Americans once took up arms and fought a revolution to resist tyrannical rule. After America won its freedom, the Founders agreed that while the newly formed country would have a single president, Congress would provide substantial checks and balances to ensure accountability. But has the United States been able to maintain these intentions over the last two and a half centuries?

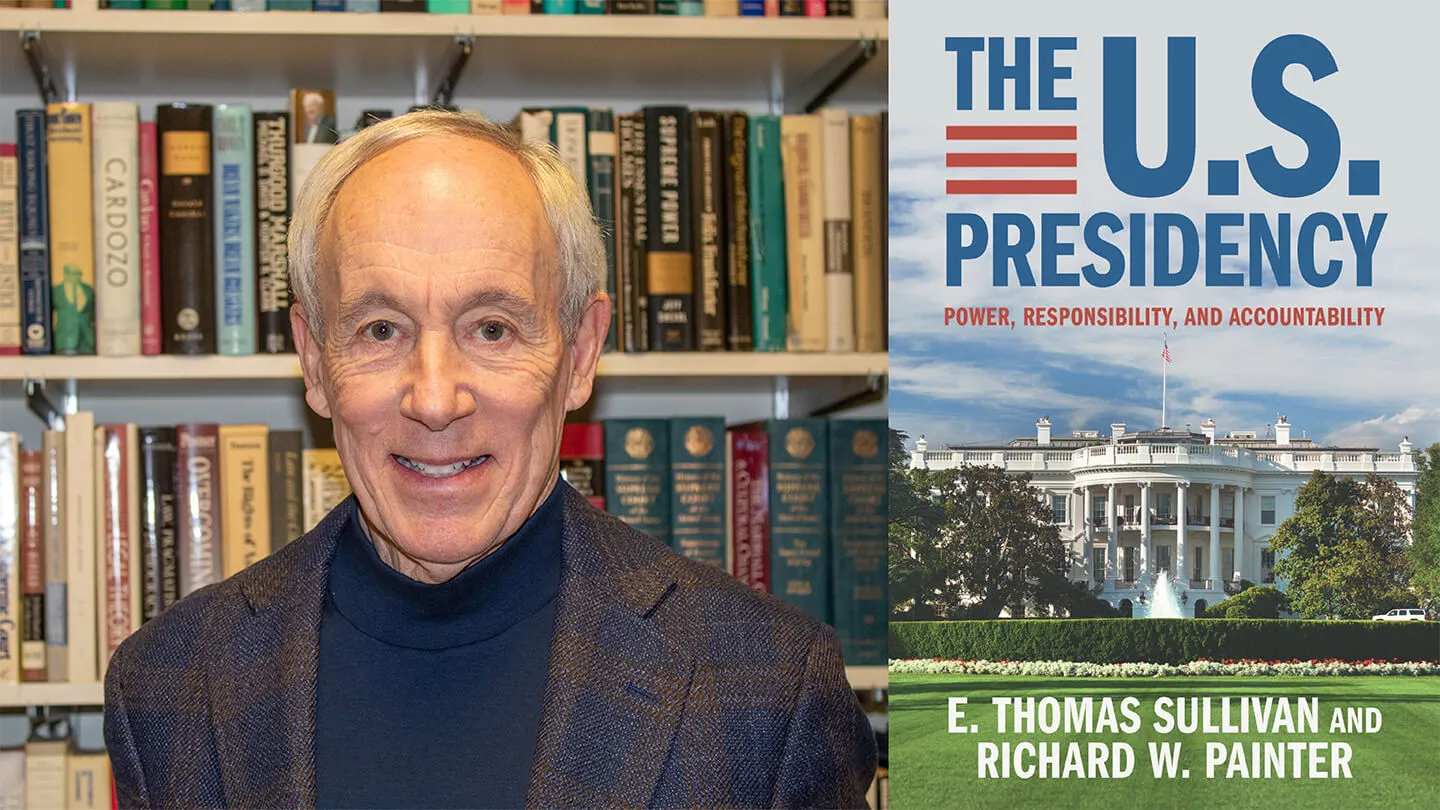

Thomas Sullivan, president emeritus and professor of law and political science at the University of Vermont (UVM), tackles that question and others related to it in The U.S. Presidency: Power, Responsibility, and Accountability. Co-authored with Richard W. Painter, professor of law at the University of Minnesota Law School, the book was just released in hardback by Cambridge University Press.

