In 1950, a young white couple by the names of Philip and Stephanie Barber purchased an old estate in Lenox, Massachusetts that was just down the road from Tanglewood, home of the famed summer classical music festival. They turned their new property into a destination called Music Inn, eventually converting the hay barn and carriage house into a performance and education space. In the words of John Gennari, professor of English at the University of Vermont (UVM) and author of the new book, The Jazz Barn: Music Inn, the Berkshires, and the Place of Jazz in American Life, the Barbers “fashioned their inn as a center for the study and performance of various kinds of folk music, blues, and jazz.”

This unlikely venue, a place deep in the heart of the Berkshires, drew legendary Black jazz performers—including John Lewis, Dizzy Gillespie, Max Roach, Oscar Peterson, Kenny Dorham, and others—many of whom also spent time as faculty-in-residence at what became known as the Lenox School of Jazz. Music Inn, as Gennari writes, “became pivotal to public understanding of the music’s African roots, its folk properties, and its place in American life and culture.”

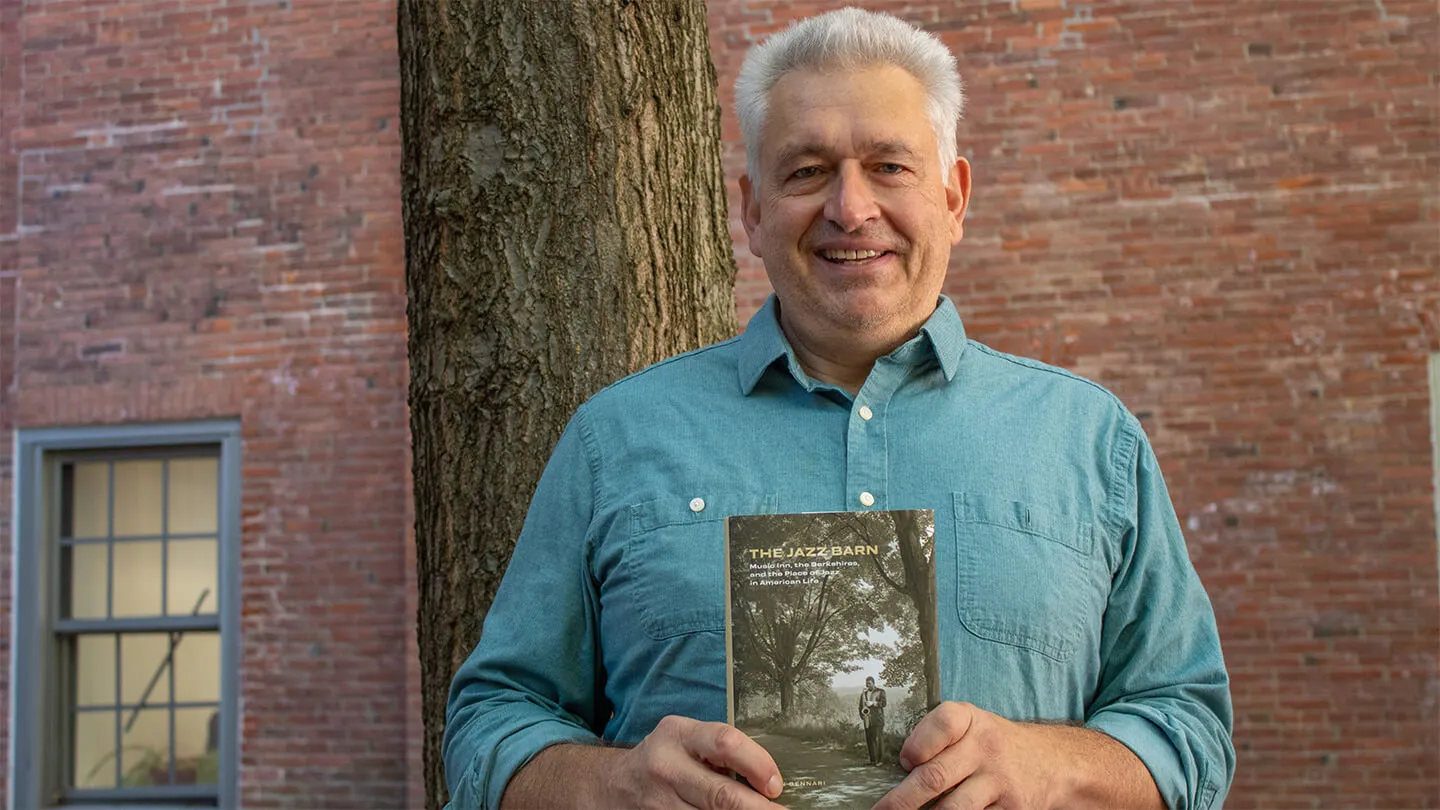

We sat down with Gennari to talk about how this surprising cultural hub became a cornerstone of jazz education and performance.

College of Arts and Sciences: What drew you to this topic?

John Gennari: I grew up in Lenox, MA, the town where Music Inn was located. When I was a teenager in the 70s, it hosted mostly rock, blues, and reggae concerts. I saw Bob Marley there. I saw The Band. I saw a very young, not-yet-famous Bruce Springsteen. It was a really special place.

It wasn't until years later, as I was working on my Ph.D. dissertation on jazz criticism and the role of the jazz critic in the broader cultural world, that I came across an arresting photograph at the Institute of Jazz Studies at Rutgers/Newark of John Lee Hooker, a young bluesman. He's sitting at a table, and behind him is a blackboard diagram charting the genealogy of American music, with the blues as a sort of spine going down the middle of it and “mainstream” written along the bottom. That really caught my attention because I was researching how the term had come to saturate jazz cultural discourse in the 1950s.

Jazz in that period was going off in different directions and critics and audiences were split on what constituted real jazz. This idea of a kind of through-line was the sort of thing that critics and writers about jazz were trying to articulate.

Years later, my wife and I were walking down the street in Stockbridge, the town just south of Lenox, and we saw this marquee for a place called Image Gallery—and there in the marquee was that photograph. I went into the gallery and met the photographer, an elderly gentleman named Clemens Kalisher, who eventually became a dear friend. He told me he’d taken the picture in 1951 at Music Inn. I ended up using the photograph in the book, Blowing Hot and Cool: Jazz and Its Critics, that came out of my dissertation

