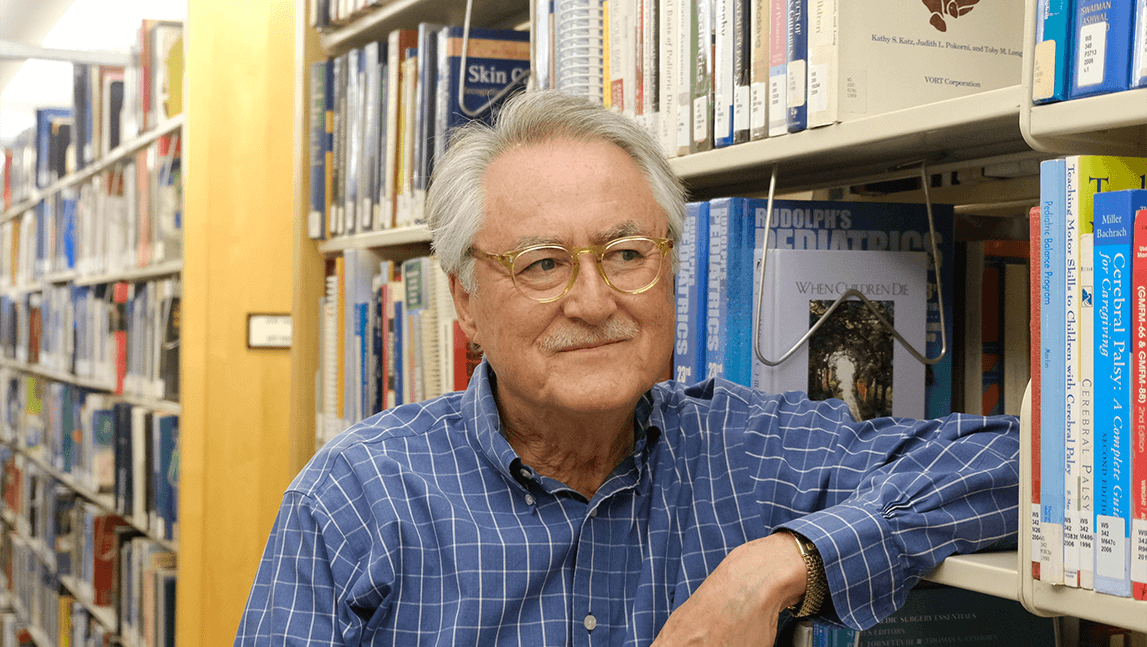

People give Allan Kellehear’s students a quizzical look when they hear about his new course about death and dying. But there’s one thing he’d like to get straight.

“We’re not studying death or dying,” said Kellehear, who joined UVM as a professor this fall. “We’re studying living people.”

A medical sociologist who’s an expert in end-of-life and palliative care, Kellehear has worked and taught around the world, from his native Australia to the UK and Japan. And he’s bringing more to Vermont than just a thought-provoking class. He’s known for developing local programs for palliative care, a model he refers to as “compassionate communities,” and wants to work on some here.

“This is about getting schools and workplaces, neighborhoods, faith groups, to take up their responsibility to participate in end-of-life care for their citizens,” he said.

He’ll be doing a bit of that in Vermont, he said, explaining that he’s been working with colleagues at the Larner College of Medicine to develop programs.

Attend one of his lectures, and you’ll be compelled to come back next class to hear Kellehear keep going. Kellehear paces around in front of his class with a mischievous energy, seemingly relishing in the mystique that comes with teaching about what he calls one of the “great taboos” and bringing up another whenever he can.

“When you’re studying one of the great taboos — sex, death, madness — people look sideways,” he said. “It’s an attraction and a repulsion. That’s what taboos do, it’s anthropology 101. But what I’m hoping students get from studying one of the great human taboos is a greater thoughtfulness about how the rest of society works.”

You get the best insights, he said, when you look into a room you’re not supposed to be snooping in.

He likes to tell a story from his days as a student, when he was taken by his psychology professor to observe monkeys at the zoo. The assignment was to record their behavior every 30 seconds.

“It occurred to me that if we were to do the same exercise in sociology, we would not ask for that type of information,” Kellehear said. “We would ask: What did the cage look like?”

The point to him was why the monkeys behaved how they did — were they impacted by how visitors acted? Did the behavior of other animals in nearby cages change how the monkeys acted?

“The idea of studying behavior without studying the social and physical context seemed rather meaningless,” Kellehear said, “because the clue to the meaning of behavior is not the behavior itself, but the setting.”

Given his field of study, Kellehear has had a lot to chew on over the past year and a half of the Covid-19 pandemic. His thoughts, unsurprisingly, go against the grain.

“Most people think about the infections, and they think about sick people, and they think about the people who have died of Covid,” he said. “But if you're looking at the cage, then what you see is the rise of medical power. What you see is the rise of the public health storyline and how powerful that has become. And the problem with an increasingly powerful medical and public health voice is that community voice gets eclipsed.”

Communities should be able to balance concerns about spreading the virus with support for folks who are dying, the professor said, pointing to how at times during the pandemic people have been barred from being with their loved ones at the end.

“Yes, it's important that we lower the infection rate,” he said. “Yes, it's important that we don't get a greater rate of unnecessary deaths. But that said, we have to accept that there will be deaths, there will be dying and there is just as an important need for people to be with their dying loved ones, to attend the funerals, to be able to give people the support, the hugs that they need, when they lose their loved ones.”

Along with teaching a course and building a community program around palliative care, Kellehear plans to continue his research at UVM. The question he wants to tackle: At what point do people start thinking about themselves as dying people?

“There's been very little work done on that intersection between an old person's identity and aging identity and the identity of someone who will die very soon,” he said. “I'll be exploring that.”

Jared Pap is a Sociology Junior with a passion for writing stories.