Picture a Vermont farmer. Now, be honest. Are you envisioning an older white man in muck boots with a herd of dairy cows meandering in the background? Perhaps a young man sporting Crocs and a man bun?

The University of Vermont’s five-year Who Farms? project wants Vermonters to expand that image. The effort, funded by a $90,000 National Endowment for the Humanities (NEH) grant and matched by local donors, seeks to broaden public perception of the Vermont farmer through comics, short videos, and a teaching guide designed for middle school audiences.

“The tourist stereotype is the seventh-generation white dairy farmer,” said Luis Vivanco, professor of anthropology and the former director of UVM’s Humanities Center, who spearheaded the project. “But others are entering the space of farming in creative ways, and we wanted to tap into those alternative visions and hear their stories.”

Consider Pius Sinzohagera, a Black refugee from Burundi who resettled in Vermont. He has farmed in the Green Mountain State for over a decade, growing habanero peppers, maize, tomatoes, and eggplants on his half-acre plot provided by AALV’s New Farms for New Americans program, which provides agricultural resources to immigrants and refugees in Vermont. But Sinzohagera still seeks acceptance as a farmer as well as a connection to local markets.

“If I don’t farm, I get sick,” he told interviewers in 2019. “What motivates me is work. Because when I am not working, I think a lot.”

The Who Farms? project brought together scholars from UVM’s Humanities Center and UVM Extension’s Center for Sustainable Agriculture along with community partners including Vermont Folklife, the Vermont Historical Society, and the Vermont Farm to School and Early Childhood Network.

Moving it forward involved a lot of trust building. The team formed a diverse advisory board to identify farmers throughout the state and to help build relationships between UVM researchers, community partners, and the farmers themselves.

“One major priority was that the storytellers control their stories,” Vivanco said. “We aimed for accountability and transparency at all stages about our goals and what are the moments where you can step in and correct the story.”

In addition to Sinzohagera, the project featured dairy farmers operating on the edge between collapse and survival, migrant workers who go to bed feeling lonely and alone, a grower of Abenaki ancestry reconnecting to his Indigenous roots through food, and a young couple committed to improving food security in Vermont.

Interviews occurred in the summer of 2019, just before the COVID-19 pandemic entered the everyday vernacular. Transcripts and videos were passed to artists from Eureka Comics, a Vermont-based company that specializes in educational cartoons, who spent a year developing the comic books with feedback from the farmers.

Using Comics to Convey Human Complexity

“When we were putting in the grant proposal with NEH we still felt like we had to justify that we wanted to do graphic format for this,” explained Cheryl Carmi G’19, co-organizer of the project and a doctoral student in UVM’s newly formed Transdisciplinary Leadership & Creativity for Sustainability program. “But there was this research showing that we use more of our brains when we are looking at text and image than either one of them alone.”

Josh and Meadow Squire operate a small family farm in Tinmouth, Vermont. Meadow grew up in a farming family but didn't know she wanted to continue working in agriculture until she lived abroad. It was then that she realized she could have the biggest impact on the world by improving food accessibility back home in Vermont.

Historically, comic books and graphic novels have not always been considered literature to be taken seriously. But they can be powerful vehicles for communicating ideas, increasing learning retention, and promoting representation. The proof, however, is in the data and the impact on the audiences they reach.

For instance, the Who Farms? project is not the first time UVM scholars used comic books to educate people about some of the messier and often unseen aspects of the state’s food system. In 2016, Julia Grand Doucet, a nurse at a Vermont clinic serving under-insured populations, approached Teresa Mares, a UVM associate professor of anthropology, about developing comic books for migrant workers struggling with mental illness and other health issues. The two partnered with the Vermont Folklife Center, Marek Bennett’s Comics Workshop, UVM Extension, and the Vermont Community Foundation to create Spanish language comics using oral histories of migrant workers in Vermont. The book, A Most Costly Journey, was the Vermont Reads 2022 selection and used in dozens of discussion groups across Vermont.

