What happens to wheat, oats, and barley production when winters are too warm?

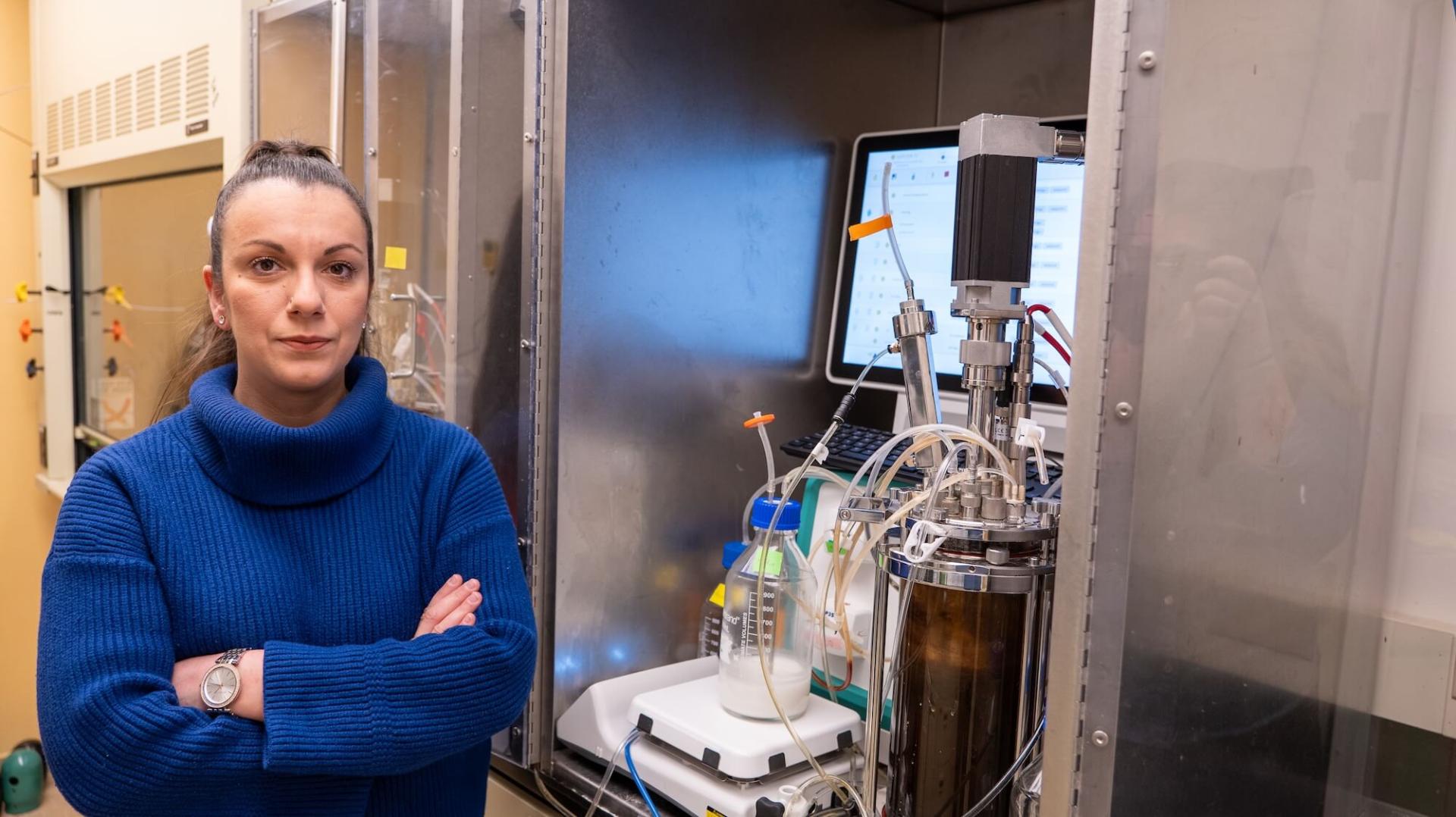

Hannah Shafer, a PhD Fellow at the Food Systems Research Institute and Plant Biology student, is working to find out. She studies the genetics of grasses to understand how rising winter temperatures might impact the development and productivity of these cereal crops.

Working in Dr. Jill Preston’s evolutionary developmental biology lab, Shafer researches how flowering grasses respond when their usual cold winter period is disrupted. These grasses have evolved to undergo a process called vernalization—they begin preparing to flower in the fall, require a period of winter cold, and germinate in the warming spring. As winters become milder due to climate change, Shafer is curious to learn how this interruption might change their flowering behavior and genetics.

