Inside your computer

Inside your computer

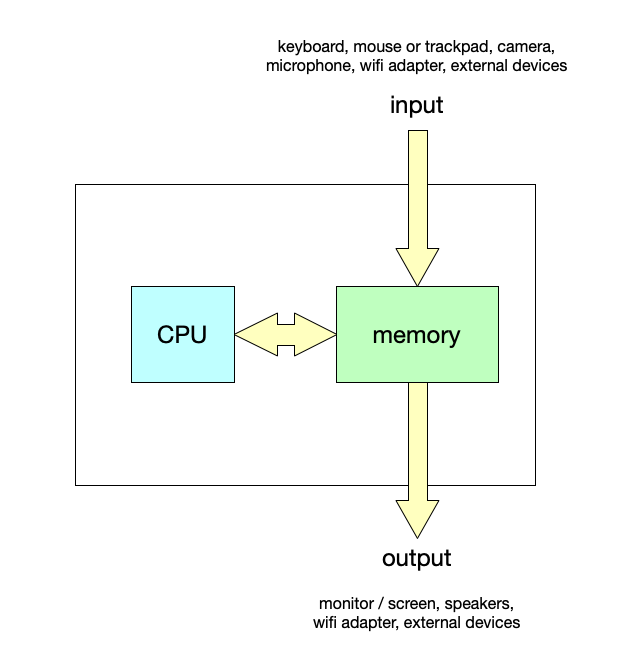

von Neumann architecture

Let’s take a look inside a typical personal computer.

Of course this is quite a simplification—there’s a lot more to it—but notice that this is, essentially, the von Neumann architecture.

- CPU (central processing unit)

- memory

- various input and output devices (or interfaces)

