It's true: there’s no shortage of problems in our world that need solving. And in our little corner of the world at the University of Vermont, there’s no shortage of talented minds that understand this truth: the time to start solving those problems is now. It's an "all-hands-on-deck" mindset shared by students and faculty that make it possible for hands-on learning opportunities to lead to new discoveries, innovations and research across every discipline. Here are just a few ways our students and faculty are working together to bring a brighter, greener, better future into focus.

![]()

Feeding Vulnerable Vermonters: Anitra Conover '21

Between her internship, data collection, surveys, interviews and questionnaires about food insecurity among Vermont’s refugees, junior global studies student Anitra Conover '21 hardly has a moment to consider that she’s never actually worked with the professor who’s been by her virtual side in this research for the better part of a year. For her, the work she and Professor Pablo Bose do to improve food security for resettled refugees in Chittenden County is all about making an impact, fast.

“These surveys and these interviews aren't just contributing to scholarship on food insecurity. They’re to benefit the participants of these surveys and interviews in a very immediate sense,” she says.

As a research assistant to Bose — a professor of global and regional studies and the 2021 George V. Kidder Outstanding Faculty Award winner — and as an intern with the Association of Africans Living in Vermont, Conover has been gathering information from hundreds of New Americans in the greater Burlington area about their access to nutritious, culturally appropriate foods and experiences with food assistance programs such as food banks, community pantries or delivery services.

When it comes to successfully serving these Vermonters, dietary restrictions, food preparation and cooking methods, for example, are all factors that could and should be considered alongside health and nutrition standards. Together, Conover and Bose are working to identify best practices and policies that might help bridge the gap between meals served to resettled refugees versus meals consumed.

“It's an issue that has been sharpened by the pandemic, but existed before and will exist afterwards,” Bose says. And for emergency food responders working through a global crisis, this research could help feed more community members when challenges arise and demand increases.

From her experience alongside Bose, Conover has come to realize that — just as her own, rich research experience can persist through a pandemic — the lifespan and impact of undergraduate reports and research can become so much more than simple grades on class papers. “What you do with a paper after a professor has graded it — based on its feasibility to enact the changes you want to see — has been something I learned with Professor Bose through this research that I wouldn’t have in class.”

![]()

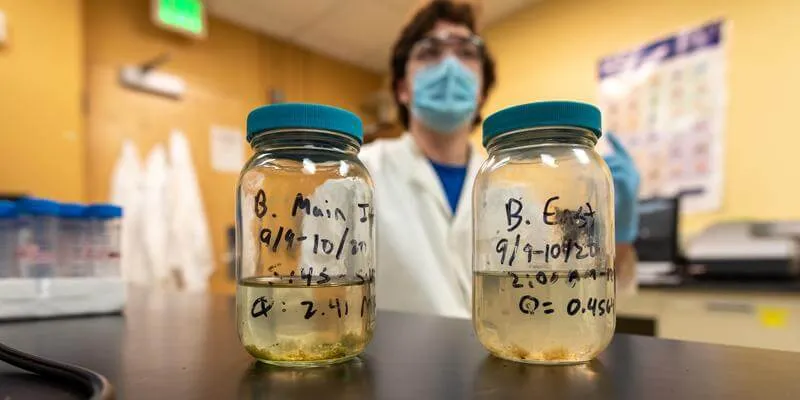

Turning Wastewater into a Warning Whistle: Ben Page '21

Ben Page ’21 holds two glass jars containing water samples. “This is from the east Burlington wastewater treatment plant and this one is from the main treatment plant,” he says. Floating in the water are “some solids,” says Page, and traveling with the solids may be a few bits of RNA from COVID-19. Under the bright lights of UVM’s Water Treatment and Environmental Nanotechnology Laboratory, Page will spin out samples from these jars in a nearby centrifuge to see if he can find any traces of the world-stopping virus.

When Page, a biomedical engineering student and Barrett Scholar, talks about his “love of transport phenomena,” he’s not daydreaming of race cars. Instead, he’s part of an ambitious research program, led by professor of civil and environmental engineering Raju Badireddy, to understand how flows of water, waste and life move through pipes, treatment plants and other parts of the built and natural environment. In this experiment, Page is helping Badireddy explore how wastewater might serve as an early-warning system for a spike in diseases. “Some viruses and other pathogens can take days or weeks to show symptoms,” Badireddy says, but antibodies and other traces of diseases may show up much sooner in the waste stream.

Using magnetic nanoparticles to bind virus fragments, Badireddy and his students are developing a system that they expect will be able to detect diseases in less than an hour after the water has been sampled — giving a rapid snapshot of how a community’s health may be changing.

In his first weeks as a freshman at UVM, Page emailed Professor Badireddy to see if there were opportunities to help in his lab. “He instantly invited me to stop by — and I ended up staying for three hours and missed two classes,” Page recalls. And he’s been working on research in the lab ever since, with projects ranging from advanced membranes to extract phosphorus pollution, to better approaches to making wastewater and seawater drinkable. In the fall, Page will begin a PhD program in chemical engineering at UMass Amherst. “I see myself using chemistry and an understanding of fluid mechanics,” Page says, “to help solve some of the problems facing society.”

![]()

Preserving Trees in the Chesapeake: Dayna Ullathorne '21

When Dayna Ullathorne ’21 arrived at UVM four years ago, she joined the Outing Club. She loved hiking up into the mountains, where she could see the forest rolling into the distance. She’d decided to major in environmental sciences at the Rubenstein School, so she asked another member of the club — a junior in the same program — what courses he’d enjoyed. “He told me: working with GIS and geospatial technology,” Ullathorne says. “So I did that. And loved it.”