“That book has been read by way more people than my other book that was published by a good academic publisher,” Mares said. “And I love that.”

The initial purpose of A Most Costly Journey was to create a public health project for migrant farm workers, Mares explained. Using comics to disseminate information was decided in part because they are a familiar educational format in Mexico, she said, as well as a way to reach individuals with lower literacy levels. “Comics can convey a lot of information without a lot of words.”

Another upside: The comic format allows readers to connect with the story and see aspects of themselves in a cartoon character with a more ambiguous identity. This can be particularly important when one may be experiencing things that are difficult to discuss publicly like domestic violence or depression.

As copies of the comics circulated in migrant farm worker communities an unintended purpose also emerged: educating Vermonters about the experiences of some of the people helping to keep the state’s dairy industry afloat. Soon after, an English version was printed.

“That book has been read by way more people than my other book that was published by a good academic publisher,” Mares said. “And I love that. ... Anything that we can do to highlight the humanity and complexity of farm workers is important.”

Mares sat on the Who Farms? advisory board, helping shape the early stages of the project. Sha’an Mouliert, co-founder of the African American Alliance of the Northeast Kingdom and a racial literacy trainer, co-managed the project with Carmi for the last five years.

“Sha’an helped ground the work in the DEI (diversity, equity, and inclusion) principles and priorities that guide UVM,” Carmi said.

Listening Across Difference

Carmi was raised by labor organizers who owned a restaurant in Burlington. She understood from an early age that the front-of-the-house is sometimes different from the back-of-the-house and not something the public often sees.

“My one greatest hope is this project will help people find the heart and courage to listen across difference for stories,” she said. “This project is about farming on the land here, but anytime we listen to a story we receive so much more than is offered, and I hope this gives people space to listen and to care about one another.”

Carmi helped write the NEH proposal knowing that she wanted to counter the dominant narrative that Vermont’s farmers are overwhelmingly white and focused on dairy. She also knew that Mouliert’s work on the project would help to hold the team accountable to racial justice and equity.

“We developed standards of integrity,” Mouliert explained.