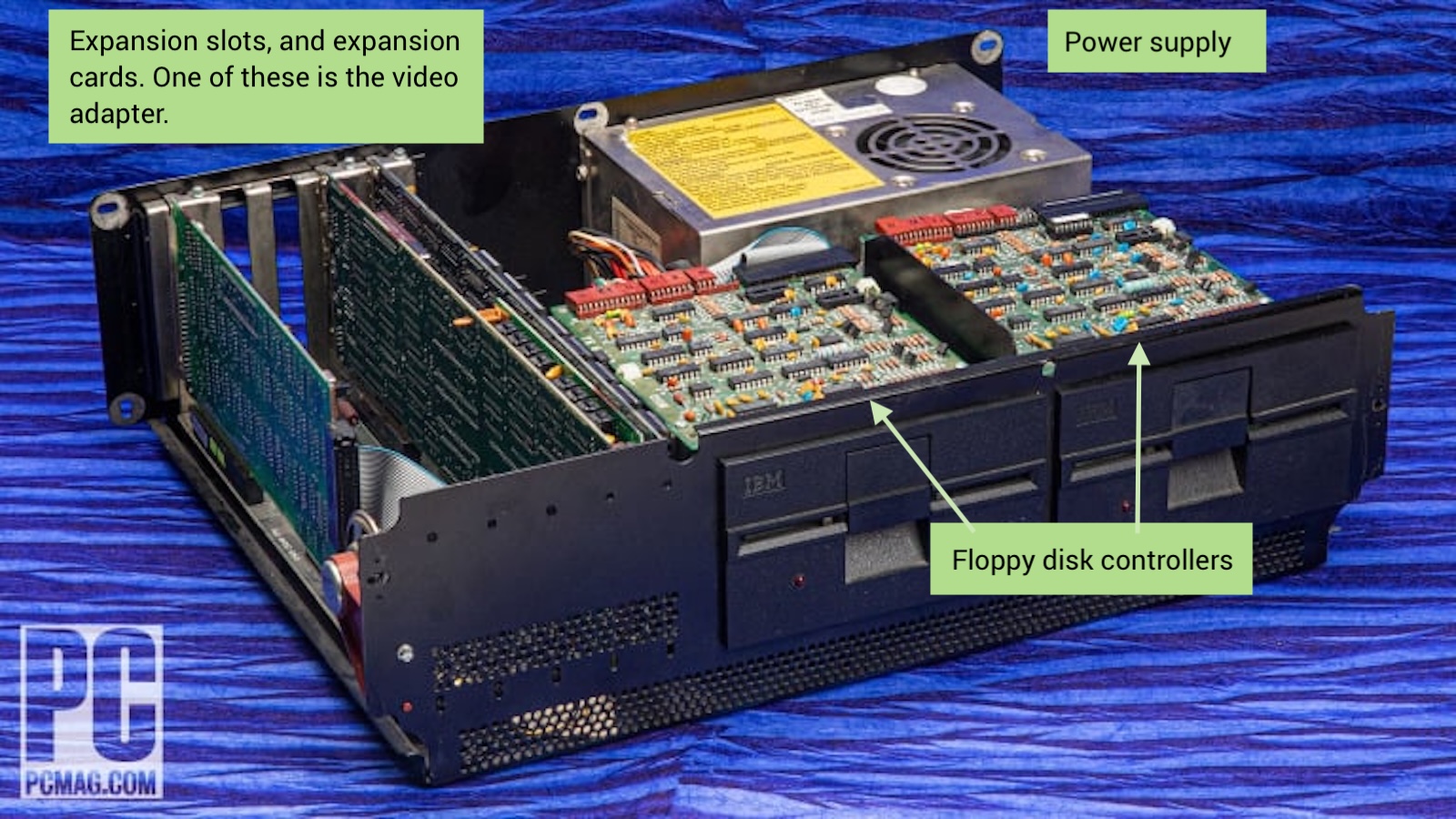

An early “personal computer”

