On a mid-September morning, as millions of acres of wildfires rage across the American West, author Alice Outwater ’82 discusses our nation’s current and historic relationship with nature through the acute focus of climate change. She describes the transformation she sees firsthand in the high mesa country where she lives in southwest Colorado—three-inch-wide cracks in the soil, 500-year-old trees dropping their limbs as they fight to survive a twenty-year drought.

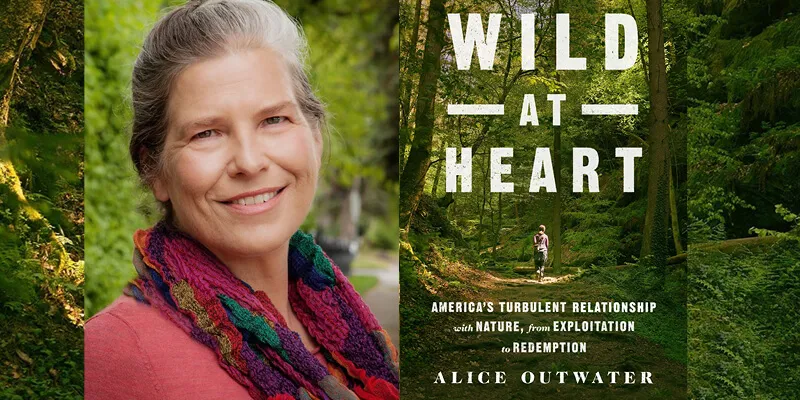

It’s not a happy picture. And Outwater, clear-eyed and straight-talking, educated as an engineer, is no Pollyanna. Yet, she says, “We don’t have to do environmental despair.” It’s an opinion informed by years of immersion in research and writing for her latest book, "Wild at Heart: America’s Turbulent Relationship with Nature, from Exploitation to Redemption," published in 2019 by St. Martin’s Press.

Outwater tells her story across twelve chapters, exploring aspects such as the relationship to the land of native peoples; impacts of industrialization and agriculture; nineteenth-century urbanization and the rise of parks preservation; and environmental activism of our times, among others. "Wild at Heart," listed as a Pulitzer Prize candidate, is engrossing to a casual reader while also seeming a likely choice for a text in a college environmental studies course.

The name Outwater might have a familiar ring to many in the UVM community. The writers’s father, the late John Outwater, was a longtime professor of mechanical engineering, and her mother, the late Alice Outwater, was a veteran counselor in the university’s Counseling and Testing Center.

The author earned her UVM bachelor’s in engineering, followed by a master’s from MIT. Her work on the clean-up of sludge in Boston Harbor led to her first publications, initially writing about the management of bio-solids for engineering journals, then publishing "Water: A Natural History," 1997, for a lay audience. She also wrote "The Cartoon Guide to the Environment," partnering with artist Larry Gonick.

While Outwater confesses that her recent research revealed that some aspects of our nation’s exploitation of the natural world were worse than she had realized, she also found hopeful trends, often realized in extremely quick pivots, motivated by changes in public attitude or legislation—the redemptive side of the American coin.

Case in point, Outwater shares the dynamics of a nineteenth-century craze in women’s fashion for birds. Quoting an 1872 British book of commerce: “a new and very pretty ornamental application of feathers is that of the entire head and plumage of some birds for fans and fire-screens; and the brilliant heads of many of the humming-bird family, mounted as necklets, ear-pendants, and brooches, form a novel species of jewelry.”

While that trend sparked a global feather market that put a great strain on some species (pity the era’s egret with its showy dorsal plumes), it eventually was key to the formation of the National Audubon Society, as Boston’s blue-blood women united, organized a national feather boycott, and rallied for protection of birds.

Reflecting on positive change in her native Vermont, Outwater observes the dramatic return of some species—bears, white-tailed deer, turkeys, loons—since her own childhood. Her research opened her eyes to the degree to which “connectivity,” creating travel corridors for wildlife, is taking place nationwide. More broadly in society, Outwater finds hope for the future of our relationship with nature in slowing population growth, Millennials eschewing car ownership, the wide interest in sustainable agriculture and restoring wildlife.

“I wrote this book because history shows that we should not despair,” Outwater says. “We have solved many environmental problems in the past. We saved the whales, healed the ozone hole, and cleaned up our air and water. We stopped killing everything. When you see how far we've come, it seems like dealing with global warming is just the next step.”