The authors offer a range of arguments for and against greater presidential power and look at how it’s acquired, how it’s used or misused, and how it’s held accountable to and by the people.

We asked Sullivan to discuss this timely issue with us.

College of Arts and Sciences: Why is the subject of presidential power so important right now? Why write a book about it?

Tom Sullivan: Our country is losing accountability in Washington, D.C. Ultimately, it’s about power, responsibility, and accountability of the presidency and the Congress. So, we set out to ask: What are their powers? What are their absolute legal responsibilities? And have we lost that democratic accountability that was the underpinning of all the Constitutional discussions?

This book has been in progress for two plus years, since before the last presidential election. We did not know at the time who the next president would be. We turned in the manuscript to Cambridge at the end of January, just a week or so after President Trump took office. So, obviously, we’ve had to add a substantial amount since the election and the inauguration.

CAS: In the Introduction, you note that, “ultimately the law today favors the view of a very powerful, and nearly unitary, executive.” How far is this from what the Founders wanted in a president?

TS: It is as far as you can imagine from what the Founders wanted. They were fearful from the first day of the Constitutional Convention in 1787 of having a dictator or a tyrannical leader because they were in the midst of fighting a war to repel and distance themselves from King George III in England—a living example of what they did not want. They debated it vigorously, and they were very clear that they wanted, in the words of Alexander Hamilton, “a strong, energetic leader as president.”

Hamilton carried the day with his “strong, energetic presidency.” But he and all the other principal Founders agreed that the Congress, under Article One, would predominate over the presidency, there would be clear accountability for decisions made, and there would be lots of checks and balances between the president and the Congress.

CAS: Are we currently seeing a strain placed on those checks and balances, or even a failure to maintain them, play out in real time?

TS: There’s a case to be made that we have very few effective checks and balances now. And this has happened largely because of the polarization and the politicalization that has occurred in our country and certainly in Washington, D.C.

I think the rhetorical commentary from both sides has been much enhanced and now we have, in some cases, a Supreme Court that has significantly changed its direction and significantly lessened the effectiveness of what the Founders deeply believed in and thought they were writing into the Constitution. And we see that in real time every day.

CAS: How has the advent of social media affected the rate of change and fluctuation in presidential power, and how has this affected the general public?

TS: I think we’re in a whole new era with instantaneous commentary rather than our more traditional State of the Union or presidential addresses from the Oval Office or other communications from a president. We have 24/7 news cycles, and in those news cycles you get lots of repetition and drama. And that has added to the attention, the focus, and, quite frankly, the power of a president to project policies and opinions about matters.

Previous presidents didn’t have social media available or rarely used it with the velocity and vigor that we see today. And we have the historical confluence of both the most politicized press we’ve probably ever had in our country and social media. This creates a very powerful network through which both positive and very negative things can flow quickly.

CAS: How is the shift toward a more powerful presidency affecting the average American?

TS: It’s catching the attention of all the electorate. This is happening particularly given the velocity and frequency with which we’re seeing our presidents use unilaterally executive orders to announce and implement policy changes.

I want to point out in fairness that this is not new. We’ve had many examples of unilateral action through executive orders by presidents. For example, Abraham Lincoln declared enslaved people free with an emancipation proclamation by a unilateral executive order. But the number of the executive orders and how quickly they are coming out now is new.

Whether you agree or disagree with the substance of these orders, the sheer number, the sheer quickness, the sheer sweep of the significant changes that are taking place is unparalleled in American history. It’s so much that nobody can take it in on any given day or any given week.

CAS: Was there anything that surprised you in your research? Anything you’d like your readers to know?

TS: I think people will be surprised after reading the history, with the Founders’ conversations and their vigorous debate, to see how far we’ve come from what they articulated. After all, the reason we had a revolutionary war was to ensure that we never again have a tyrannical, dictatorial, all-powerful leader. When you look at that arc of history and all its details and travails, it is remarkable and shocking how far away we’ve gotten away from the Founders’ intent.

We brought history out into the open in this book. Do we have sufficient accountability, checks and balances, as a nation? We leave that to the readers to determine for themselves.