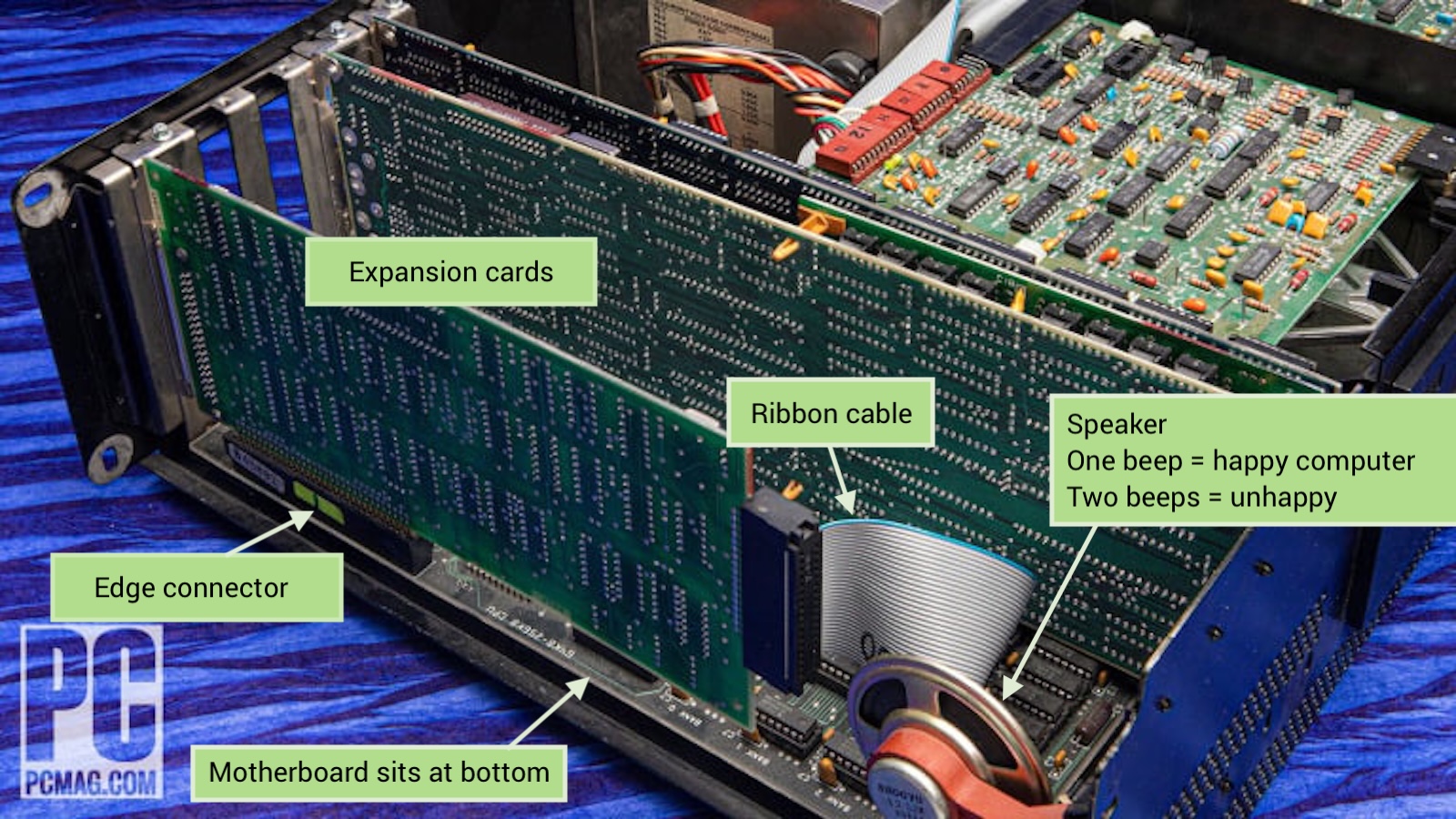

It used to be the case that there’d be a so-called “motherboard” or main system printed circuit board, and then separate “daughter” circuit boards (also called expansion boards) for specialized functions (like graphics adapters or sound adapters), which would connect via a broad pathway called a “bus”.

