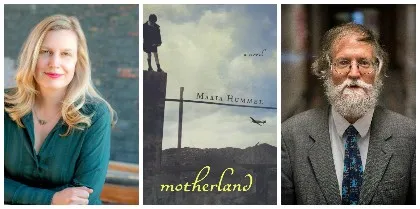

Sitting together in the English department lounge in the Old Mill, Dennis Mahoney, Emeritus Professor of German at UVM, reaches across the table and hands a faded exam booklet to his former student Maria Hummel '94. The attached paper has an “A” circled in red ink and is dated 1991. Now an accomplished author and UVM faculty member herself, Hummel receives it and smiles as if meeting a long-lost friend.

“I keep exams from superior students,” Mahoney said. “As I was going though boxes of stuff I brought back home from my office, I came across this and thought ‘well I wonder if Maria would like to have this?’”

Mahoney retired last year, and Hummel, with several novels, a collection of poetry and an MFA in creative writing under her belt, is now teaching creative writing at her alma mater. The two are connected again by their academic interests a quarter century later.

As part of his activities in Germany later this month, Mahoney will visit the University of Augsburg and deliver an invited lecture May 2 on Motherland, Hummel’s 2014 novel set in the last months of the Third Reich.

“Last summer I began reading it and about that time I received an invitation from Augsburg to give a talk as part of a lecture series on great works of literature,” he recalls. “I thought ‘Well, maybe I could do something different and talk about a contemporary work.’ Maria’s book is not only very compelling, it raises questions that are especially important today.”

Personal history

Motherland was a deeply personal project for Hummel—the novel is based on her family history in Germany during World War II. Her father, Manfred Hummel, was born in Germany in 1936, the oldest of three brothers. His mother died in childbirth when his youngest brother was born.

“My grandfather was a radiologist in Bad Homburg, a place that is, loosely speaking, the setting for the book,” Hummel said. “He actually put an ad in the local newspaper: ‘doctor needs wife.’”

The woman who answered the ad—Hummel’s step-grandmother—married into a family with three boys under six years of age shortly before her new husband was deployed to Weimar to work at a military hospital. Largely strangers, the couple carried on a wartime correspondence. In her letters, the new wife and mother tried to keep a stiff upper lip in the face of air raids, food shortages, and a terrible accident that cost Hummel’s father all the fingers on one hand.

As the Eastern Front collapsed from the invading Soviets, Dr. Hummel bicycled his way west to reunite with his family. Before crossing into American lines, he hid a packet of letters from his wife in the attic of a house in Thüringen.

“We didn’t know about the letters until my uncle, who was still living in the family home, was contacted by a couple who were renovating the house in the 1980s,” Hummel said.

By that time, Hummel was growing up in Burlington and her father was teaching German at Rice High School. She was inspired to write about the story, but the complexity of the subject matter—the tension between the public life of Mitläufer (Germans who were not enthusiastic Nazis, but not active public resistors to the Reich), and the private challenge of survival—was something she needed time to think through.

The main characters in Hummel’s novel, Frank and Liesl, are loosely based on the lives of her grandparents. Unlike most wartime novels, the book is largely about the home front, describing the parents’ complicated choices to protect their family in the midst of societal collapse.

“My grandparents died when I was young,” Hummel writes in the book’s afterward, “but they struck me as generous and kind, any my grandmother rather courageous for single-handedly raising three small kids at such a harrowing time. I obsessed over the idea of complicity, how ‘good’ people could nonetheless participate in one of the most brutal regimes in contemporary history.”

It was a personal crisis that served as one access point for telling the story. Hummel’s oldest son fell ill with a rare gastrointestinal disorder when he was nine months old and was seriously ill during the time she was working on the book. The story became a kind of refuge as she dealt with own anxiety, and the prism through which she developed another character in the book, the middle son Ani, whose emotional troubles put him at risk for admittance to Hadamar, a notorious psychiatric hospital known for mass sterilizations and murder of Lebensunwertes Leben (“those unfit to live”).

“You wouldn’t think going to such a terrible place in history could be an escape, but I think it served as a way for me to go more deeply into feelings I was experiencing myself by focusing on this other story,” Hummel said.

New meanings

Hummel took some German in high school from her father but tells Mahoney that the ability to read primary source material came from his classes.

“You had us actually reading books in German," she says to Mahoney, "so I think, even though I had to also rely on translated stuff, understanding of German culture and the ability to navigate primary source material came from your courses.”

For his part, Mahoney tells his former student that her novel has relevance for today.

“Part of my lecture will be the observation that what a lot of Germans were seeing in 1933 and 1934—we are seeing today,” Mahoney said. “Which is not to say the U.S. resembles Nazi Germany, but those chilling reminders—like the posters on campus that recently appeared saying ‘stop importing problems, export solutions’—create a climate where these things are accepted or even welcomed. For me, your novel has raised questions in 2018 in ways you couldn’t have anticipated in 2014 when you wrote the book.”