A

Discussion of Agriculture in Townshend, Vermont

Kaitlin

O'Shea, October 2009

Historic

Preservation Program, University of Vermont

Historical

Narrative

Townshend, Vermont is located in southeastern

Vermont in Windham County in the Connecticut River Valley. On June 20, 1753 the state

of New

Hampshire chartered Townshend to John Hazelton and sixty-three others.[1]

In 1840, Townshend increased by annexing Acton.[2]

At that time, Windham County was part of

Cumberland County, which was not

divided into Windham, Windsor, and Orange counties until February 1871.[3]

Typically, four villages are typically included as a part of Townshend:

West

Townshend, East Townshend (or Townshend Village), Harmonyville, and

Simpsonville. In

early gazetteers

such as that of James H. Phelps, the town is discussed according to its

division of school districts.[4]

This is also

seen on the F.W. Beers Atlas of Windham County, Vermont, 1869.[5]

West River is the main river

running through Townshend with several brooks:

Acton, Fair, Negro, Joy, Mill, Fletcher, Simpson, and Acton. These

water

sources provide fresh water for domestic uses and irrigation if

necessary.[6]

River valleys provide excellent

arable land and the hillside provides grazing

ground.

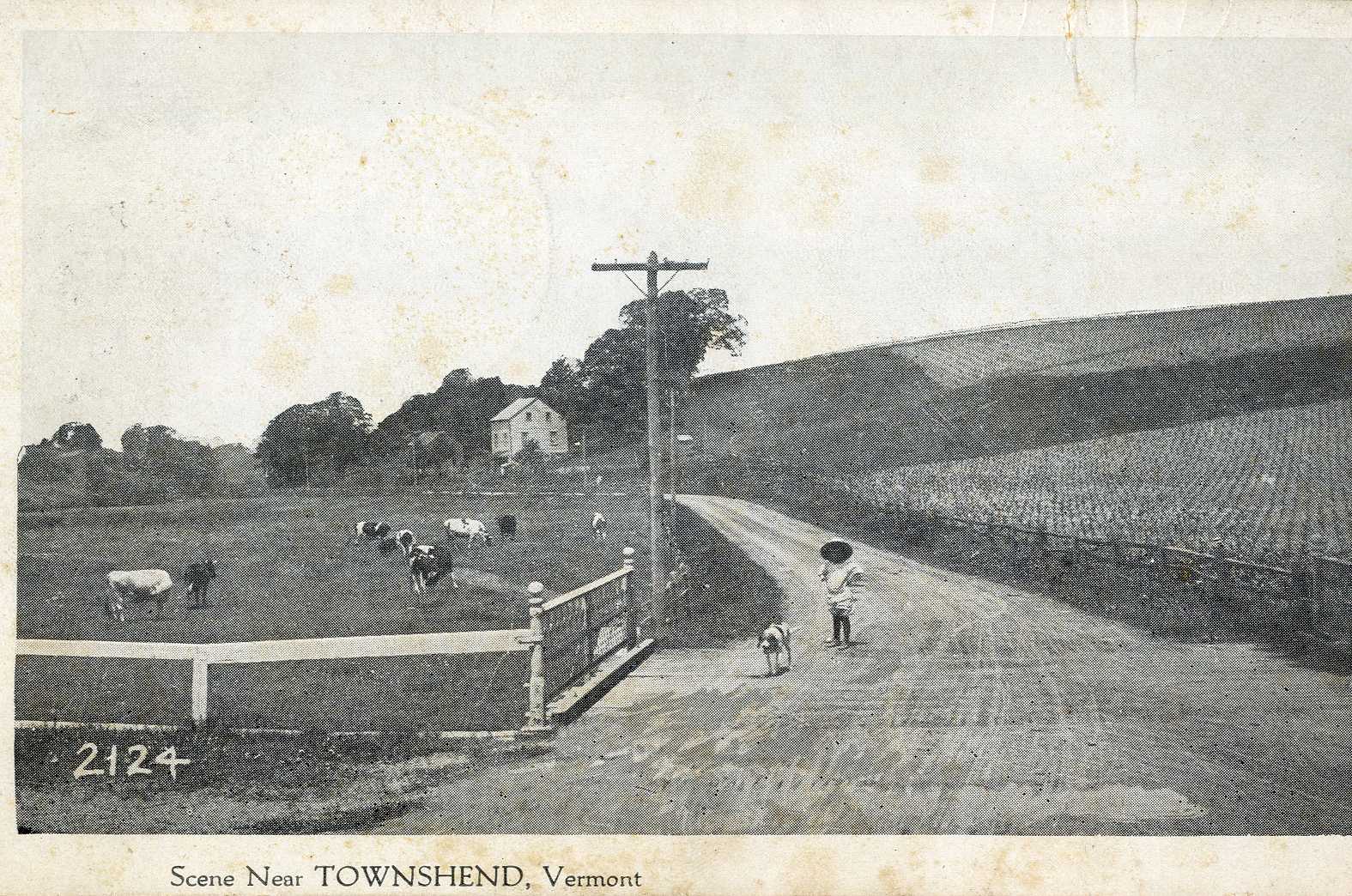

Figure 1: A

farmstead near Rattle Snake

Mountain shows the rugged terrain of Townshend.

Courtesy

of the University of

Vermont Libraries Special Collections.

Early surveyors of Townshend discouraged settlers

due to the rocky terrain and inhospitable farming land;[7]

yet, people moved to Townshend regardless and farming became the

primary

occupation of the residents. Townshend reached its peak population in

1820 with

1,406 people.[8]

Zadock Thompson's A Gazetteer of the

State of the Vermont (1824) discusses the early agricultural

activities of

Townshend, showing that the early farmers found success amongst the

mountains

and valleys.[9]Thompson

writes that industrious farmers are able to have "their barns filled

with hay and flax, their granaries with corn, wheat, rye, oats,

barleys, peas,

and beans and their cellars with the best of cider, potatoes, turnips,

beats,

onions, and other esculent vegetables."[10]

In addition, other notable crops and products included apples, lumber,

butter,

and cheese.[11]

Aside from pure agricultural

activities, Townshend was supported by

agricultural related activities including blacksmiths, gristmills,

furniture

makers, tanners, sawmills, a harness shop, and the usual town

businesses such

as a general store, a hotel, a millinery, a tinsmith, a drug store, and

a

carriage shop.[12]

The first

blacksmith, General Fletcher, began operations ca. 1770.[13]

Mills represented some of the

early businesses, the first one beginning

operations in 1782.[14]

