At Special Collections, don't expect self-service. Patrons won't be beelining for the stacks, grabbing what they need and checking out. Instead, expect a stop at the front desk where a librarian will ask what brings you to the bottom floor of Bailey/Howe Library. After all, the contents of the collection are something worth protecting -- rare books dating all the way back to 1106; first-edition, signed copies; intricate tomes hand-made by artists. But there's another reason, beyond security, that a librarian is poised by the door.

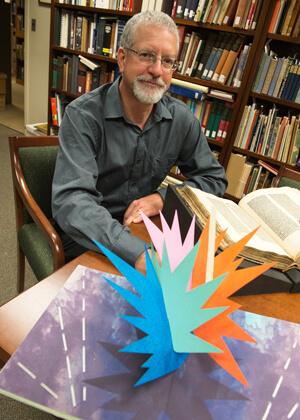

"We like to think it's not just because things need to be kept in closed stacks," says Jeffrey Marshall, director of Special Collections, "but because the context we can provide as specialists makes the collection more useful to people. Really, the whole focus of our efforts, which includes everything from cataloging to doing conservation work on books and papers, is focused on how we can help people use this stuff."

This year, UVM's Special Collections is celebrating 50 years of sharing the signature books, papers and artifacts that make up the collection. In 1962, when John Buechler was hired as the first head of the department, the collection was created from the rare books and other Vermont materials from Billings Library and the James B. Wilbur collection of Vermont research materials from the Fleming Museum. Five decades later, Special Collections’ holdings now include 80,000 books and pamphlets, approximately 200,000 photographs and other images, upwards of 7,500 maps and more than 8,000 linear feet of Vermont manuscripts. You'll find George Washington's signed copy of The Contrast, the play by Royall Tyler that's considered the first comedy written in America; hundreds of Vermont soldiers' letters and diaries from the Civil War; digital images of 1910-1960 Burlington taken by photographer Louis L. McAllister; one of the best collections of artists' books in the country; and a new gift to the collection this month: a sombrero owned by celebrated American poet Hart Crane.

To celebrate the occasion, Mark Dimunation, chief of the Rare Books and Special Collections Division at the Library of Congress, will speak on "The Value of Special Collections in the 21st Century," on Friday, Sept. 21, at 5:30 p.m., in North Lounge, Billings. The event, to be followed by a reception and champagne toast, is free and open to all.

Billings is an apt location for the celebration. Not only is it the original home for a portion of the collection, it's the planned future home of the department. Fundraising is under way to renovate Billings to prepare it as a site for Special Collections as well as the Center for Holocaust Studies and the Center for Research on Vermont. It's a move, Marshall says, that will give the collection, which is approaching 20,000 linear feet of shelf space, "much needed breathing room" -- as well as state-of-the art climate control to help preserve the items for decades to come.

"It's an extremely important gesture on the part of any kind of academic institution," Dimunation says, "that they create the right kind of home for this research. It shows that there's an investment in the future of working with real materials that's extremely important to the academic program. As libraries, more and more, become purveyors of information, it's fundamentally important that they carry forward, as well, the experience of working with the actual, physical object."

That's the heart of the talk he has planned for Friday. "I'm really talking about the value of the physical object and why we need the real thing," he says. "Materials from the past have a certain resonance, and that resonance cannot be conveyed digitally and doesn't transfer through a photograph. It only works when it's in the hands of a reader in a setting in which people can explain and talk about the meaning and value of that object."

Dimunation knows a thing or two about the importance of "the real thing." For more than a decade, he's overseen the task of restoring Thomas Jefferson's library, two-thirds of which perished in a fire at the Capitol on Christmas Eve, 1851. With the work nearly complete and now on permanent exhibit at the Library of Congress, the collection showcases the 4,000-plus books Dimunation has tracked down, exact matches of the books Jefferson owned, and displays them in the manner Jefferson intended: in a circle, organized by the tenants of the Enlightenment -- memory, reason and imagination. There's value, he says, in "having in our possession the library that shaped the mind of the author of the Declaration of Independence….in having that corpus of material readily available." He'll talk about Jefferson, as well as "a little Susan B. Anthony, a little Houdini, Lincoln, a whole host of people," he says, during his lecture.

For all the value of the physical object, there's value, too, say Marshall and Dimunation, in digitizing collections so they're accessible online. Unlike in other areas of the library, where "digital technology can be seen as the vehicle through which we can reduce the number of physical artifacts we retain in a collection," Dimunation says, "in Special Collections, it should be handled in tandem."

At UVM, the Center for Digital Initiatives does just that, scanning and archiving a selection of the manuscripts, books and images unique to UVM's collection. McAllister's photographs, slide images of the Long Trail, the Civil War letters, Vermont Congressional papers, maple recipes and other collections are available for browsing on the CDI website.

"We see the Web as an access tool, not a preservation tool," Marshall says. Access to and use of the collection is important to Marshall. That's why since becoming director in 2006 (following long-time director Connell Gallagher), he's paid special attention to increasing the number of classes visiting Special Collections and integrating its holdings with coursework. The number of class visits reaches 60 to 70 per year and include everything from botany courses looking at the collection of herbals to see how plant descriptions and depictions have changed over the centuries to printmaking courses investigating printing processes and how printers and artists have historically made illustration and text work together.

"Teaching is the most important thing we do," Marshall says. "If we're not teachers, then we're just guardians, and that's not what we want to be."

Special Collections Celebrates 50 Years of Service

ShareSeptember 19, 2012