Kalischer shot hundreds of photographs at Music Inn in the ’50s, and I began to think that this important jazz story could be told not just in words, but in pictures.

CAS: You've mentioned a couple of times about jazz going mainstream. What did that mean and what sort of effect did it have?

JG: If you’re in the mainstream, you're essentially appealing to white, middle-class people. That was a powerful construct because jazz needed that kind of coding, because for so long it had been demeaned and demonized as a music of the lower classes. It was Black music, but also the music of lower-class whites who had a fluency with and interest in Black culture, such as musicians like Benny Goodman and Artie Shaw.

Because of American racial hierarchy, it was important in terms of livelihood and cultural esteem for jazz musicians to get the support of “mainstream” institutions so that they would be featured not just in Black newspapers and magazines, but in The New York Times and Time and Harper's, and that films and television specials would be made about their music.

Jazz is a deeply American music that subsequently became known as America's only original art form, America's indigenous music. But for most of its history, it was thought of as an embarrassment to elite tastemakers and others who were still deeply invested Victorian era concepts of culture. The things about jazz that we celebrate now—improvisation and freedom, both performatively and socially—were thought to be dangerous to the standards of music. It was thought to be transgressive.

CAS: Can you talk a little bit more about the physical space at the inn and how it shaped both the music and the experience for people listening to it?

JG: Yes, the main thesis of the book is that music is really place-centered, and the places where it's performed are deeply connected to its meaning. Now it may be the case that the Count Basie Band, for example, played the same tunes on Thursday night at Music Inn that it did the next night at Carnegie Hall in New York. But music is not just the sounds the musicians produce. Music is about listening, and music doesn't mean anything if people don't hear it. A term that that's important to a lot of us doing this kind of work is “musicking.” Music is a noun, an artifact. Musicking is an action, a physical manifestation of sound that gets heard. And what people bring to the experience is different if they're driving on backcountry roads, turning onto an unpaved lane through the woods, parking in a meadow, then walking up the hill to a hay barn that’s serving as the concert space. It’s this place where people are communing with nature in order to hear this music that was still considered to be urban.