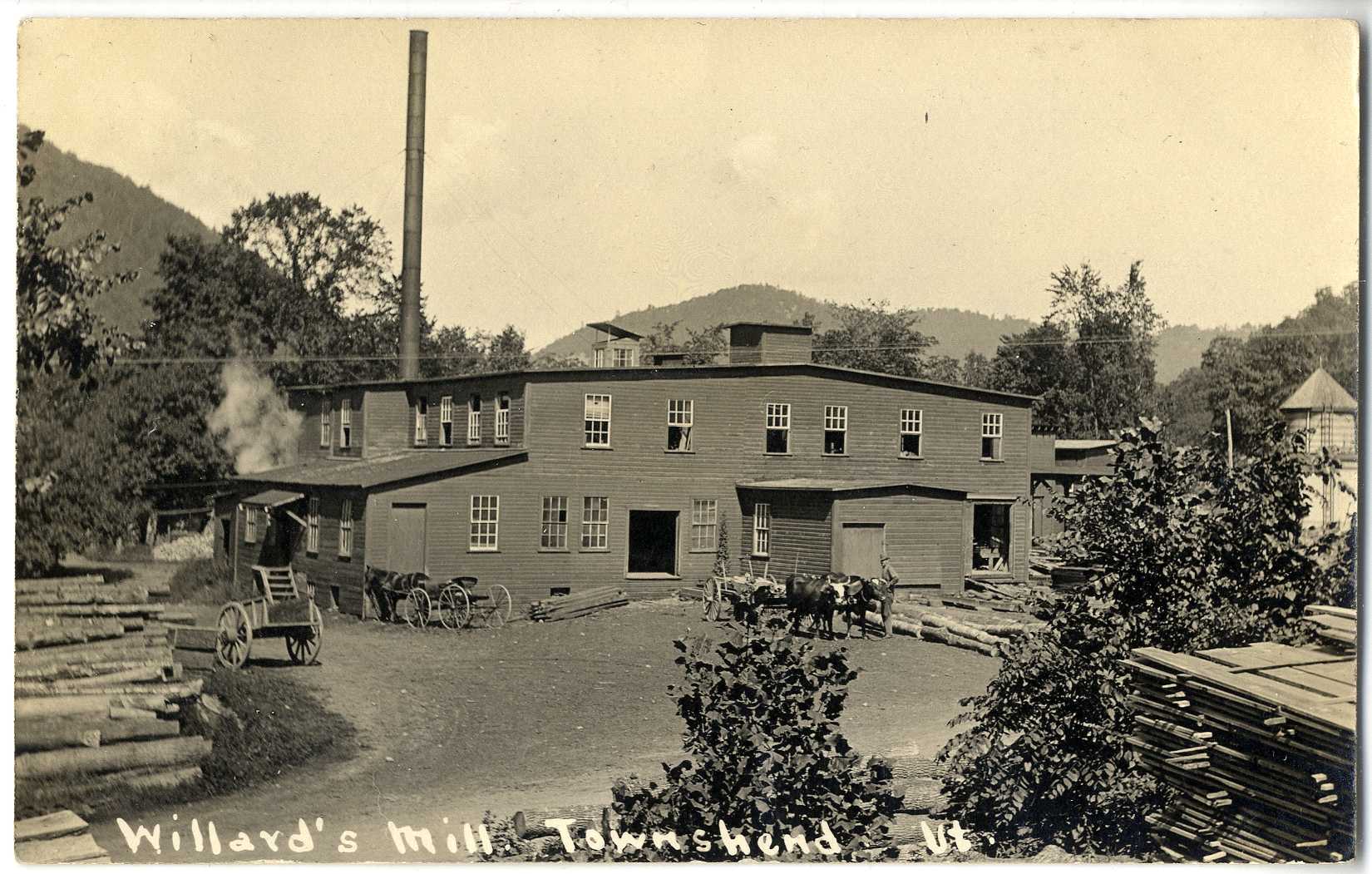

Figure 2: A 1910

postcard of Willard's

Mill.

Courtesy

of the UVM Libraries Special Collections.

Little information of the earliest days (late

1770s) of Townshend farming is available; that information would have

to be

obtained by individually investigating the extant barn structures and

perhaps

deed records. For instance, structures would have to be examined in

order to

determine the methods of construction looking for timber framing, hand

hewn

timbers, and scribe rule markings, which would indicate the late

1700s/early

1800s for building construction.[15]

However, Phelps'

tables of Grand List Statistics for

Townshend (for taxation purposes) address some agricultural

activities and

other statistics from 1802 – 1841.[16]

Summarized, his calculations

demonstrate that with some dips and regeneration, overall, cattle

ownership

reached its height (between those years) in 1833. Sheep continuously

increased,

reaching the greatest number in 1841. Overall, sheep farming in Vermont

reached

its peak in the early 1830s;[17]

thus,

Townshend saw success longer than most parts of the state.

Many products harvested or made on family farms

could be bartered locally, with some of the earliest exports of maple

sugar and

wood. Large sheep farms emerged in the 1820s -1830s as did large-scale

potato

farming.[18]

A few decades later, the 1860 and 1880

U.S. Census of Agriculture reveal that many of the 1820s farming

activities, as

discussed by Zadock, are still in place. Farmers of Townshend supported

themselves and their families primarily from the land, with a few

specialized

crops or products that would help to support their livelihood. Records

of the

