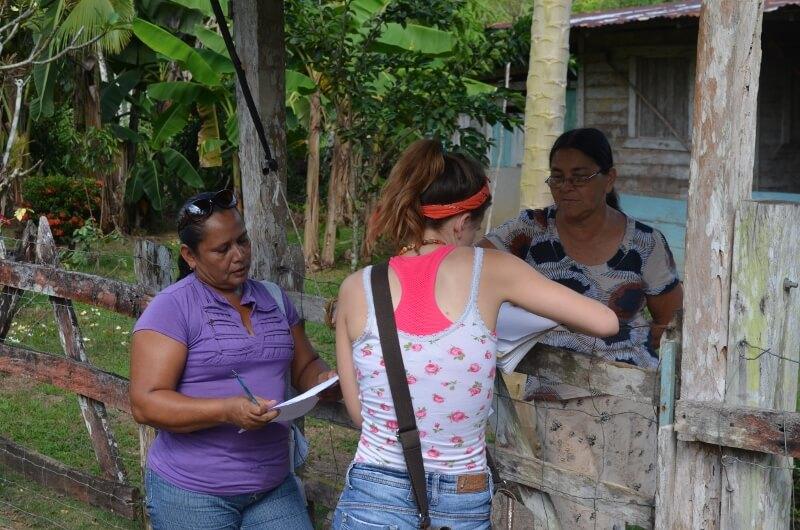

Temperatures drop to the single digits as the UVM campus in Burlington rests quietly during Spring Break in early March. But half a world away, a group of 18 UVM students is meeting with residents of the small village of Guadalupe on Costa Rica’s beautiful and stunningly biodiverse Osa Peninsula, trying to stay cool under the 95+ degree tropical sun. Equipped with a series of survey questions that they have built in collaboration with local community partners, small groups spread out across town to learn about residents’ priorities for the future here.

The UVM students are part of Communities, Conservation & Development, a service-learning travel study course in the Rubenstein School that has returned to this rural town every Spring for the past seven years. (Beginning in Spring ’18 it will be part of the semester abroad program in Costa Rica.) Under the leadership of David Kestenbaum and Walter Kuentzel, students work with locals to assess community resources and learn about various models and scales of economic development — and how communities balance development priorities with conserving Costa Rica’s famously rich natural environment. UVM students then contribute their data to a multi-year community profile project, which residents can use to advocate for themselves and their communities.

Guadalupe and Osa

Gaudalupe, and the Osa Peninsula more broadly, is an ideal place to study the nexus of conservation and development — and has been the most prominent debate in the region since it was settled. Lying in the far southeast corner and considered the “frontier” of Costa Rica, Osa remained largely unpopulated until the mid-20th century, when the government offered settlement incentives reminiscent of the U.S. Homestead Acts of the previous century. As such, it remains the least developed part of the country; a paved road connecting Osa to the rest of Costa Rica is just a decade old.

The peninsula is also home to Corcovado National Park, one of the most biodiverse places on the planet. Costa Rica as a whole—geographically no larger than New Hampshire & Vermont combined—contains some 5% of the world’s known plant and animal species; fully half of these can be found in Corcovado. It’s an ecological jewel, and yet it lacks much of the eco-tourism infrastructure that abounds in the rest of the country. This lack of development helps give tourists an “unspoiled” impression, but many investors also see it a huge economic opportunity. A massive marina, docks and infrastructure for cruise ships, and a collection of resort hotels are just some of the proposed projects currently being considered, with the promise of more jobs and opportunities in this rural area.

The village of Guadalupe sits at the intersection of dirt roads just outside the park’s borders; many of its older residents were some of Osa’s original settlers, and a number of the families in town were displaced — from either home, livelihood, or both — when Corcovado was formed, meaning they understand better than anyone the effects of competing environmental and development priorities.

So Kestenbaum, Keuntzel, and their students are trying to learn what the situation looks like not from the perspective of tourists or investors, but through the eyes of local people. At the same time, the course aims to provide residents with tools that will allow them to take advantage of a growing tourist industry on a community scale.