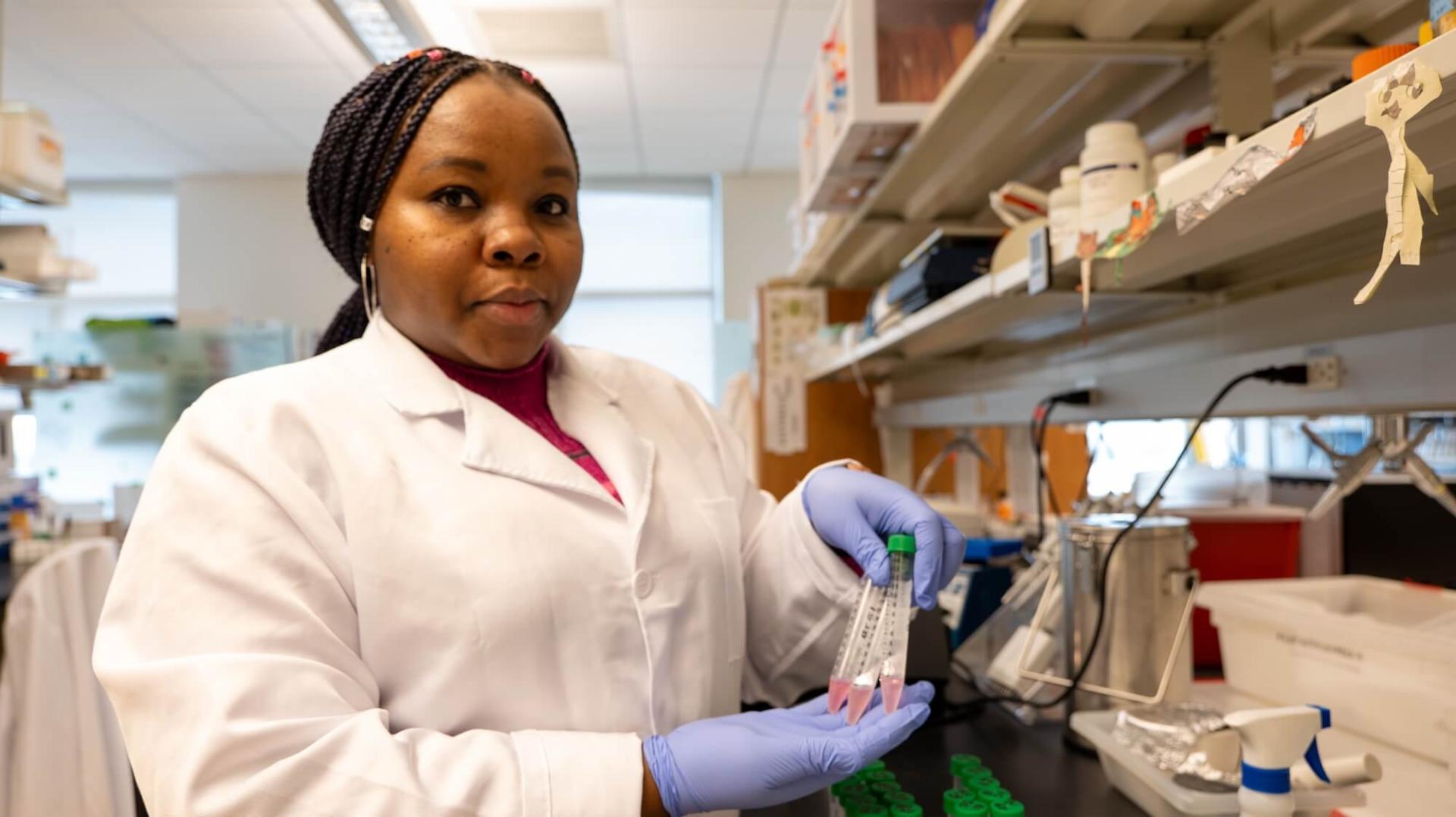

To do this, she is cultivating as many species as possible from the grass subfamily Pooideae in the University of Vermont greenhouse—so far, about 40 out of roughly 3,900 species. These grasses are relatives of the grain crops that make up a significant part of global diets and can inform how those plants could be sustainable in the future. “This work could eventually inform improvements in crops like wheat, barley, rye, oats, and forage grasses used for livestock and biofuels,” says Shafer. This research could eventually help crop breeders identify the genes that control flowering and development—key traits for boosting grain yields in a changing climate.

About the FSRI:

The Food Systems Research Institute (FSRI) at the University of Vermont (UVM) funds people and planet-centered collaborative research that connects disciplines and communities to answer complex food systems questions.