1860 and 1880 agricultural census show that the most prevalent crops

were Indian

corn, Irish potatoes, butter, maple sugar, wool, and orchard products.[19]

In both years, farms grew at

least one cereal crop, typically oats, wheat, or

rye. milch cows, sheep, and oxen outnumbered horses and swine. Based on the census records,

productions

appeared steady with few differences. For example, while butter was a

very

popular dairy product in 1860 and 1880, cheese was much more widespread

in

1860.[20]

Figure 3: Oxen

pulling felled trees

through the village of Townshend, VT, 1913.

Courtesy

of UVM Libraries Special Collections.

The Hamilton Child's Gazetteer

provides a helpful look at Townshend agriculture in

1884. The largest

concentrations

farms lied along the main roads (today what are VT Routes 30 and 35),

with many

on the western side of town near Acton Brook and the West River. The

most

common farm specifications included sugar orchards, sheep, and dairy.[21]

Sheep and wool production could be found most commonly in the western

half of

town while sugar orchards mainly filled the eastern side of town.[22]

In Hamilton Child's Gazetteer only

a few farmers were listed

as owning apple orchards, yet according to the 1880 census most farms

had apple

trees and produced many bushels of apples that year.[23]

While trends in Vermont represent a decrease in

sheep farming and wool products in the mid 1800s and an increase in

dairy

farming in the mid to late 1800s,[24]

a 1939

Works Progress Administration report analysis found that the number of

cows and

sheep decreased from 1850 onwards; although after 1880, the number of

sheep

diminished drastically and the number of dairy cows saw a slow, steady

decline.[25]

