We owe our current high standards of medical care to the people who participate in clinical trials research. These carefully designed studies help answer specific questions about the safety, effectiveness, and long-term impacts of new medical approaches—therapeutics, vaccines, and medical devices—in human volunteers. By participating, volunteers play a crucial role in advancing medical care and protecting the health of others. While participation is always voluntary, some trials, especially those that require healthy volunteers, compensate participants for their time and effort.

Meet some of the people in Vermont who volunteer for clinical trials and get a glimpse into the research process at the Larner College of Medicine.

UVM graduate Trevor Hultgren ’25 jokes around with Physician Assistant Martha Kirk as she checks his pulse, examines his skin, and listens to his heart through a stethoscope. Hultgren’s physical exam in the Clinical Research Center at the University of Vermont Medical Center is a follow-up visit for volunteers in a study investigating an experimental treatment for dengue fever, a mosquito-borne viral disease that poses a growing risk in tropical regions worldwide.

“It’s interesting, kind of fun, and it helps people,” Hultgren said when asked why he volunteered. “Both of my parents have participated in clinical trials, and so I wanted to.”

During her checkup, Olivia Tarney, age 27, remarks on the importance of demystifying clinical trials participation. “It’s not scary, it’s just like a series of doctor’s appointments,” said Tarney, a recent UVM public health graduate and research assistant. “I feel that science and public health are so important, and this helps move science forward.”

Vermont resident Charles Brooks, age 44, has participated in several clinical trials, including this one for the dengue treatment. “I’m interested in the scientific process. I like participating in it firsthand and doing what I can to help with developing cures for diseases,” said Brooks.

Supported by the National Institutes of Health (NIH), this trial tested a monoclonal antiviral drug called Mosnodenivir. Monoclonal antivirals are proteins engineered to stimulate the immune system to repel a specific pathogen. An oral agent like this could be deployed in dengue fever outbreaks and could be used as a prophylactic for short-term travelers or people who cannot receive a vaccine.

Many clinical trials include a placebo group—participants who receive an inactive treatment—so researchers can compare outcomes such as side effects or effectiveness against those who receive the investigational product. The volunteers attend regular follow-up visits for physical exams and to draw blood samples.

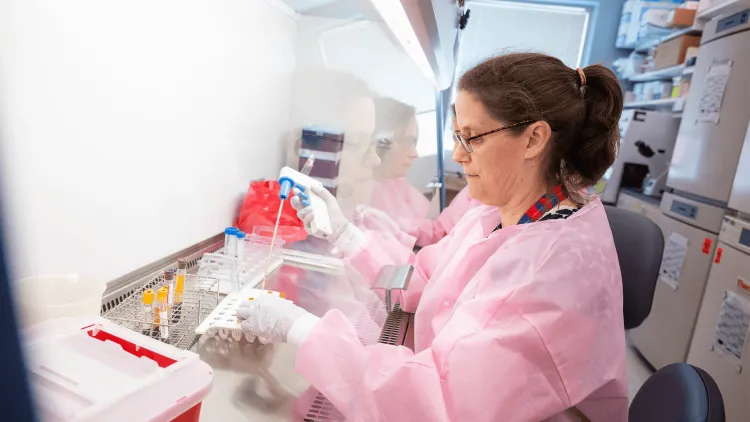

Meanwhile, on the other side of the University of Vermont campus, laboratory staff process and evaluate the blood samples. They chill the blood, spin it in a centrifuge to separate red and white cells, and examine the clear serum to count virus particles. The researchers use that information to determine how Mosnodenivir affected the volunteers’ ability to avoid dengue infection compared to the placebo and determine the doses at which it may be effective.

About 80 volunteers participated in this study for five months beginning in February 2025 at two sites: the University of Vermont Larner College of Medicine and the Johns Hopkins Bloomberg School of Public Health in Baltimore. The data, published November 26 in the New England Journal of Medicine, showed that Mosnodenivir successfully inhibits replication of dengue virus and prevents infection. Mosnodenivir will now advance to additional clinical trials to further explore whether taking this medication before contracting dengue fever affects the number of dengue virus infections in regions where dengue is endemic.

“I’m interested in the scientific process. I like participating in it firsthand and doing what I can to help with developing cures for diseases.” — clinical trial volunteer Charles Brooks

How Clinical Trials Shape Health Care

The Mosnodenivir trial is one of many clinical trials at the Larner College of Medicine, where researchers are currently investigating new vaccines to prevent Lyme disease, polio, and Clostridium difficile (the most common cause of infectious diarrhea in health care settings). Past clinical trials at Larner College of Medicine have successfully led to new medication for treating cystic fibrosis, anticoagulation treatments for COVID-19, and a COVID-19 vaccine from AstraZeneca.