Ullathorne has kept hiking and skiing in the Green Mountains, but this year she’s also been soaring — remotely — over the forests and waters of the Chesapeake Bay. After taking a demanding class on GIS and remote sensing with Jarlath O’Neil-Dunne, director of UVM’s Spatial Analysis Lab, Ullathorne was hired by the lab to help its scientists with a research project mapping the tree canopy across thousands of square miles surrounding the bay.

Now she’s part of a small army of undergraduate students in the lab — some as work-study, some as interns — who are turning aerial photographs and satellite images into land-use planning tools. The goal of the Chesapeake project: help landowners and decisionmakers understand how the forests in the bay area are changing. “Trees have so many benefits,” Ullathorne says — providing shade in cities, soaking up carbon in the fight against climate change and protecting the much-troubled Chesapeake Bay from pollution and headwaters erosion. “We’re figuring out where the trees are,” she says, “where new ones are growing, where they’ve been cut down.”

Her part of the research involves hours of looking at photos and LIDAR images — checking and correcting maps the ArcGIS software has automatically labeled. “Sometimes it will label shadows of trees as canopy, or there will be a building under the trees that needs to be identified,” she explains. Clicking between pictures, “It’s awesome to see how drastically a landscape can change in just four years — new agricultural areas, trees planted, a new pipeline.”

“Now when I go hiking," she says, "I wonder what the trail or woods looks like, from above.”

![]()

Empowering Data-driven Democracy: Clay Lerner '22

When it comes to making real, meaningful changes in our communities, there’s nothing more powerful than policy. And from Clay Lerner’s perspective, policy begins with people — informed people. But if there’s one thing his internship at an analytical consulting group and his research in POLS 230: Vermont Legislative Research Service (VLRS) have revealed, it’s that being informed is flat out hard.

For both his internship and VLRS class — a course designed in 1998 by Political Science Department Chair Anthony "Jack" Gierzynski to aid Vermont’s working General Assembly with non-partisan research and policy reports — Lerner ’22 is wading through public records, databases, legislation and voting records to help state lawmakers and national clients make informed, data-driven decisions and strategies.

And while those types of documents are legally accessible, “It's interesting how much information is publicly out there, yet it’s so difficult to get and to understand. I think it's made me more interested in trying to make information more accessible and easier to understand,” says the business administration student.

Outside the classroom, Lerner is chipping away at those barriers at his internship with The Burr Project, which aims to make politicians and government more transparent through a powerful database that centralizes information ranging from a politician’s voting record to their bill proposals. “There really is so much influential data out there,” he says. “While we can't prevent data from falling into the wrong hands, I think it's very important that we use it for good.”

Lerner is referring to the Cambridge Analytica scandal — which broke in 2018, revealing that personal data of Facebook users had been nefariously collected and used to influence elections years earlier — when he says “wrong hands.” But for all the data sleuthing that can go on behind computer screens, Lerner is researching and collecting public information the old-fashioned way.

“Honestly, it's a lot of reading through scholarly reports that somebody else has done, going into the footnotes or the work cited, and then seeing where that takes me. It's sort of going down a rabbit hole to find information from the first source.”

![]()

Farming of the Future: Shervin Razavi '21

When asked what he does with his time, Shervin Razavi '21 pauses, then says, “I spend a lot of time counting things, mostly organisms.” Which, as a double major in mathematics and biology, makes perfect sense. Earlier this year, he was working in a lab counting fruit flies. “I count larvae, mites, all kind of creatures,” he says, “and that takes a lot of time.” Instead of sliding into boredom, he began to dream of a technology that could do the counting for him. “It would probably just take a handful of code, and, theoretically, could do it faster and, eventually, be more accurate than me,” he says.

This is just one of several research efforts the Honors College student has underway, ranging from the purely imaginary to down-to-earth. One of them, close to the ground, is counting geese. Though he’s aiming to go to medical school, Razavi has been hard at work during the pandemic on a project to help farmers deal with the nuisance of Canada geese. With support from the student-led Catamount Innovation Fund, Razavi has been developing a system that would use infrared sensors to detect pests that might be chowing down on a farmer’s crop. “We’re starting by testing it on geese,” he says. An AI would be trained to read the thermal signature of the avian pests — and distinguish them from other critters on the farm. When the unwanted birds are remotely sensed, a computerized system could deploy drones that would swoop in, scare off the birds and leave the farmer, and their crops, undisturbed.

Working with UVM Plant and Soil researcher Arash Ghalehgolabbehbahani, a UVM engineering doctoral student and a local engineer, Razavi would like this Smart Farm project to aid regular farmers in the U.S. and beyond. “There’s a growing field of agritech called ‘precision agriculture,’ powered by satellites,” he says. “It’s very high-tech, but it’s often ridiculously expensive.” In the prototype experiments the team is testing at the UVM Horticulture Research Center, “we’re trying to develop a service that will be a reasonable price for mid-size farms,” he says.

Across his years at UVM, Razavi has signed on to help with a staggering array of research projects. “It’s made me realize how big of a gap there is between the biological research world and the computational research world,” he says, “and how much potential there is for integration.”

![]()

Discovery Continues: Learn more about the research UVM students pursue at the Virtual Student Research Conference, April 15.

Writing for this piece contributed by Josh Brown and Kaitie Catania. Photos by Josh Brown, Sally McCay, Kelly Schulze/Spacial Analysis Lab and courtesy of featured students.