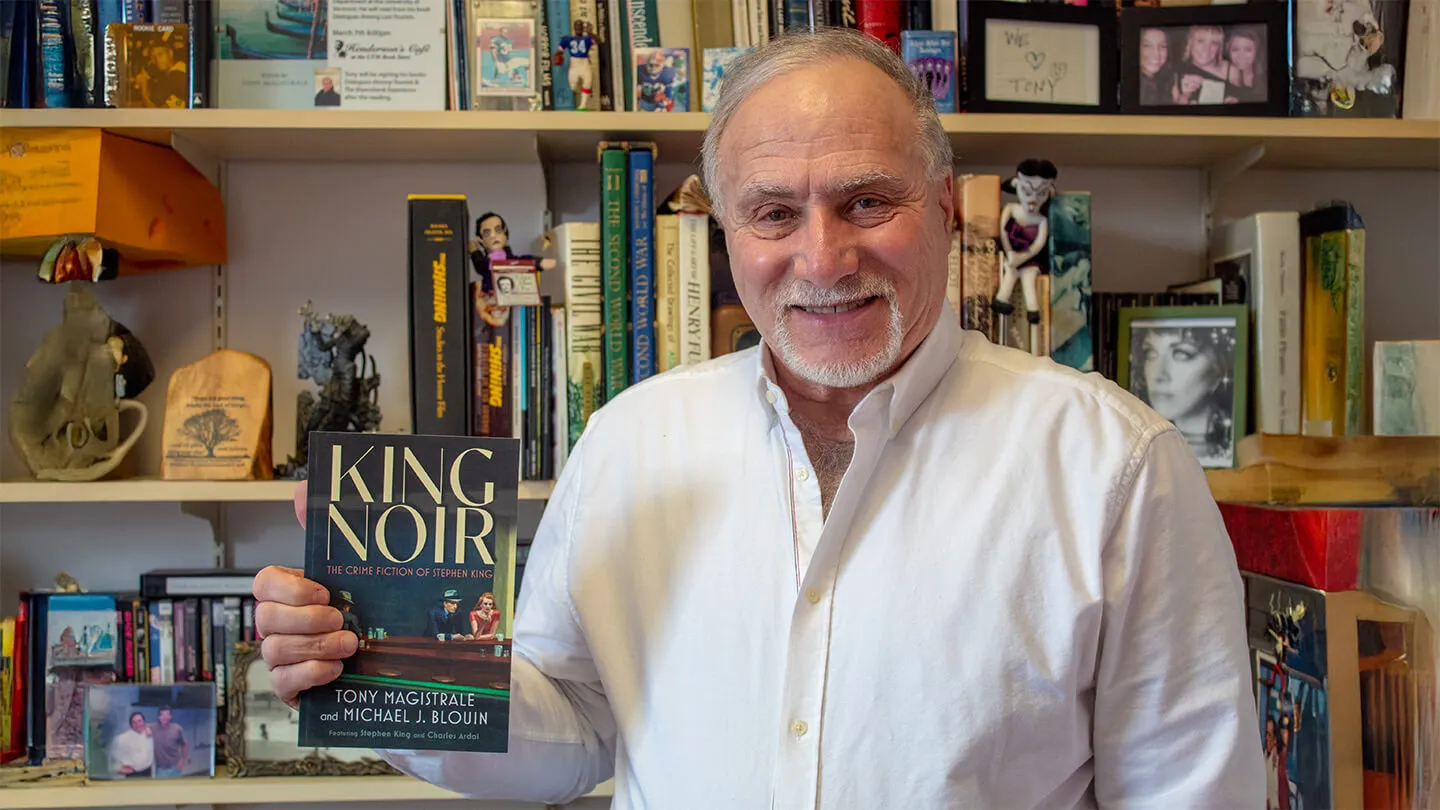

Evil clowns, haunted hotels, and vampire-infested towns—these are the kinds of blood-curdling things that usually come to mind at the mention of author Stephen King. But what about cynical detectives, hard-boiled characters, and mysterious crimes? It’s these latter elements that Tony Magistrale, Ph.D., professor and former chair of the Department of English at the University of Vermont (UVM), focuses on in his new book, King Noir: The Crime Fiction of Stephen King.

Co-authored with Michael J. Blouin, Ph.D., associate professor of English and the humanities at Milligan University (and a UVM alumnus), King Noir comes out on April 15th, 2025, and contains a never-before-published chapter by Stephen King himself on the influence of the crime genre on his writing. We sat down for a conversation with Magistrale about the book and this brand-new way of interpreting King’s canon through the lens of crime fiction.

CAS: How long have you been working with and writing about Stephen King?

Tony Magistrale: I’ve been at UVM for 42 years, and during my first year here I went to a conference where Stephen King was the guest speaker. I’d written a paper about the connection between his short story Children of the Corn and the Vietnam War. He popped into the room about midway through a session where I was on a panel and heard my paper. He was very gracious with all of us and what we had to say about his fiction.

