Registers

We mentioned earlier that flip-flops are synchronized sequential circuits, with actions triggered by the leading edge of a clock pulse. We also noted that the fetch-decode-execute cycle (like many other processes in a computer) depend on strictly regimented temporal execution—everything must proceed in lockstep. This includes writing values to registers and reading values from registers. Registers, of course, are fundamental components of a CPU, where they are used to store data, instructions, and memory addresses. Registers are essential for implementing the program counter, general-purpose registers, and pipeline registers in modern processors.

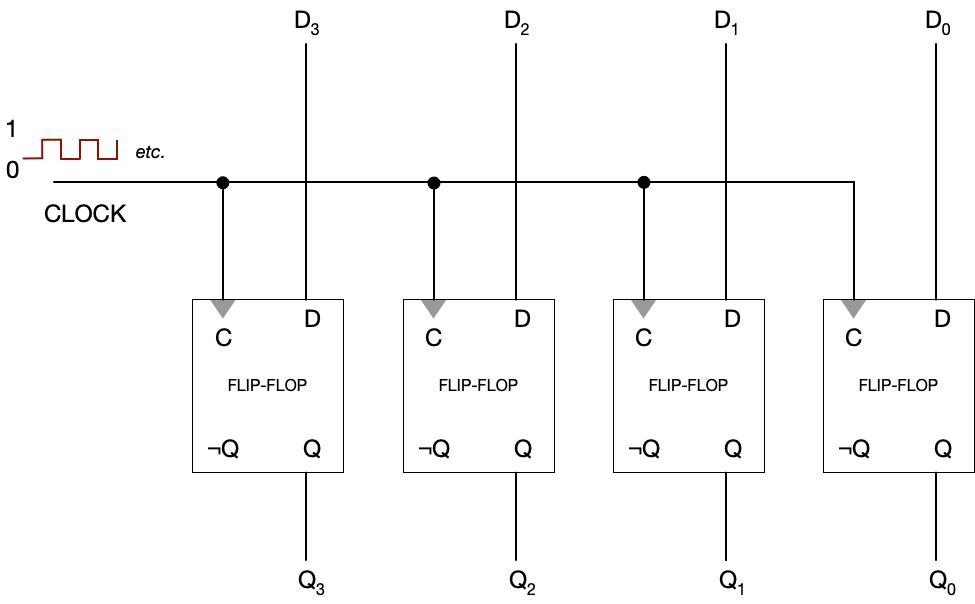

By combining multiple flip-flops, we can create a register, which stores a multi-bit value. A 4-bit register, for example, uses four flip-flops—one for each bit. A 32-bit register uses 32 flip-flops, and a 64-bit register uses 64.

For example, suppose a 4-bit register currently holds the value 1010. If new data 1100 is applied to the inputs, the output will not immediately change. Instead, the register will update to 1100 only at the next rising clock edge. This property ensures that all registers in a CPU update simultaneously, keeping the processor synchronized. In other words, a CPU register is just a bank of synchronized flip-flops, with each bit stored in one flip-flop. This allows the processor to reliably hold and update binary values in lockstep with the clock.

Here’s a 4-bit construction (larger constructions only differ in the number of flip-flops, data lines, and outputs).

In our diagram, we use a rectangle as a symbol for a flip-flop with a small triangle indicating the clock input. We connect all the clock inputs to a common clock line. Each flip-flop has its own data input, and produces its own output. But with all flip-flops wired to the same clock, they all operate synchronously.

Now, you might ask: Why aren’t we using the complementary output, \neg Q? Good question. The flip-flop naturally produces the complementary output, but we don’t usually use it. It is necessary that we have it internally so that we can construct the appropriate cross-coupled feedback loop. But in most use cases, its value isn’t needed, so it’s there but not read. There are some cases where we would use it, for example, when we specifically wanted the inverted output of a register bit. In that case, we’d read from the complementary output rather than adding another inverter circuit. But in the main, these values aren’t used.

© 2025 Clayton Cafiero.

No generative AI was used in writing this material. This was written the old-fashioned way.