Though numerous famous groundhogs saw their shadows on February 2, predicting six more weeks of winter, this long, cold season will someday come to an end. Flowers will bloom, birds will sing, and farmers will wonder about precipitation. Will it be another dry year or a wet one? How big will storms be? What management practices will best support crop yields and water quality?

UVM Extension’s Northwest Crops and Soils Program (NWCS) is on the case. At a dairy farm in the St. Albans Bay Watershed, farmers and researchers are conducting a multiyear study, called Discovery Acres, of the impacts of tile drainage and best management practices (BMPs) on runoff, soil health, and crop yields. The results will provide locally generated results that farmers can trust to help them grow healthy crops, meet state water quality requirements, and mitigate the impacts of climate change.

“The project started from farmers’ desire to understand the impacts of tile drainage on water quality—for better or worse—so they could make informed decisions and so regulations could be based on reliable data,” says project leader UVM Extension Professor Heather Darby. Though tile drainage systems have helped farmers adopt no-till, cover cropping, and other conservation practices in the finely textured, heavy clay soil in the Lake Champlain Basin (LCB), policies for and beliefs about tile have been highly contentious.

“So many of the decisions being made are based on models and findings not from Vermont data but from midwestern data,” says UVM Extension Associate Professor Joshua Faulkner, who’s working with Darby on the project. Those models and findings focus on nitrogen, not phosphorus, and don’t account for LCB soil nor for Vermont’s increasingly erratic and intensifying precipitation events.

The frequency, size, and duration of algae blooms in Lake Champlain are increasing due to high phosphorus concentrations. This nutrient and others come from agricultural field runoff and other nonpoint source pollution, such as soil erosion, lawn fertilizers, failing septic systems, and urban stormwater. Though all Vermont residents are responsible for decreasing nonpoint source pollution, the state requires that farmers meet specific standards to reduce their impacts on water quality.

Darby and Faulkner located their research on a working dairy farm to generate Vermont-based information, “to build trust with farmers around water quality data and to inform policy, programs, and education,” Faulkner says. The Bessette family’s Bess-View Farm in St. Albans was the perfect site. Decades ago, the family hired a contractor to shape a field into large berms separated by small valleys to encourage water drainage from the clay soil. These two- to four-acre micro-watersheds are perfect for collecting runoff.

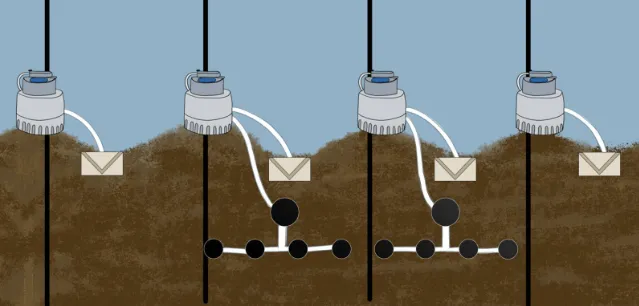

In the summer of 2020, Darby, Faulkner, and UVM Extension Agronomy Specialist Jeff Sanders began collaborating with the Bessettes to install tile drainage systems in two of the micro-watersheds, as well as solar-powered equipment to measure surface and subsurface (tile) runoff from all four fields. Some dairy and vegetable producers in the region already use tile drainage: plastic or clay perforated pipes buried 3 to 3.5 feet underground to help lower the water table to improve soil structure, growing conditions (by removing excess water from the root zone), and crop yields.

“It’s very difficult to reliably produce crops in this erratic climate, so farmers are turning to tile drainage to manage water and help provide more security,” Darby says. “We need to document benefits and tradeoffs of this practice and look at how to manage potential challenges from tile.”

In January of 2021, the Discovery Acres project became part of the multistate Discovery Farms® Program. Founded in Wisconsin in 2001, Discovery Farms® is a farmer-led, on-farm research group working to better understand the impacts of conservation practices on water and soil quality. The group, located in Vermont, Arkansas, Minnesota, North Dakota, Washington, and Wisconsin, aims to educate and improve communication among members of the agricultural community, consumers, researchers, and policy makers.

In 2021 and 2022, the Vermont research team collected calibration data from the four micro-watersheds to validate and ensure the accuracy of monitoring equipment and build a strong foundation for future statistical analyses.

Since 2023, they have been using two management practices on the four micro-watersheds and collecting data. In the North Tile (has tile drainage) and North Surface (no tile) micro-watersheds, they’re using conservation BMPs: After harvest in the fall, they’re injecting manure and planting a winter rye cover crop (without tilling); and in the spring, they’re planting corn in the living cover crop (i.e., planting green) and using an herbicide to terminate the cover crop. In South Tile (has tile drainage) and South Surface (no tile) micro-watersheds, they're using conventional management practices: After harvest in the fall, they’re broadcasting manure, tilling, and planting a winter rye cover crop; and in the spring, they’re terminating the cover crop with an herbicide and tilling, and then planting the corn. The team is harvesting corn in early fall from all four fields. Data they're collecting include nitrogen and phosphorus loads, sediment loss, cover crop biomass, soil health characteristics, and corn yield.

Little research has been conducted in the Northeast on the interactions of soil health characteristics, drainage, and BMPs, and no studies have quantified how tile drainage and multiple BMPs combine to affect water quality and crop productivity.

Discovery Acres “is a very unique experimental design and location because of the field-sized plots and individual tile drainage systems,” Faulkner says. To his knowledge, it’s the only one of its kind in the country. “The million-dollar question,” he says, “is, What is the net effect of tile drainage on phosphorus loss?” Researchers know that phosphorus and other nutrients move through tile drains, but do these drains increase the total amount of runoff leaving fields? In other words, is the total runoff different between: a) fields only with surface runoff, and b) those with surface runoff and tile drainage?

It will be another few years before the team can answer that question, both because of the quantity of data required to draw conclusions and because of extreme weather conditions. Heavy rainfall in 2023 and drought in 2025 that skewed field conditions have made it essential to have more years of data. Equipment breakdowns have also posed problems, particularly in the winter due to ice buildup. “We think winter runoff is pretty important in terms of its impact on water quality, but it’s really tough to catch those winter events,” Faulkner says.

When complete, Discovery Acres will help the local agricultural community and other stakeholders make decisions based on data generated in their own proverbial backyard. The team hopes to increase adoption rates of water quality protection practices that both protect Lake Champlain and support farm viability.

Learn more about the research at the free “Discovery Farms Multi State Webinar” on Tuesday, March 24, at 10 am Eastern Time. Research teams from Vermont, Wisconsin, Arkansas, and Minnesota will present updates and highlight new data. Register for the Discovery Farms Multi State Webinar here.

Discovery Acres in Vermont has been funded by the Vermont Department of Environmental Conservation’s Clean Water Initiative Program (CWIP); the Vermont Agency of Agriculture, Food, and Markets; and the Lake Champlain Basin Program (LCBP).

For more information, please contact UVM Extension Research Technician Claire Benning at claire.benning@uvm.edu.