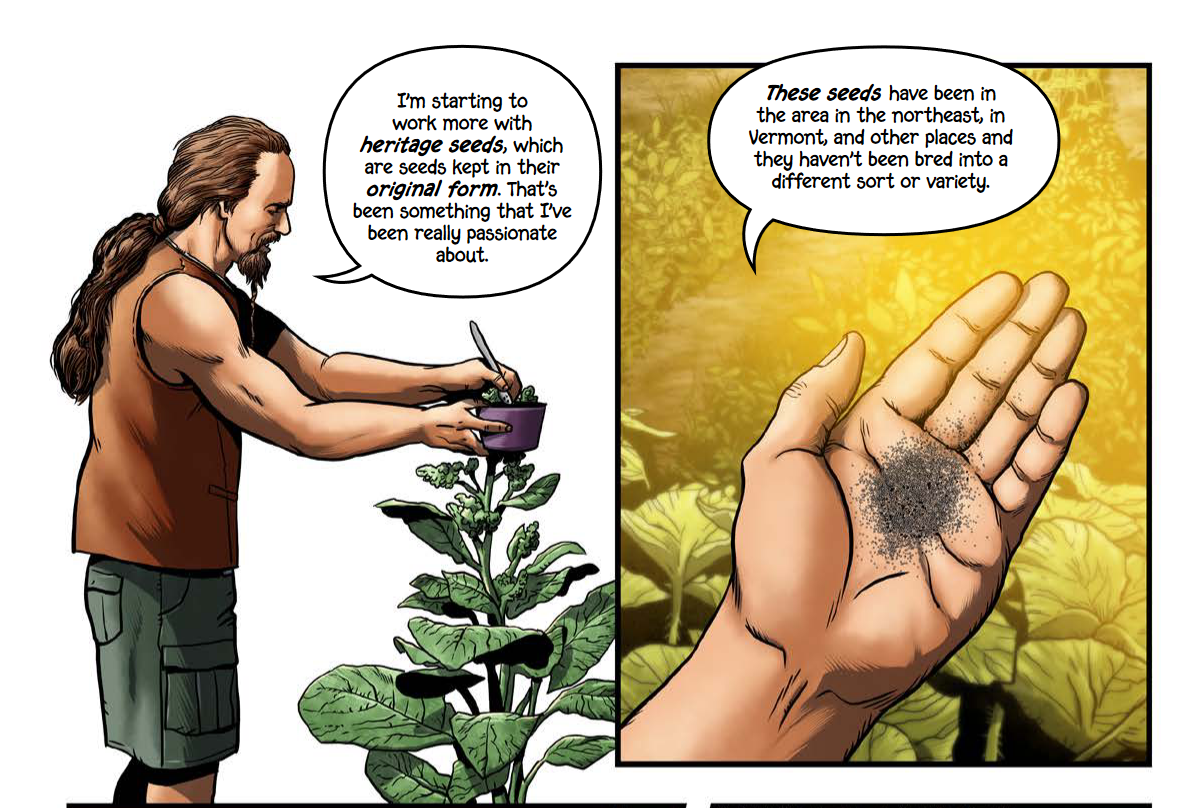

John Hunt is a Vermont farmer of Eureopean and Abenaki ancestry who grew up on a dairy farm. He watched farms go out of business and now works with heritage crops.

She helped the advisory council to both determine the final, diverse list of farmers whose stories would be included, and to develop a teaching guide. Mouliert and Carmi worked with the Center for an Agricultural Economy, educators through the Vermont Farm to School and Early Childhood Education Network, and teachers from the Burlington School District to align the material with state standards, which is now available on the Vermont Farm to School website.

“Our vision was that students would create their own interviews with farmers, Mouliert said, “That is a way that [the Who Farms? project] could continue.”

“It’s Time to Plant”

Although she spent the past five years on the project Mouliert is still processing the experience. She points to the day the team filmed their interview with Juan and Paco—two undocumented migrant workers from Mexico—who spoke candidly of the isolation and depression they feel while living apart from their loved ones. The conversation still haunts her.

“At the end of the interview we did a group hug and cried,” Mouliert said.

Touring the farm and hearing Juan and Paco’s experiences made her realize “oh, this is what living on a plantation is like,” Mouliert said. “Their story breaks those stereotypes that we had been and continue to be fed.”

She has begun handing the comics out to her neighbors, particularly those with different viewpoints, and found them to be well-received.

“The two stories that have stuck out are Pius and Johane and Juan and Paco,” Mouliert said. “It gave them something to think about.”

Pius Sinzohagera and Yohane Ntirundenga have farmed for more than a decade as part of the AALV’s New Farms for New Americans program. They still seek acceptance as "real" farmers.

And for Alisha Laramee, project manager for AALV’s New Farms for New Americans program, that was her hope when she asked Pius Sinzohagera and Yohane Ntirundenga, elders in the program, if they wanted to share their stories in the Who Farms? project.

“An opportunity like this helps them to be seen and heard,” she said.

Laramee sees the two men every day at the garden preparing their seeds and sitting under their shade umbrellas.

“It’s their home away from home,” she said. “They think of this land as theirs.”

One afternoon in late March, Laramee saw Ntirundenga, a fisherman in his past life, making fences out of yarn the way he used to tie fishing nets. The day the greenhouse opened, Sinzohagera was planting seeds.

“They are Vermonters, and they are Vermont farmers,” Laramee said. “I think a lot of people, if you don’t live in the Burlington area, are unaware that there is this whole generation of people who came into the state and who love agriculture. And there is this connection they have—you just know it and feel it.”

Language barriers exist between Laramee and many of the 100 refugee farmers at the site. But their connection to the land and to one another is clear when they are all in the garden. They are there with the same purpose.

“It’s time to plant,” Laramee said. “It’s time to get seeds in the ground.”

The Who Farms? teaching materials are housed on the Vermont Farm to School website. Public launch events are being planned for spring 2023. Graphics in this story appear courtesy of Eureka Comics.