As the market changed, Vermonters focused on a diversity of products

that could

be sold in the urban areas, which was possible due to the expansion of

the

railroad. The Rutland Division of the Central Vermont Railroad opened

in

December 1849 and passed through Windham County, though the railroad

faced many

construction challenges and the branch from Brattleboro to South

Londonderry

did not open until 1880.[26]

Products

and crops included milk, eggs,

potatoes, corn, cereals, and fruits.[27]

Townshend generally follows the overall

agricultural history of Vermont, with some differences. For example,

the 1860

and 1880 censuses do not list tobacco or hops, which both made their

way into

Vermont agriculture.[28]

Overall,

the agricultural production and land in Townshend reached its peak in

1860, but

has since declined. This change can be seen by looking at the number of

farms

in Townshend in 1860 (183), 1880 (157), 1935 (78), and 1945 (69).[29]

Although this decrease in the number of farms can be accounted for by

the fact that

some farms were combined, thereby increasing the acreage, the overall

agricultural activities did decrease[30]

A report on the Agricultural Trends

written for the Works Progress Administration in 1939 includes charts

that plot

the number of farms and livestock in Townshend. Comparing 1850

to 1935, the numbers of milch cows, oxen, other neat stock, horses,

hogs, and

sheep declined, though hens, unrecorded except in 1880 and 1935,

increased from

2,161 to 3,289.[31]

This

indicates that chicken and egg production became an important part of

the

agricultural economy. Beyond the 1940s and 1950s, trends across the

state of

Vermont show a sharp decrease in agriculture, particularly with the

development

of farming as a corporate big business. Family-owned farms, in the

state and

across the nation, could not compete.[32]

Figure 4: Dairy

cows in the pasture near

Townshend, VT, ca. 1930.

Courtesy

of UVM Libraries Special

Collections.

Modern

Townshend

The modern landscape and built environment of

Townshend certainly indicates that the town has an agricultural past; a

windshield survey conducted in September - October 2009 of Townshend

found approximately

180 properties to have at least one agriculturally related structure,

whether a

large ground stable barn or a small greenhouse. However, not all of

these

structures were historic, and some historic structures may have been

clad in

new siding and meticulously maintained. A windshield survey lacks that

depth. Some

historic activities

remain visible on the landscape, such as dairy farming. Most noticeably

there

are small scale diversified or specialized farming activities in

Townshend. For

instance, farms advertise maple sugar, alpacas, and pumpkins. One farm appeared as a

hobby farm,

raising emus.

Furthermore, while sugar production and growing

potatoes were two of the most common agricultural endeavors, very few

related

structures were seen during the survey. Historic maple sugar houses are

no

longer in use, many are dilapidated. Some buildings may no longer be

standing

due to common fires.[33] Farms

advertise maple sugar,

which indicates that farmers have new structures or other methods for

maple

sugar production.

Figure 5: A

dilapidated maple sugar house

at Peak Mountain Farm in Townshend, VT.

Photograph

by author, October

2009.

In the case of potato storage, they may have been

out of sight from the public road. However, for those barns standing,

many

appear to be in use, though often the use is currently for storage of

belongings or vehicles. Barns in the villages have been converted to

antique

stores, garages, and in about five visible cases, barns have been

rehabilitated

into a house or business and office space.

Townshend,

VT remains a primarily rural town as of October 2009 with small

villages,

Townshend being the largest. The southwestern portion is largely

Townshend

State Forest, a Vermont State Park. The southeastern portion reveals

new

development just south of Crane Mountain to the east of Harmonyville. Comparing historic and

modern maps

reveals that this area had not seen development.

A 1958 road map shows an unimproved

road through the area,

though the 2000 map reveals small, short, winding roads.[34]

New construction is still occurring. Overall, the farms do not suggest

high

agricultural activity; there is not evidence for the great quantities

of apple

orchards from the 1880s. A few large stable barns suggest prior using

for sheep

and cattle. However, the extant barns reveal a recent link to

agricultural and

in many cases, residents are maintaining their barns, adapting them for

a

current use and showing their connection to their heritage.

Figure

6: A rehabilitated barn

converted to a dwelling at 2557 Grafton

Road, Townshend, VT.

Photograph

by author (October 2009).