Early-phase studies, such as those for new vaccines, are performed with healthy volunteers. Other trials select volunteers who have a specific disease or condition of interest, offering them access to newer, cutting-edge therapies still undergoing final testing and development. Cancer patient Rusty Ashmore participated in a clinical trial for the drug Lomustine to treat glioblastoma, a fast-growing malignant brain tumor.

“The clinical trial helped us heal and process some of the diagnosis because we knew that even if he wasn’t helped by it, there’s a piece of him that will go on to help somebody else. So, it’s a way of giving back despite the terrible situation,” said Andrea Ashmore, Rusty’s wife and caregiver.

Clinical trials with human subjects are very formal studies that follow strict federal regulations around the ethical treatment of volunteer participants, and this requires numerous facilities and well-trained staff. All studies require an informed consent process, meaning that volunteers receive detailed information about the study, have time to ask questions, and may choose to participate or withdraw at any time without penalty. A single trial at one institution will include multiple specially trained clinical trial staff, including:

- Coordinators who recruit, screen, and communicate with volunteers;

- Regulatory experts to make sure that federal regulations are met for the U.S. Food and Drug Administration and local ethics committees, called the Institutional Review Boards, to ensure the protection of participants’ rights and welfare;

- Nurses to inject vaccines or administer medications and to monitor volunteers’ health;

- Clinicians to carefully track the participants and minimize any unexpected side effects;

- A laboratory team to process and analyze the samples; and

- One or more faculty investigators who initiate and guide the study, manage the team, and scour the data.

Clinical Trial Phases

Clinical trials progress through a series of steps called phases. Typically, there are four phases. Each phase has a different purpose and helps researchers answer different questions. The phase objectives depend on whether the new product is a drug, vaccine, or medical device (for example, a new pacemaker). Depending on the scope of the study, the process can take several months or several years.

Phase 1 trials for vaccines or medications start by giving the smallest dose possible to a small group of healthy volunteers. The purpose is to study potential side effects. After dosing, the volunteers are closely monitored to see how they tolerate the treatment and to observe how it affects their immune systems. Many vaccines and medications do not advance beyond Phase 1, underscoring the need for, and importance of, early safety testing.

Phase 2 trials test experimental treatments on larger groups of people (100–300). For new drugs and devices, the purpose is to determine the treatment’s effectiveness or clinical performance. For vaccines, this phase determines the dosing schedule. Both add to the treatment’s growing safety profile.

Phase 3 trials are the largest type of study and are designed to confirm a new treatment’s efficacy. For drugs, the candidate product is compared to a past standard. For vaccines, phase 3 efficacy trials measure the ability of the vaccine to prevent a disease compared to no vaccine. Efficacy trials for vaccines may include 10,000 to more than100,000 volunteers and can take from a few months to several years to complete, depending on how much infection is circulating at the time.

Phase 4 trials are performed after the new product has been approved and made available to the public for routine clinical use. Researchers track its safety in the general population, seeking more information about the treatment’s benefits and optimal use.

Things to Consider Before Participating in a Clinical Trial

As part of the required informed consent process, a member of the study team reviews all components of the trial with each volunteer and gives them time to absorb the information and ask questions. Here are some things to investigate and consider:

- Research purpose and objectives. What do the researchers hope to learn? Who might benefit from this knowledge? Would you, personally, benefit from participating in the research? Who is funding the study, and who has reviewed and approved it? When is the study expected to be completed, and how long would your participation last?

- What volunteers will do. What kinds of medications, procedures, or tests would you have? Where will you have to go to participate? Will any of the volunteers receive a placebo or inactive treatment, and if so, would you be told if you are given the intervention being tested? How would being in this study affect your daily life or your current medical care? What happens if you volunteer to participate now, but decide to quit the study later?

- Risks involved. How much do the researchers know about the risks of the research intervention—especially if the intervention is novel or experimental? What are the short- or long-term risks, discomforts, or possible unpleasant side effects? What are the researchers doing to minimize risks, discomforts, or side effects? Does the intervention have FDA approval or oversight?

- Privacy and confidentiality. How would your biological materials (such as blood samples), data (such as test results), or other personal information be used or shared? How would your privacy and identifiable private information be protected? What could happen to you if your identifiable private information were disclosed to others?

- Financial factors. Will participating in the study cost you anything? For example, would you have to pay for certain tests or procedures? If so, would these costs be covered by your health insurance? Will there be any travel or other study-associated costs, and will researchers provide any money to cover those costs? If the research offers financial compensation, how much is offered and when would you receive it? If you were harmed while participating in the study, who would pay for the necessary medical care?

- Participation in a study does not replace routine medical care, and participants are encouraged to continue seeing their regular health care providers.

Deciding to be part of a clinical trial is a personal choice, and each person’s reasons for wanting or not wanting to participate may be different. Some join to access promising new treatments, others to contribute to research that could help future patients. Whatever the motivation, participation is always voluntary, and patients are encouraged to ask questions and make the decision that feels right for them.