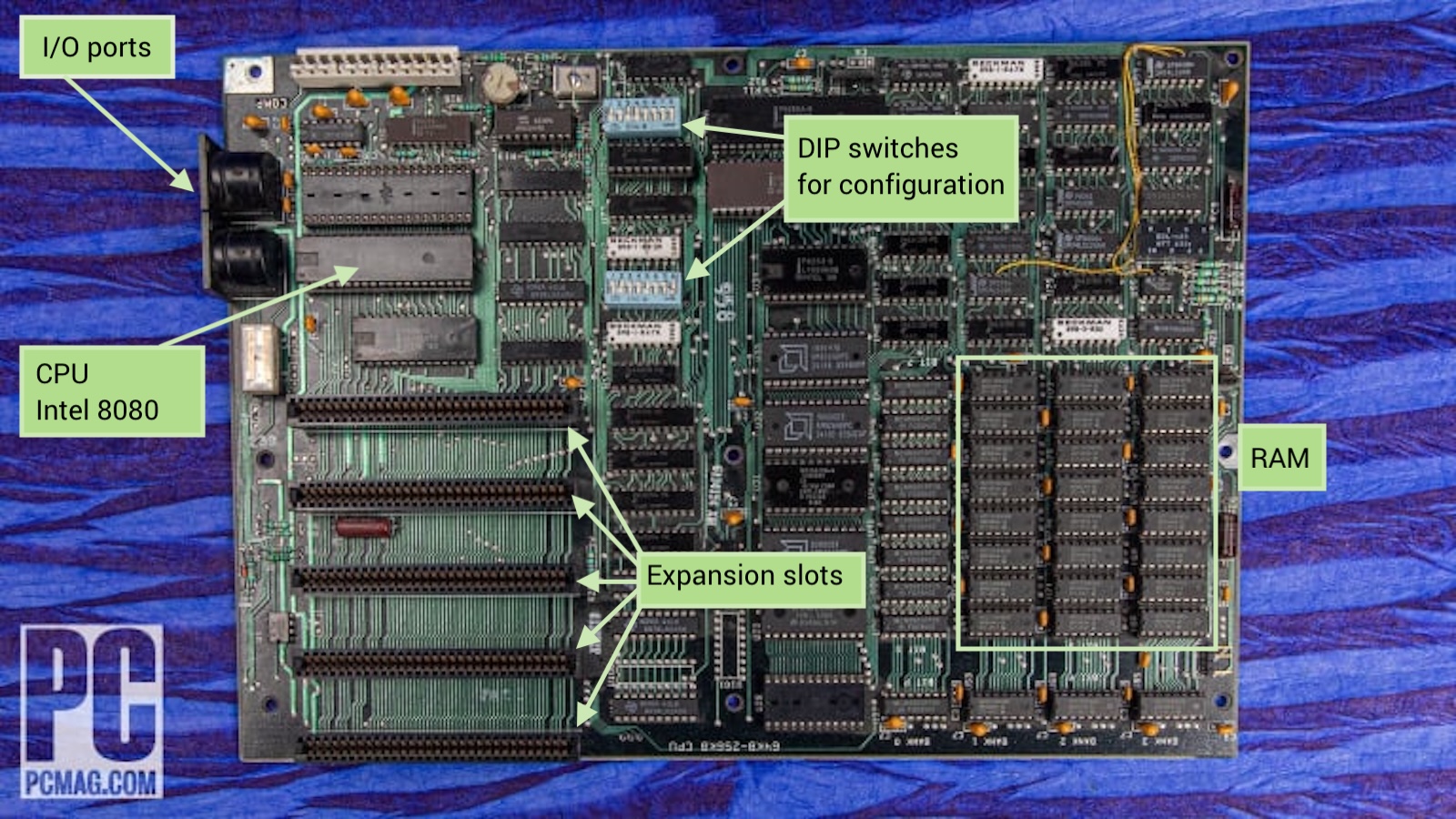

Here are some shots of a 1981 IBM PC, model 5150 (from PC Magazine1) with my annotations.

Despite the physical structure of this computer looking rather antiquated, the fundamental architecture isn’t that different from what von Neumann proposed, and is pretty similar to modern computers.

There’s a central processing unit—CPU—that fetches and executes instructions, that keeps track of what’s in memory, and that performs arithmetic computations.

There’s memory—in the case of the 5150 two floppy disk drives (which could hold up to 360 kilobytes) and some volatile memory on the motherboard.

There are connections for input devices—in the case of the original PC that was a keyboard (only).

There are connections for output devices—the external monitor.

If you wanted to be able to connect to a device like a printer, you’d need to add an expansion card with an extra port, but that doesn’t change the basics of organization.

Where we are today

To increase speed and reduce cost, more and more components came to be integrated on the motherboard. Moore’s law turned out to be a great predictor, and the number of transistors in integrated circuits increased dramatically. An Intel 8080 (what was used in the first IBM PC) had approximately 6,000 transistors with about 300 transistors per square millimeter.

Eventually, miniaturization technology and demand for more powerful and faster computers led to system-on-a-chip (SOC) designs. Rather than having memory and graphics units as separate elements on a printed circuit board, these were integrated on a single chip.

Where early PCs had a CPU with about 6,000 transistors, a modern Apple M3 SOC (2024) has over 100 billion transistors (depending on the number of cores).

