for a wide range of interdisciplinary studies. It has been formally designated as an intensive long-term monitoring site by the state of Vermont. Mount Mansfield has a weather and snow monitoring record dating back to the 1950s, which includes the iconic Mount Mansfield snow stake that provides a multi-decadal record of snow variability on the mountain.

Fall 2025 marked a new milestone on the mountain – a quarter century of hydrologic monitoring at Ranch Brook and West Branch – two headwater streams draining the eastern flanks of Mount Mansfield. Initiated in the fall of 2000 through support of the Vermont Monitoring Cooperative, now the regional Forest Ecosystem Monitoring Cooperative, and the Lintilhac Foundation, the Mansfield paired watershed study aimed to develop infrastructure for monitoring high elevation hydrology in the state.

The study’s lead investigator, Dr. Jamie Shanley, a hydrologist with the U.S. Geological Survey and UVM Rubenstein School adjunct faculty member, identified the streams and their watersheds as ideal for addressing mounting alpine development concerns in the region. At that time, new UVM faculty member, Dr. Beverley Wemple, joined the project to contribute expertise in forest hydrology. “Initiation of this study in the early 2000’s provided a unique opportunity to expand water monitoring and understand the impacts of ski area development,” says Wemple, now Director of UVM’s Water Resources Institute.

Two streamflow monitoring stations were established on streams of the eastern slopes of Mount Mansfield. With their implementation, Shanley and Wemple established a baseline to assess changes associated with mountain resort development and a shifting climate. This original investment helps guide the state on water management issues today.

Warmer winters are driving snowpack declines

Existing monitoring in the watersheds surrounding Mount Mansfield is integral to understanding how warmer winters are driving a declining snowpack.

Using historical data, UVM researchers have been able to determine how the snowpack has changed in a high-elevation region of the Northeast and how this drives seasonal runoff. A recent study leveraging this long-term monitoring looks at how a warming climate threatens the timing and amount of future water delivery.

Why should we care about the snowpack? According to Kate Hale, the study’s lead author and a former UVM post-doctoral researcher, “approximately 1/6 of the global population relies on snowpack and glacier runoff as their primary water resource.”

However, climate change is altering the winter season, creating a shorter snow season on average – with a later onset and an earlier snow melt. In the northeast, there are only scarce observations with very little research on this phenomenon.

Mount Mansfield is one of the snowiest spots in the northeastern USA. About 25% of annual precipitation falls as snow at lower elevations and up to 40% near the summit, based upon data gathered at the USGS gages and the National Weather Service (NWS) snow stake.

The snow stake was established on Mount Mansfield’s summit in 1954 and is monitored daily by the NWS. The stake is read for depth and not water equivalent, but it is a reliable indicator of snowpack magnitude.

By leveraging these multi-decade records of snow depth and runoff, and utilizing funding from the Cooperative Institute for Research to Operations in Hydrology (CIROH), researchers are able to uncover long-term trends in the northeastern snowpack.

They have found that the snow season has declined in duration by almost 3 weeks since 1965, as snowpack onset occurs later in the fall months, its disappearance occurs earlier in spring months, and winter rain-on-snow and rainfall events have increased.

In response, winter runoff has been increasing.

Years with more winter runoff correspond to increased winter temperatures, a smaller snowpack, and more rain-on-snow events. This steady decline in the regional snowpack impacts downstream water resources, with the risk of more mid-winter flooding and summer drought.

The study demonstrates that Mount Mansfield is crucial in understanding significant relationships between the Northeast snowpack and downstream hydrology, addressing a knowledge gap for an understudied snow-water system.

The Summit to Shore (S2S) Network

The Northeast mountains are highly sensitive to temperature changes, driving flooding, rain-on-snow events, and water supply availability. However, there is a lack of distributed weather data here, particularly in the winter. The Summit to Shore (S2S) Environmental Monitoring Network, originally funded by the US Army Corps of Engineers Cold Regions Research and Engineering Laboratory (CRREL), is an observation network looking to change that.

Dr. Arne Bomblies, the principal investigator of the S2S project, is working to better understand snowpack characteristics, comparing them with aerial imagery. Bomblies and his team are working to improve monitoring and modeling of snow at multiple elevations, aspects, and canopy conditions in Vermont.

The S2S Network has 22 weather and snow monitoring stations along an elevational gradient spanning from Lake Champlain, up to Mount Mansfield, and across to the Northeast Kingdom, providing key snow and meteorological instrumentation where the most rain and snowfall occur, and that has the potential to lead to flooding events downstream.

Most of the network's weather stations are around Mount Mansfield, with a cluster in the Ranch Brook watershed. From 2022-2025, the UVM team has used the network to document how snowpack characteristics depend on meteorological and environmental factors. Stowe Mountain Resort / Vail Resorts have been key in-kind partners supporting access to the mountain during both the summer and winter months to service equipment.

The siting of these stations leverages long-term monitoring that exists on Mount Mansfield and its watersheds, among other UVM lands, such as the Mount Mansfield Natural Area, Jericho Research Forest, and Proctor Maple Research Center.