About a year later, he did the famous Playboy magazine interview in which he said he was getting a lot of press, that it was wonderful, and that sometimes they got it right, sometimes they didn’t. He went on to say that there was this guy at a conference he went to who did a paper on Children of the Corn as a Vietnam War allegory—and that that wasn’t what he’d had in mind at all. It was a story about an Old Testament biblical presence that had infected Nebraska.

So, I wrote him a letter and said, Steve, it doesn’t matter if that’s what you intended in this story. The question is, do I have enough evidence to prove that my paper works? And we started a correspondence that eventually led to my first interview with him in Bangor, Maine.

King and I have always had an interesting and sometimes contentious relationship, because it’s not just that I’m his number one fan. There are lots of things he does that I’d like to see him do differently, and I’ve often talked to him about this. He tolerates me to a certain point.

CAS: What inspired you to explore King’s work through the perspective of crime fiction?

TM: Michael Blouin, a former graduate student of mine, contacted me a few years back and said he wanted to write a book with me, and his first thought was Stephen King. So, we ended up writing two books, one called Stephen King and American History, where we talk about various aspects of King’s fiction that connect to the American landscape specifically. And then we did a collection of essays called Violence in the Films of Stephen King.

The idea for King Noir came to us as we were tossing ideas back and forth and I said one thing I think is really interesting that no one’s ever talked about is King’s connection to crime fiction. Of course, he’s written several crime novels himself—Mr. Mercedes is perhaps the most obvious one. But there are three other books that he’s done with a hard-crime imprint in London that were published by Charles Ardai: Joyland, Later, and Colorado Kid.

So, we started to examine the way King’s own crime fiction dovetails with crime noir. Eventually, we got to talking about how this works throughout King’s fiction, that he’s constantly coming back to the model of crime fiction—of the detective specifically—through so many of his other books that are not categorized as detective or crime fiction. They still have elements, like dialogue and setting, that smack of detective noir.

CAS: How does this interpretation of King’s work differ from others’ works about his writing?

TM: The general parlance is that everybody thinks of Stephen King as a horror writer. Granted, that’s a big part of his fiction. But he also writes prison fiction, with Shawshank Redemption, The Green Mile, and even The Mist, where everybody’s trapped inside of a supermarket. He writes Westerns like The Dark Tower and The Gunslinger. I could even make the argument that he writes feminist fiction in the ’90s, with novels like Dolores Claiborne and Gerald’s Game.But nobody has ever really acknowledged the role of crime fiction in his work. And it’s huge.

CAS: How does this book differ from your own past writing about King?

TM: I think most of my attention to King’s work has focused on a kind of sociological portrait of America in novels like Pet Sematary and The Shining, I see King essentially creating or re-creating a portrait of America and a highly critical portrait of late 20th-century capitalism. This book takes us in an entirely different direction. His portrait of America is still very strong, but in his connection to detective fiction it takes us back to the ’30s and ’40s. This book really is an original thesis on how to read Stephen King’s canon.

CAS: In the book you write, “King noir is never quite as noir as it initially seems to be.” Can you touch on what that means here?

TM: I think it’s fair to say that even though King relies heavily on the noir/detective genre, he subverts it at the same time by using it in a new way. For example, in Mr. Mercedes he tells us all about the criminal from the very beginning. It’s not like we have to work our way through with the detective to figure out who’s committed the crime, because King is as interested in talking about the criminal psyche as he is the detective psyche. And this is kind of anti-noir.

There’s also a really strong tendency in King’s fiction to have happy endings, to provide solutions. Sometimes noir fiction ends without a resolution. And I don’t think that’s the case in King, except when we’re talking about the Richard Bachman [King’s pseudonym] books, which is why Bachman gets his own chapter in our book. Bachman was an opportunity for King, I think, to indulge his darker vision of life in America. And in this way, it’s very noir.

CAS: Did you discover anything that surprised you in writing this book?

TM: I was surprised by how extensively the detective genre permeates King’s canon. We found a way to talk about The Shining as a detective novel, where [main characters] Jack and Wendy Torrance are both detectives of a sort, trying to figure out what’s going on inside the hotel. We discovered this in lots of his other fiction and film, too. The film version of Dolores Claiborne is one of my favorite adaptations of King’s work. It has a detective in it, but he’s not very effective, and the people who actually discover the crime and work through it are the main characters.

CAS: What are you working on next?

TM: This latest book was a five-year project, and Michael has been a great collaborator. Having completed this is really an accomplishment. But we’re also thinking how King’s novel Carrie is now over 50 years old. Next year, the film will be 52 years old. So, Michael and I want to do a piece called “Carrie at 50.” The direction of the piece will not only be about what the novel did in terms of King’s career and its link to an American context, but also about the film. I’m particularly interested in the way in which the director, Brian De Palma, deals with issues of feminism. Is Carrie a feminist movie? So, that’s on the horizon: Carrie at 50.

I’d like to add that Michael has sparked a renaissance in me. I needed his input, his good nature, his smarts to push us forward into our own collaborative analysis of King’s work. I don’t think I could have done these three books without him.