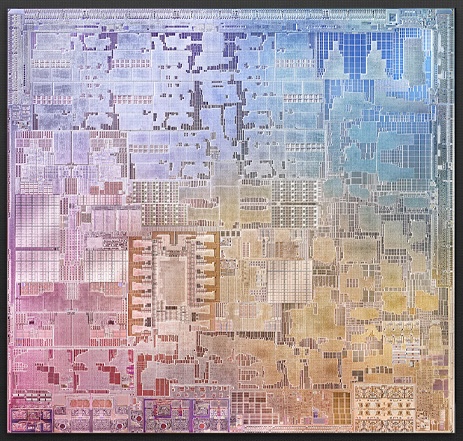

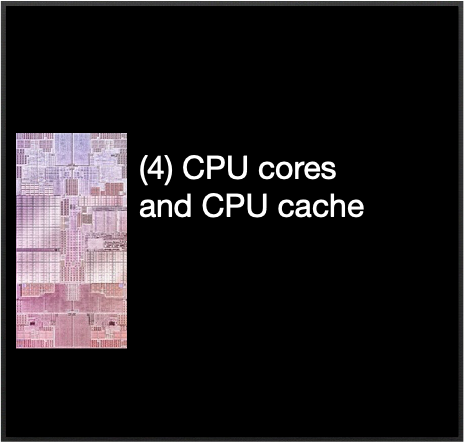

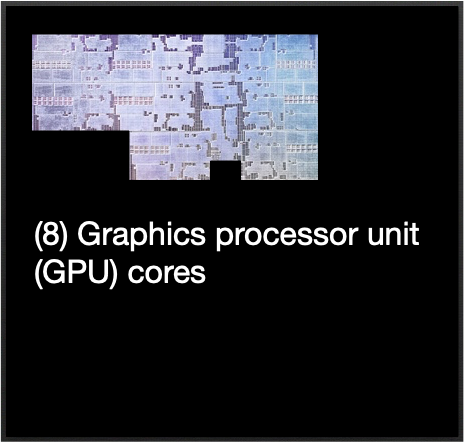

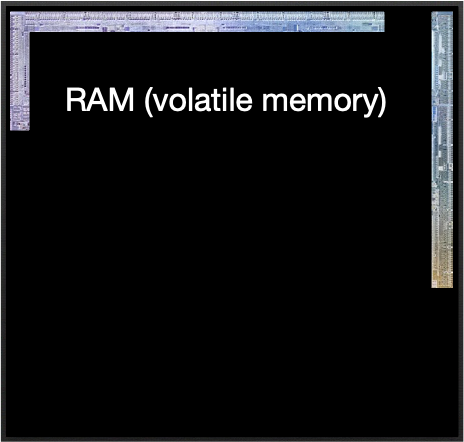

Here’s a die shot (photo) of an Apple M1 chip 2 from the Apple newsroom (with my annotations following).

This system-on-a-chip is approximately 120 square millimeters, roughly 11 millimeters on a side (about the size of your thumbnail, give or take), and has approximately 16 billion transistors. We’ll learn in detail more about the components that are included in this SOC, but the M1 includes:

- efficiency cores and performance cores (multiple CPUs),

- multilevel cache memory (L1, L2, SLC),

- main system memory,

- graphics processor units, and

- other components.

While this is a far more sophisticated design than anything von Neumann ever imagined, the basic design is the same—the CPU (or multiple cores) fetch instructions and data from memory, input devices write data to memory, output devices read data from memory, and control components orchestrate the interaction between components.

Of course, a modern laptop has far more input and output devices than the IBM 5150. For example, a laptop typically includes

- color LCD display,

- built-in keyboard,

- trackpad or other pointing device,

- camera,

- microphone,

- speakers,

- interfaces for additional external input or output devices (USB or Bluetooth), and

- wifi network adapter.

Phones and tablets include touchscreens, accelerometers and gyroscopes, and often multiple cameras.

So modern designs move as much as possible onto the system-on-a-chip (SOC) to increase speed, reduce size, manage energy consumption, reduce assembly costs, and so on. This kind of design was unimaginable when the first computer were made.

© 2025 Clayton Cafiero.

No generative AI was used in producing this material. This was written the old-fashioned way.