Suggestions

for Further Research

Due to the limitations of this project and the

vast amount of primary sources available, one avenue for research is to

analyze

Phelps' discussion of Townshend residents and their properties

mentioned. As

Phelps writes of construction dates

and alterations to their property, including barns; there is much

information

to be discovered. Unfortunately, individual properties are identified

by occupants

in 1877 and not by the modern construct of addresses.[35]

Phelps discusses these properties in relation to the districts of the

town,

similar to the F.W. Beers Atlas. Seeing as Phelps' Gazetteer was

published in

1877, many of the names discussed correlate to the Beers Atlas of

Windham

County of 1869. Thus,

there is

invaluable information. Complemented by deed research to trace the

property

owners' names and matching them to Phelps and Beers would result in an

understanding of the individual farms. Phelps

even accounts for properties that have been moved or

demolished. This study, given appropriate attention, could accurately

place the

agricultural activities of Townshend.

[1]

Hamilton

Child, Gazetteer

and Business Directory of Windham County, VT, 1724-1884 (Syracuse, New York: Journal

Office, 1884), section 304, 20-21.

[4]

James H.

Phelps, Collections Relating to the History

and

Inhabitants of the Town of Townshend, Vermont, Part

II (Brattleboro, Vermont: Geo. E. Selleck, 1877).

[5] F.W. Beers, Atlas

of Windham County, Vermont (New York: F.W. Beers, A.D. Ellis,

& G.G.

Soule, 1869).

[6]

James H. Phelps, Collections

Relating to the History and Inhabitants of the Town of

Townshend, Vermont, Part II

(Brattleboro,

Vermont: Geo. E. Selleck, 1877), 50.

[7] Hamilton Child, section

304, 23.

[8] Zadock Thompson, Gazetteer of the State of Vermont, Contains

a Brief General View of the State: A Historical and Topographical

Description (Montpelier:

E.R. Walton, 1824), 310.

[13] James H. Phelps, 160.

[15]

Thomas D. Visser, Field

Guide to

New England Barns and Farm Buildings (Hanover, New

Hampshire: University

Press of New England, 1997), 9-19. During

a windshield survey conducted of Townshend in

September-October 2009,

the author found approximately 20 English barns, which would be a good

place to

begin investigations.

[16] James H. Phelps, 240-246.

[17] Agricultural

Resources of Vermont, Multiple Property Documentation Form,

National

Register of Historic Places (Montpelier, Vermont: Vermont Division for

Historic

Places, 1991), E6.

[18] Agricultural

Resources of Vermont, Multiple Property Documentation Form,

E6.

[19] U.S. Bureau of the Census,

Agricultural Census,1860,

1880.

[21] Hamilton Child, 486-495.

Analysis based on the

Town of Townshend section in the Business Directory of Windham County,

in which

individuals are listed with their occupation and address by road. Those

listed

as farmers sometimes have a specific type of farming listing, which was

utilized in this discussion.

[23] Ibid.; U.S. Bureau of the

Census, Agricultural

Census, 1880.

[24] Agricultural

Resources of Vermont, Multiple

Property Documentation Form, E7.

[25] Works Progress

Administration, Agricultural Trends in

Townshend, VT, Official Project No.

665-12-3-56 (Burlington, Vermont:

The

Agricultural Extension Service, University of Vermont and State

Agricultural

College, September 1939), 5.

[26] Hamilton Child, 46-49.

[27] Howard S. Russell, A Long Deep Furrow, with foreword by

Wayne D. Rasmussen (Hanover,

New Hampshire: University Press of New England, 1976), viii.

[28] Agricultural

Resources of Vermont, Multiple

Property Documentation Form, E7.

[29] U.S. Bureau of the Census,

Agricultural Census,1860, 1880; Farm

Census for the Towns in Vermont Based on the Bureau of the Census

Unpublished

Data, Jan. 1, 1945 (Burlington Vermont: University of

Vermont and State

Agricultural College Cooperative Agricultural Extension Service, 1946

1935

figure from WPA report, 1946) available at UVM Libraries Special

Collections.

[30] Works Progress

Administration,

Agricultural Trends in Townshend,

VT, 5.

[32] Agricultural

Resources of Vermont, Multiple Property Documentation Form,

E29.

[33] Thomas D. Visser, 180.

[34] Townshend Road Map with

alterations, 1958 from

the Town Highway Map Archives of the Vermont Agency of Transportation,

http://www.mtbytes.com/vtrans/, accessed 10/25/2009; Road Names in

Townshend,

VT, 2000, provided by the Windham Regional Commission.

[35] This warrants a much more in

depth history of

Townshend properties, in which many properties could be identified

through deed

research and be paired with PhelpsÕ history. It does not discuss the

use of a

building beyond house or barn.