The relationship between Academy Award winning cinematographer Robert Richardson, who is a former UVM student, and Frank Manchel, professor emeritus of English and film, is seemingly not the stuff of a Hollywood screenplay. No embrace on the stage at graduation (there was no UVM graduation, in fact, for Richardson), no annual dinners to talk over the old days, yet the two have a late-blooming bond that has opened across time and distance.

Richardson, up for a third Academy Award Sunday evening for his work on Martin Scorsese’s Hugo, enrolled at UVM in 1973 and would spend a couple of years on campus before leaving for another school. While the university can’t claim him as a graduate, the transformation that set his path in life did take place here. It began with watching Ingmar Bergman’s The Seventh Seal at a film society screening on campus.

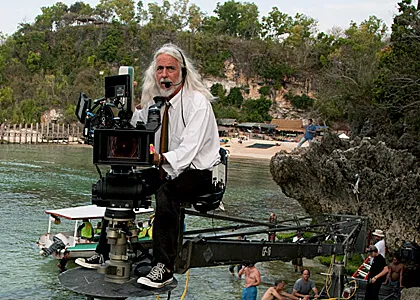

Richardson was transfixed, entering into a “zone” where everything beyond what was taking place on the screen fell away. “I think Bergman taught me how to look through an eyepiece,” Richardson recalls. “I think he taught me how to live inside of an eyepiece as if you are living in the zone. And I mean zone almost as akin to Jordan getting into the zone in basketball or anyone when they find that special place.”

Struck to the core by the legendary director’s artistry, the previously unfocused undergrad quickly beat a path to film courses, which led directly to Professor Frank Manchel’s classroom.

“Frank Manchel forced me into places I never would have walked and opened the door to extraordinary things,” Richardson told journalist Susan Green in an interview for the Burlington Free Press in 2004. “But he was very tough on me. His grading on my papers? Oh, Lordy! Even so, those classes were inspirational. He’s the most intelligent person I’ve met in the film world, in terms of teaching — as brilliant as Quentin Tarantino and Marty Scorsese.”

Sitting down for coffee in the Davis Center, basking in the glow of a late afternoon sun and the recent Super Bowl victory by his beloved New York Giants, Manchel laughs at Richardson’s memory. The retired professor recalls that when students would ask him about his reputation for being stingy with an A grade, he would say: “A+ is for God; A is for me; B+ is good enough for the rest of you.”

Richardson took all the classes he could with Manchel, though he admits he audited some to spare himself the lash of the professor’s red pen. A seminar on war films was among the courses in which he learned with Manchel; some twelve years later, Richardson’s breakthrough as a major motion picture cinematographer would come on a war film, Oliver Stone’s Salvador. The genre has been central to Richardson’s work, including Stone’s Platoon and Born on the Fourth of July, and Quentin Tarantino’s Inglorious Basterds, among others.

Richardson ultimately left UVM for a deeper education in hands-on filmmaking than the university could provide. He transferred to the Rhode Island School of Design for his undergraduate work and later earned a master of fine arts from the American Film Institute Conservatory.

Reel lives

Inspiring students to careers in film was familiar ground for Manchel during his long tenure on the UVM faculty. Among the most notable: screenwriter David Franzoni ’71, best-known for Gladiator and other sweeping historical dramas, and producer Jon Kilk ’78, who initially built his career through collaborations with director Spike Lee and has added names such as Julian Schnabel, Jim Jarmusch, Robert Altman, and Alejandro Gonzalez Inarritu to the list of leading directors he’s partnered with.

Kilik and Franzoni have largely remained close with Manchel through the years. Kilik makes near-annual visits back to Burlington to see Manchel, meet with UVM students, and often screen his latest project. (Look for details in March when the producer returns again to screen his new release, The Hunger Games.)

With Richardson, it was a different story. Manchel had no idea of his influence on the cinematographer until he read Green’s article in the Free Press some thirty years after Richardson had left UVM. But he and his former student would soon reconnect and have stayed in touch since with emails back and forth at least once a week, though they hadn’t met in person or talked on the phone over the past eight years.

That changed earlier this week when Richardson and Manchel talked film for seventy minutes on the phone, a wide-ranging conversation for a piece that will appear in a future issue of Vermont Quarterly magazine.

Calling the VQ office from a longtime family home base on Cape Cod Monday morning, Richardson spoke to the role the running e-dialogue with his old professor has had in his life. “I don’t have an ongoing email relationship with many people in the business. Frank is rather unusual for me,” Richardson says. “So the aspects of what I share with him are a wonderful balance between personal and professional. We can communicate about anything in the industry. This is a strong comfort zone.”

Richardson, Manchel says, writes in an elliptical style, almost like a haiku, unconcerned with niceties of punctuation or capitalization and with a distinctive cascading pattern to his line breaks, each line longer than the one before.

“He’s a kind person, insightful,” Manchel says. “He can take criticism and he turns it into humor.”

Their running email dialogue is usually about film, of course, often Richardson’s current and future projects. While his work has earned two Academy Awards, seven nominations, and the admiration of his former professor, it doesn’t mean that feisty professor is necessarily inclined to approve of all of his films.

Manchel had a deep disregard for Tarantino’s Inglorious Basterds and he let Richardson know it. The cinematographer tried to bring him around, sending positive reviews and the commentary of others. Though Manchel stands his ground, Richardson hasn’t given up on convincing him of the movie’s worth.

Manchel recounts their exchange about Eat, Pray, Love, an atypical Richardson project, which he took on out of a desire to do something different.

“He asked me what I thought,” Manchel says. “I wrote, ‘The opening shot was so beautiful… it’s a shame it couldn’t have been a documentary.’”

Richardson’s quick reply: “I get your point.”

No such worries with Hugo, a film beloved by Manchel and many, many others. The cinematographer will be up against stiff competition, particularly from The Artist and Tree of Life, when they open those award envelopes on Sunday. “I love this film,” Richardson says, adding what sounds a bit like a draft acceptance speech. “I’d love to be holding the Oscar for this film. Holding this Oscar for all of those who participated in Hugo.”

Richardson will be at the Kodak Theatre in Los Angeles on Sunday evening. Across the continent, there’s little doubt where Frank Manchel will be — less glamorous, maybe, but more comfortable, a seat on the couch in front of the TV with his fingers crossed for a student once lost, a friend later found.