UVM’s Center for Community News (CCN) is helping breathe new life into local news outlets across the country. Inspired by the success of UVM’s Community News Service (CNS), which matches students with local news outlets in Vermont to provide reporting, CCN already supports around 170 partnerships between universities and local news organizations across the United States—and it’s only in its second year of existence.

“Since the early 2000s, the number of local news outlets in America has dropped significantly,” says Hannah Kirkpatrick, research director for CCN. “We’re losing an average of 2.5 outlets a week now, and that is not good.” This trend of shutdowns means there are places that are at risk of becoming news deserts, counties with no, or only one, local newspaper.

“The shift toward national news has accelerated political polarization in the country,” Kirkpatrick explains, “and we think that is a great risk to democracy.” Research has shown that without a local newspaper or public radio station or even an online outlet, people are less connected and less engaged in local democracy, which leads to less voter participation and a smaller pool of candidates running for local office.

CCN recently expanded its own research and released results from an ongoing survey, The Impact of Student Reporting, about public-radio collaborations with universities. “Currently, only about three-quarters of the university-licensed public-radio stations we surveyed had some level of student involvement,” Kirkpatrick says, “and most of that involvement is limited to traditional internships rather than students coming on in a collaborative sense or taking a class, etc.” In their research, CCN found the vast majority of university-licensed public radio stations want to collaborate more with their university and its students.

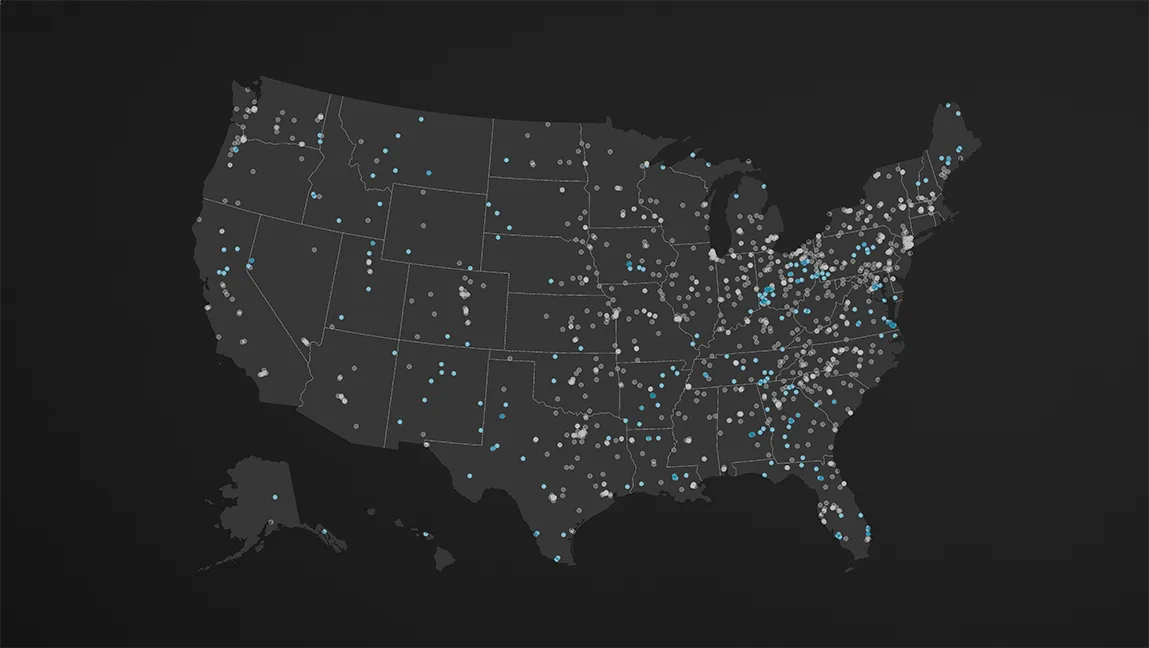

By helping to support as many existing local outlets as possible and giving colleges and students the power to step in and help, CCN aims to meet that desire for more collaboration and, importantly, stem the flow of closings. “We’re looking at where these places are and identifying those that we could provide some support to,” Kirkpatrick says.

Richard Watts, senior lecturer in the College of Arts and Sciences, founded CNS in 2019 through his position as an internship coordinator. He was inspired to create CCN when he saw the potential for a national initiative that would follow the CNS model. So, during a sabbatical in 2022, he traveled around the country and talked to people about the program, garnering a lot of interest along the way.

The mission of CCN is to “inspire and enable collaborations between local media outlets and students.” They work toward this goal by continuing to innovate the model created by CNS, focusing mainly on building and maintaining a database of academic and community news programs that are working to revive and support local news throughout the country. Any colleges and news outlets that want to launch their own partnership or expand their efforts are offered direct support from CCN, which also provides training (via a seven-week Zoom course) to citizen reporters who can offer supplemental coverage for local newsrooms.

The list of nearly 200 partnerships identified by CCN continues to grow. “They are all at different stages in their programs,” Kirkpatrick says. “Some of the schools may not have even produced a student story yet, but they are in the process of getting something started.” This could be setting up a class, talking to local outlets, or setting up statehouse reporting (stories about state-government affairs) programs.

According to Kirkpatrick, students who report for CCN face some of the same challenges that adult professional reporters do. “Some communities are more resistant to the media than others,” she says, “and high turnover rates of student journalists offer a challenge in building trust with the community. But in the programs that have been around for a little longer, it’s less about the reporters than it is about the university that is standing behind them.” She notes that it’s not an insurmountable challenge. “Trust can be built up over time.”

Kirkpatrick says that CCN was initially focusing more on programs close to home, “and then Richard made many connections by traveling around. During his sabbatical he spent a lot of time traveling to the Southeast, so we identified a lot of programs there.” One such program is thriving at the University of Georgia. The Oglethorpe Echo, a local paper that was going under, was taken over by the university, and for the last couple of years students have been successfully running it.

Other examples abound. At Queens University in North Carolina, much of their work now gets published in Qcity Metro, an online outlet. The University of New England, which is a new partnership, is working with a number of outlets to provide student reporting for free in exchange for credit. And Southern Adventist University in Tennessee offers a local section in their student newspaper.

“A lot of the student statehouse reporting bureaus have their own website where they publish their work, so they’re basically creating their own local outlet,” Kirkpatrick says. There are also quite a few programs that offer specific types of reporting, such as environmental reporting. One example of this is a collaboration with an already existing outlet called Planet Detroit at the University of Michigan.

Then there’s Amplify Utah. “This is an incredible example of an existing program that has been growing and expanding quite a bit,” Kirkpatrick says. Founded at Salt Lake Community College, its students contribute to The Salt Lake Tribune and the Standard-Examiner in Ogden, among other outlets. The nonprofit has now expanded to partner with the University of Utah and Utah State University. Students submit their stories that are then placed in a repository, where outlets can pick up pieces to publish as needed. Students also lend their voices to stories aired on a Utah radio station. “Amplify Utah actually put together a playbook of how they started their program,” Kirkpatrick says, “which is going to be really helpful for other programs in the future.”

In each CCN program, students are getting crucial experience that the job market demands. Their work is vetted by faculty members and edited either by a faculty member teaching a class or by a professional editor. “I think the common thread among all the CCN programs is that the students are getting involved and the work that’s coming out of them is high quality,” Kirkpatrick says. “It’s really a win all around for everyone.”