Service-learning, on several scales

The course is built around a service-learning framework, aimed at addressing the needs of the people living in Guadalupe and the Osa peninsula, as identified by the communities themselves. While this is true in service-learning courses generally, the Costa Rica experience is unique at UVM for its multi-layered service-learning approach. A persistent challenge of working with community partners is that they rarely operate on a neat semester timeline to match that of UVM students and courses, a challenge magnified during the short week on the ground in Guadalupe. So Kestenbaum & Kuentzel have set up short-, medium-, and long-term projects that contribute to community goals in spite of this mismatch.

The week begins with UVM students visiting the local elementary school at the teachers’ requests. Over the course of three mornings, working side-by-side with local environmental education organizations, they help the local kids put on a play about illegal poaching of wildlife, and a puppet show about turtle habitat conservation. Working with the elementary students is exciting for both groups in its own right, but also allows the UVM students to start building relationships that help facilitate meaningful conversation latter in the week.

In the afternoons, meanwhile, the UVM group conducts site visits at a number of eco-tourism initiatives, examples of community-based development that doesn’t rely on foreign investment and leaves a light ecological footprint: an organic fruit and chocolate farm; a butterfly nursery; a forest exploration at the Guaymi Indigenous Reserve; a mangrove boat tour operated by local fishermen trying to protect their stocks; a biological station; a family-owned zipline canopy adventure; a river gold mining demonstration.

These visits not only expose students to some of Costa Rica’s amenities and natural wonders, they also serve as the basis for medium-term service-learning projects. In recent years, UVM students have helped build websites and social media campaigns and write English language grants in support of primate conservation, among others.

Participatory Rural Appraisal & Community Development Profile

But the key to the program is the long-term data collection and family case studies that form the backbone of a community profile. The document is similar to what an international development consultant might put together on behalf of an outside investor, but in this case is created on behalf of local people.

“I loved that we were actively working with the community to achieve a common goal; I felt that our research compilation was contributing to the Guadalupe people’s overall vision,” says Lydia Gimm ’17, who participated in the Spring 2016 trip. “Because we worked with the locals to obtain a more concise view of what their community members wanted, we were able to compile a comprehensive report to help them achieve those objectives.”

With direction from Kuentzel, a rural sociologist, students use a community-based research approach called participatory rural appraisal — in which the community members themselves are in charge of collecting desired data — to assess existing community assets, the desired services it lacks, and the economic and environmental goals and priorities of the town. The time spent in the school, during daylong mini-homestays, and visiting various project sites also serves to build trust with the community.

Once back in Vermont, the students combine their data with what has been collected in prior trips, contributing to a community profile that gains breadth and depth with each passing year. Community liaisons back in Gaudalupe then translate the document, which community leaders can use to demonstrate their needs to the regional government, advocate for or against various development projects, and market to would-be tourists and other visitors.

The creation of the profile also helps build local capacity to continue the work once the UVM group returns home. The community liaisons who guide the class throughout the week are more aware and confident of their own expertise, and come away from the experience better equipped to be positive changemakers. “We’re learning to use the resources that are available to us,” says Pablo Largaespada, a wildlife guide who served as one of the course’s community partners. “Every project is a research project to meet anticipated needs and to focus on what most affects the community, and to create alliances. The new generations are the key to a balanced development.”

Expanded Horizons

Balancing economic growth, social benefit, and environmental protection — these are questions seemingly lifted from political discourse in our country, but are of just as much concern to people living in a rural town thousands of miles away. The opportunity to become so intimately familiar with the people of Guadalupe in such a short time is a testament to the relationships Kestenbaum has built over more than two decades working in Costa Rica, and is an incredible adventure and learning experience for the students. Approaching the future of Osa’s conservation and development through a service-learning lens allows UVM students to better understand these issues from the perspective of the people living there, and to put their skills and knowledge to work on the community’s behalf.