On a frigid December morning in Burlington, Cynthia Herbert steers her SUV onto I-89 and settles in for the nearly 80-mile drive to Newport Center, Vt. It’s a long way to travel for lunch.

But each week, Herbert, a doctoral student in social, emotional, and inclusive education at the University of Vermont, and Nadiya Becoats, a UVM senior community health and wellbeing major, drive to the Newport Town School for its intergenerational meals program. The two UVM students co-facilitate the program alongside school staff and fill in where needed. They ferry salt and pepper shakers from the kitchen, set tables, empty trash bins, and collect data.

“One of the hallmarks of community schools is collaborative leadership where everybody takes ownership and accountability,” explains Herbert. “We come in and do what we need to do and fill in. … Because the last thing I want to do is walk into this community and look like a data miner.”

“We know that the hugs that we give the elders who are living alone are probably the only hugs they get that week." - Cynthia Herbert

The intergenerational meals program brings together area elders and elementary students to swap stories about secret fishing holes and video games, for example, over a family-style lunch and group activity. But the program does much more than put food in bellies. Interviews with participants have revealed the meals serve as a critical source of interaction.

“We know that the hugs that we give the elders who are living alone are probably the only hugs they get that week,” Herbert says. “Elders are saying how, ‘back in the Covid times a lot of us died and I think it's because we didn't have social contact—that it wasn't just Covid it was lack of social connection.’”

A recipe for community

Becoats and Herbert decorate tables with tablecloths and candlesticks while Michelle Robert—the school’s kitchen manager—puts final touches on the chicken curry casserole.

“Today is going to be tricky because the kids have never had this before,” she says. “I only put it out today because they are more apt to eat it because the elders are here.”

Robert strives to introduce students to healthy foods they may never have encountered before such as kiwi and purple cauliflower. The elders are a key ingredient in her success. They gently nudge children to try new dishes in the communal bowls.

“It’s a lot of fun to watch,” Robert says. “It’s a lot of hard work, but it’s worth it.”

She is part of a team of school staff committed to pulling off the meal each week. Because for them the lunch is so much more than calories in.

“It has brought back memories for me of my grandmother,” Robert says while elders start filtering in the gymnasium. “... This is also a great way for [the kids] to have conversations with people. I wonder what makes them come back. Is it the conversation? Is it the kids? I would love to know.”

For Peter Benson, a senior in the community, the meals are a highlight of his week. He started attending the lunches six months ago.

“My quality of life seems to be better,” Benson says during a holiday-themed Bingo game. “I don’t seem to be as depressed. I have more fun with these kids than any friends. They are so smart.”

He scans the room with a smile.

“The world is going to change, and these kids are going to be the ones that will change it for the better,” he says.

As if on cue, a second grader to his right notices that Benson missed one of the calls and quietly slides a chip onto his Bingo card. Across the room, a little girl rests her head on the shoulder of Linda Waterman, a retired substitute teacher credited with enlisting most the seniors in the room.

The benefits of the meal program go both ways. Parents have reported it has improved their children’s speech and language development and helped their kids become leaders in the classroom, Herbert says.

“I’ve seen the elders provide that active listening that a lot of times we as parents are moving so fast you forget to stop and listen to these kids,” Herbert says. “They are able to attend to kids; it’s like those little drops in a bucket. You just never know what they’re going to grow.”

A blueprint for success

As meal service winds down data collection begins. Shelly Lanou, the school principal, scrapes uneaten baby carrots, green beans, and chicken curry from plates into a plastic bucket for Becoats to measure food waste.

Preliminary findings suggest waste is significantly less in the intergenerational meal program than when children eat with their peers, she says. In the control group, social dynamics influence food consumption as students watch as their friends eat—or don’t—a particular item. The slight shake of a head can make a difference.

“They aren’t going to be the one kid that indulges even if they might like it,” Becoats says.

At each luncheon, the researchers collect surveys from elders to measure satisfaction of the event as well as risk factors for social isolation. Some of the best evidence that the program is working may be even more simple—the elders keep coming back. The lunches are expanding to new locations, too.

This spring, more schools in the supervisory union will launch intergenerational meal programs using a blueprint UVM researchers and Newport Town School staff compiled.

“We are trying to create a toolkit, so they don’t have to learn everything the hard way,” explains Lanou. “It’s not scripted because at the end there is fluidity to this. It’s what works in your community and meets your community’s needs but there are definitely some tenets we have learned that have to be included: The family style meal is the linchpin.”

Newport Center’s meal program was born, in part, from necessity. Before the pandemic, volunteers ran a weekly meal service for area elders, but it folded during Covid. Shelly Lanou noticed area seniors were becoming more isolated and that students needed more opportunities to develop their social emotional learning skills.

Her solution was lunch. There is a reason the former U.S. Surgeon General called for Americans to break bread together: it’s good for us. Eating in community is good for our bodies, our souls, and the fabric of society.

Since the school already had staff who could prepare meals at scale, Lanou wondered if an intergenerational meals program could meet both the needs of local children and elders. Moreover, deepening ties between residents and the school is central to being a community school.

