What impact does maple sugaring have on the broader forest ecosystem? It’s a question that often goes unasked, yet biodiversity in maple forests is essential for the long-term health and productivity of Vermont’s forested landscape.

This summer, a team of undergraduate and graduate students led by Tim Rademacher, Director of Scientific Research at the Proctor Maple Research Center (PMRC), set out to explore that very question.

The students researched biodiversity in the sugarbush to determine whether there’s a correlation between tapped forests, where sap is harvested using modern production methods, and untapped forests. Their findings could shed light on how tapping affects forest ecosystems, or maybe even whether biodiversity itself influences sap yield.

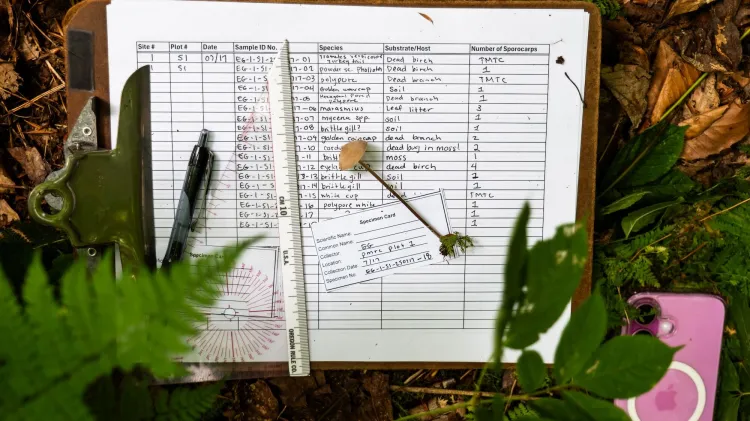

Each student studied a different component of the forest from fungi to mosses to tree-related microhabitats in a series of randomly generated plots of land at PMRC and neighboring lands, in addition to the Smokey House Center in Danby, Vermont. Multiple times a week, they trekked together into the forest to collect samples and record data. Among the students were Walt Regan-Loomis and Emma Griffith, Food Systems Research Institute Undergraduate Research Fellows.

Vermont produces 53% of the nation’s maple syrup from its forests. “We’re in such a great position where sugar makers own a lot of land in Vermont,” says Walt. “We have an opportunity to make biodiversity a profitable goal which is exciting.” Walt says that there are already some guidelines for biodiversity in forest management practices in the maple industry but those focus heavily on the trees themselves rather than the “mosaic of what is biodiversity in an ecosystem.”

Walt is a rising junior at UVM studying plant biology. This summer, they focused on the biodiversity of moss and other bryophytes - plants which absorb water and nutrients from the air. They were excited about the project because the Mount Mansfield areas around PMRC has one of the highest pockets of bryophyte biodiversity in Vermont.

The other fellow, Emma Griffith is a Biology major with minors in Spanish and Plant Biology. She studied macrofungal biodiversity in the sugarbush and is interested in the unique nature of fungi. “They’re funky,” she said. “They have like funky sexual cycles, lots of different life stages and forms that can look different and look weird.”

Walt and Emma’s projects were part of a larger team effort collaborating to collect and analyze the data. “Working on a team has been so much fun. Everyone's just a nerd about something,” said Walt. “Someone will see a cool animal or a mushroom, and everyone's stopping to check it out, which makes it really fun and encouraging to be surrounded by people who also have that appreciation for it.”

Each summer the Food Systems Research Institute funds students like Walt and Emma to work alongside UVM researchers tackling critical food systems topics. These fellowships aim to develop the next generation of food systems researchers. “This is the first big research project that I've been able to be a part of from start to finish,” said Emma. “I'm learning how to set up methods, how to conduct my methods, how to get everything together from start to finish. So, it's a big learning experience. Honestly, this has been my favorite summer at UVM so far.”

About the Food Systems Research Institute:

The Food Systems Research Institute (FSRI) at the University of Vermont (UVM) funds collaborative research that puts people and the planet first, unites disciplines and communities, and answers complex questions about food systems.

The FSRI gives researchers the freedom, resources, and time to engage community stakeholders, including decision-makers, farmers, and food systems actors, about issues and opportunities across our food system. This results in relevant, widely disseminated research that informs policies, practices, and programs locally and regionally for a more resilient and accessible food future for all.