By: Gabriela Bucini

Reflections on a two-part workshop given on April 6 and 15, 2021 by the Agroecology Support Team of the McKnight Foundation Collaborative Crop Research Program.

The West Africa (WAf) CoP is a dynamic group and an example of a community with a perspective on the future, which extends across local and global horizons. Agroecological transitions are actively taking shape in Burkina Faso, Mali and Niger, stemming from experience and knowledge in agricultural practices, nutrition and market activities. Research methods also have been changing over the years to engage project actors and farmers in collaborative participatory learning and to support innovations that build on local resources. Furthermore, the CoP has catalyzed actions directed at creating gender equality and social justice.

When the WAf CoP gathers, everyone’s work becomes a shared experience and an opportunity for co-learning.

In April 2021, the Agroecology Support Team (AES) proposed a workshop on the theme of agroecological transitions (AET) through a lens of agroecological principles and personal values.

The goal was to strengthen projects’ confidence in their own knowledge and to ease familiarity with the AET as a process. The participants engaged with two main activities: 1) contextualizing agroecological principles to make them actionable within local realities; and 2) envisioning an agroecological transition for a desired change grounded in contextualized principles, personal values and local resources. Agroecological principles can inspire and orient us, but they become alive only when the actors enrich them with their words and realities. Assimilating practical references and examples, the definition of local farmers can ground action more easily.

A participant said that the recognition of the knowledge in hand of a community, and the exchange of this knowledge, are necessary to let the transition process emerge. In Niger, poverty is a big problem that agroecology must face but there is also a socio-cultural tradition of community work that can be a key resource, said another participant. Some communities organize themselves to support vulnerable people. Valuing this culture, we want to support communities that meet, find their own solutions and take initiatives around integration of people, animals and nature – a work of peace. In this way we can make synergies tangible and advance in the transition. Not forgetting that poverty calls for concreteness, a participant reminded us of producers’ weak purchasing power, which limits the effective application of agroecological technologies. He appealed to the necessity of activities that bring revenue and security. The agroecology transition requires lots of action and time. It needs to deliver outcomes.

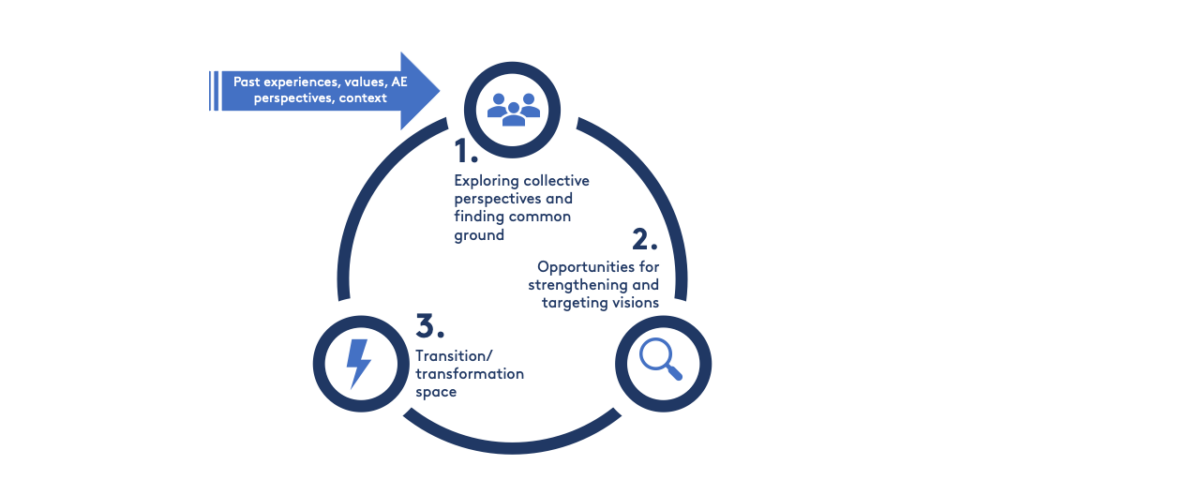

The AES team proposed a schematic of an agroecological transition (AET) process (Figure 1) to facilitate an AET visioning activity. The process is broken up into three phases along a circle, suggesting the natural cyclic motion of transitions. It tracks the phases of building a common ground with our transition companions, focusing on a few specific intentions and then acting, always remembering to circle back and reflect on learned lessons, renew our values and principles and direct our attention to our next action step.

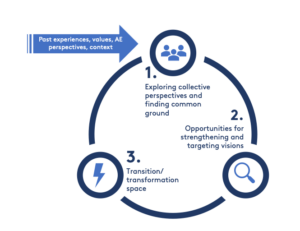

The compelling story of the farmers from The Shashe farms in the Runde catchment area of Zimbawe provided a concrete example of a value- and AE principles-based vision of an agroecological transition. This transition, led by Elizabeth Mpofu, engages multiple actors and disrupts narratives of failure (or problems) by reshaping them into narratives of assets and participatory action. We can read this story through the lens of the AET process (Figure 2). Mrs E. Mavedzenge, local farmer, says “We don’t allow water to just run through our fields; we keep every drop of water. We harvest rainwater which flows from the road and, as it rains, into the contours that we have built.” We recognize phase 1 as the people from the Shashe farms and Elizabeth Mpofu come together with their knowledge and core values, and use agroecology to create change. We find phase 2 in the focus on soil aridity and phase 3 with the synergy of principles guiding action (Figure 2).

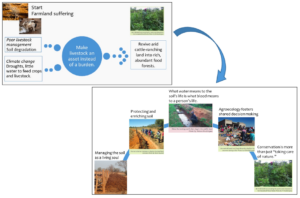

Inspired by the Zimbabwean example, the workshop participants were invited to work in groups by country and create a vision for an AET that starts from a local problem and can be turned into an asset through a transformative process and collaborative response. The groups’ visions were ambitious enough to be exciting but also achievable with local resources and the CCRP program’s support. They were also far enough into the future to work towards keeping faith and commitment. The groups aligned their visions and values to agroecological principles and showed attentive sensitivity to the CCRP principles as well. Indeed, co-learning, gender equity, diversity, support of better livelihoods and sustainability were all integral part of the visions.

The workshop participants showed that agroecological transitions are possible. In the AET visioning, groups identified new synergies among projects and/or strengthened existing ones seeking to have a more holistic view of the work and benefit from expert complementarity. The actions proposed relied on local knowledge, resources and adaptive capacity (examples in Figure 3). Groups contextualized the FAO agroecological principles using words that reflected local experience and needs. For example, the principle of resilience was expressed as “ensuring good nutrition and diversified income generation in a context of climate variability”. This specificity resulted in more realistic and actionable visions.

The majority of the presentations emphasized the interconnection among science, practice and movement. The explicit inclusion of socio-economic or socio-political factors, in the visions, was a sign that agriculture is seen in its human dimension, too. For example, the principles of food sovereignty and diversification were related to the political aspects of control over seeds and choice of crop varieties. Those two principles are also key entry points for supporting and promoting women’s equality in terms of economic independence, access to education and decision-making processes at both the family and broader scale levels.

The participants clearly highlighted the influential role of regional and national policies on the future of food systems, agroecological practices and education in their countries. They sought a voice to influence national decisions and were aware of the importance for these decisions to be formulated with the participation of those intended to adopt the agroecological practices.