This research is especially important for a region that sees rapid transformations in the winter. As the risk of rain-on-snow flooding increases, this project will allow scientists to look at the changing conditions that are driving this phenomenon.

Links between the forest canopy and snow depth

How do forests affect snow? Forests have the potential to alter the snowpack by intercepting precipitation, shading it from sunlight and melting, buffering it from the wind, and emitting long wave radiation, producing thaw circles that you may notice around the bases of trees.

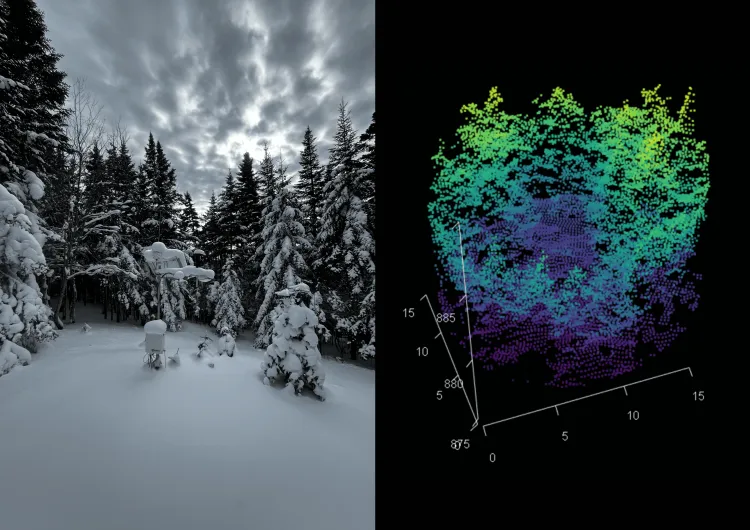

Jacob Ladue, a UVM graduate student in Civil Engineering, is working on modeling snowpack variability from forest metrics. His work demonstrates how forest canopies impact snow depth.

Ladue is utilizing Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR), a remote sensing method that uses laser pulses to measure distances to the Earth to characterize canopies. Coupled with machine learning, this allows him to predict snow depth change from weather and site characteristics like the forest canopy.

Ladue’s research leverages his undergraduate training in UVM’s Forestry program with his skill set gained in his dual undergraduate degree in Civil & Environmental Engineering.

“This work highlights the power of emerging digital forestry tools for informing adaptive strategies that can sustain threatened ecosystems, species, and processes into the future,” says Tony D’Amato, the Director of the Foresty Program and Ladue’s advisor during his undergraduate degree. “That includes how we might encourage specific forest conditions to maintain and enhance snowpack in a warming environment.”

Ladue’s analysis shows that Vermont’s forest canopies interact with snow in complex ways. Precipitation, temperature, wind speed and elevation are key drivers of snow accumulation, but Ladue’s work shows that more complex forest canopies, measured using a metric he terms “entropy”, accumulate more snow than less structurally complex forests. Importantly, these more complex forests slow the rate of snowmelt.

“This is an important finding with implications for both forest management and water management,” says Wemple, who co-advises Ladue along with Bomblies. “Just as our forests in Vermont provide important ecosystems services by sequestering carbon, our structurally complex forests are providing an important service of slowing snowmelt, allowing replenishment of soil moisture and mitigating the risk of snowmelt-derived flooding.”

Research as a Public Good

The decades of monitoring and research are informing how we understand our fragile mountain settings and prepare for a changing future.

The state’s water quality monitoring program underscores the importance of long-term data. These headwater streams provide critical insights into the impact of shifting hydrologic conditions of high elevation streams.

“Long-term biological data reveals how extreme flooding events have negatively impacted the biological condition at both sites,” says Meaghen Hickey, an environmental analyst in the Vermont DEC Rivers Program. “Increasingly frequent extreme precipitation events statewide complicate watershed-level impacts, which is why long-term monitoring is essential for understanding and fulfilling DEC's mission of protecting the biological health of Vermont’s streams in a shifting climate.”

Vermont’s high peaks and complex topography create unpredictable weather. From sudden downpours to rapid snowmelt, this weather impacts the safety of communities, the resilience of infrastructure, and the strength of the state’s economy. The monitoring on Mount Mansfield allows researchers to understand this complicated meteorology and hydrology.

By leveraging the existing S2S stations on Mount Mansfield, Joshua Beneš, Associate Director of Research Facilities and Networks for the Water Resources Institute, is leading the effort to integrate this real-time data for public benefit through an initiative to establish a statewide mesonet. This initiative will provide timely data necessary for extreme weather response, agricultural planning, and a wide array of research initiatives.

“Our weather stations on Mount Mansfield are a key piece of our monitoring strategy,” says Beneš. “They will offer key insights to help forecasters improve lapse rate calculations, which is critical for understanding how prone the atmosphere in the region may be to extreme weather events.” The data provides crucial information on precipitation and snowmelt dynamics in high-elevation areas, which are most likely to contribute to flooding events.

Ultimately, the University of Vermont is working to ensure its investment in instrumentation and infrastructure. From Mount Mansfield to the Vermont Mesonet, UVM water researchers are empowering communities, protecting livelihoods, and providing unique learning opportunities that align with global monitoring initiatives and support the resilience of the state for generations to come.