There was also a lot of folk music happening there at the time, and that was important because many of the folk performers were blacklisted—this was the period of the Red Scare—and had trouble getting gigs anywhere else. So, all that contributed to Music Inn being a kind of refuge.

CAS: You talk in the book about how Music Inn “sorted through [the] complexities” of racism and the racial order of its time.” Can you speak a little bit more about that and how that showed up in the music?

JG: If Black musicians, writers, and artists had not lodged at Music Inn, they very likely would have had difficulty getting hotel rooms in Lenox or Stockbridge. This was the United States of America in the Jim Crow era, and even a place with a deep history of abolitionism and progressivism was not immune to that. The artistic director of the jazz school at Music Inn was John Lewis of the Modern Jazz Quartet, one of the great African American pianist/ composers. And there's a lot of testimony from the white musicians who arrived harboring racist ideas about Black people and Black culture—even though they were deeply into jazz—and then just had their minds blown by discovering something quite different.

And so, during the Civil Rights era you had white people simply being asked to tolerate black people, but here, at Music Inn, white people were coming for the purpose of encountering Black excellence and Black leadership. That is a complete scrambling of the American cultural algorithm during that period. The class differences are important, too. The Modern Jazz Quartet, Miles Davis, and other Black musicians became synonymous with elegance; a well-tailored suit became part of being cool.

A lot of the white interest in jazz came from a desire to rebel against bourgeois parents and upbringing. But for the Black community, it was a celebration of African American social mobility into bourgeois dignity and respectability. So those kinds of tensions and frictions are really interesting, and it’s what was being played out at Music Inn.

CAS: You talk about Music Inn’s Jazz Roundtables in the book. Can you speak a little about their importance?

JG: It all started with Marshall Stearns, an English professor who caught the jazz bug as a young person and began collecting jazz records. He was one of the founders of a jazz appreciation organization called the United Hot Clubs of America, and he wrote for jazz magazines and became a well-known jazz intellectual. Stearns argued for cultural continuity between Africa, the Afro-Caribbean, the American South, and jazz, and he brought them together at a series of summer seminars, called Roundtables, featuring musicians, scholars, artists, and writers. There were African drummers and dancers, Caribbeans, Trinidadians, Jamaicans, Calypsonians, folklorists, poets, the list goes on. The Roundtables received a lot of attention in the national press, as it was a new idea to consider jazz as something to be studied. It’s an important part of the whole story.

CAS: How did things change in the 60s and 70s?

JG: During that time in America, there were enormous changes, and Lenox was no exception. 1961 marked the end of the Barbers’ ownership of Music Inn, and under new ownership it moved in the direction of folk music. It became the place where people came to hear singers like Bob Dylan, Joan Baez, Joni Mitchell, and a young Carly Simon with her sisters. Then in the 70s, as I mentioned earlier, it moved in the direction of rock, blues, and reggae.

A lot of the Black and white musicians who went through Music Inn as students or faculty members became really important to the establishment of jazz studies programs at universities, colleges, and conservatories. Some of them became connected with the Black arts movement in places like Chicago, New York, and St. Louis, and by the mid to late 60s and into the 70s, jazz was very much at the center of that movement.

There wasn't an effort early on at Music Inn to separate out jazz as this kind of exalted, high art music. But by the end of the 50s, you began to see things like the third stream movement, which is the idea of fusing jazz and classical music. It was kind of a short-lived development within the history of jazz, but since then, the idea of multiple streams connecting with jazz has been central. Jazz musicians were listening to all kinds of music and incorporated it into their own art. They listened to East Indian music and South American music as well as rock and roll and Black popular idioms like R+B, soul, and gospel.

But all of this was at odds with the jazz-as-high-art scripture that was being proselytized at Music Inn. So, what was happening there was simultaneously progressive and limited in a way that became clear as the’ 60s and ‘70s rolled out and the music just kind of exploded in all kinds of different directions. Music Inn was crucial in helping usher in jazz’s latest avant-garde—Ornette Coleman and Don Cherry were students at the Lenox School of Jazz in the summer of 1959—and it provided much of the intellectual foundation for the concept of a coherent jazz tradition. But, it didn’t catch the wave of Black urban popular music (Motown, Stax, etc.) that was so crucial to 1960s American culture.