“A mindset shift”

In 2021, Vermont legislators passed Act 67 to pilot and assess the community school model in rural communities. Newport Town School is one of five original sites awarded funding to join UVM’s Catamount Community Schools Collaborative, a partnership of UVM, the state’s Agency of Education, and Vermont public schools. Community schools reimagine the role of school. They are vital connective tissue in a region, bringing together resources and services to improve outcomes for students and the broader community.

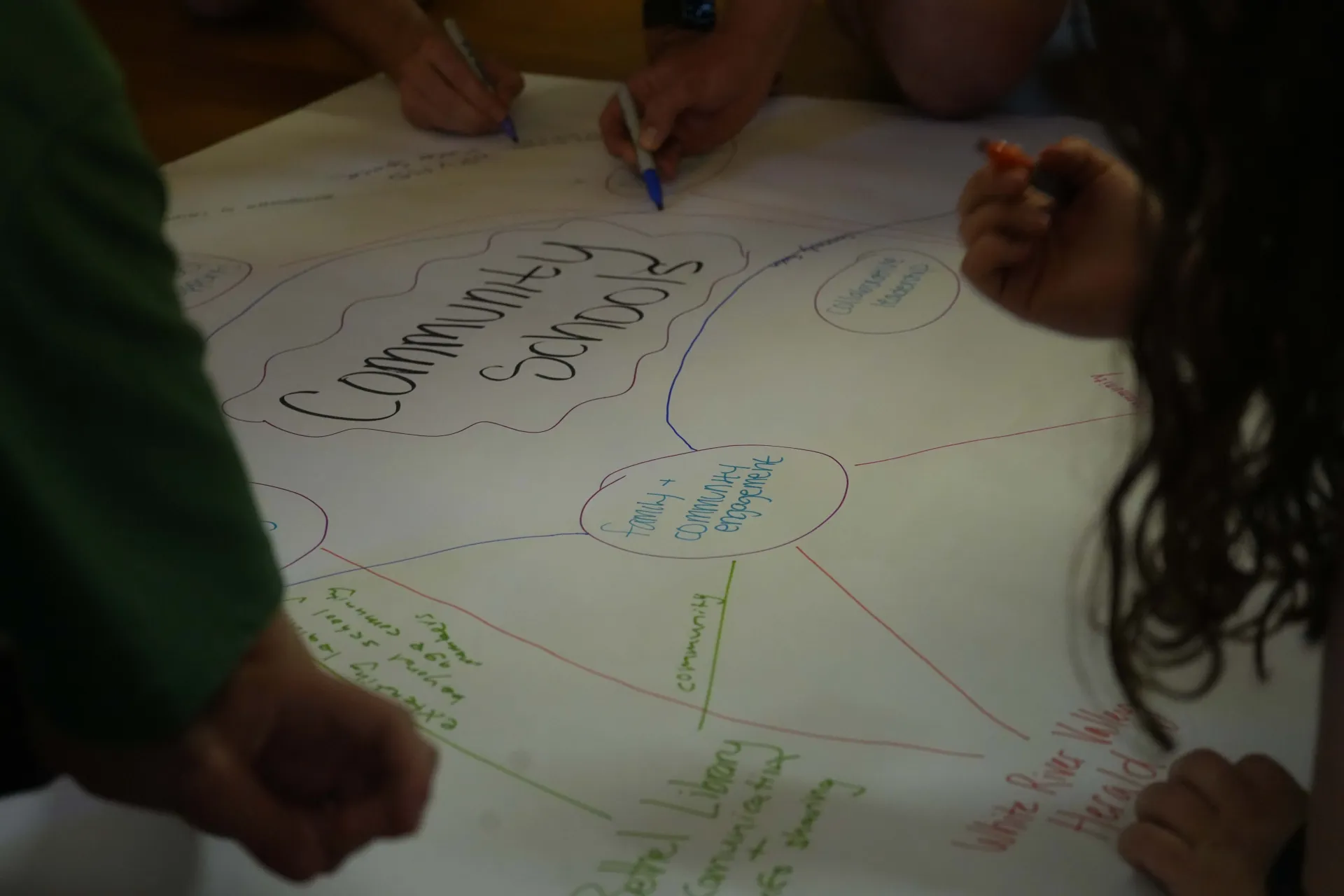

But there is no one way to be a community school—just a framework of five pillars outlined in Act 67, including integrated student support, expanded enrichment activities, active family and community engagement, collaborative leadership practices, and safe, equitable, and inclusive learning environments. This allows schools to develop individualized plans according to their needs.

For instance, Newport Center’s intergenerational meals program was devised to overcome a community challenge. The Catamount Community Schools Collaborative was awarded a grant from UVM’s Leahy Institute for Rural Partnerships to help address it. They partnered with the Newport Town School to implement and research the intergenerational meals program. The funds help cover the cost of meals for the seniors and to refine the program using data.

“Without the partnership could we do meals here?” Lanou asks. “Probably. Could we come up with activities? Probably. But could we have the data that shows the difference this is making in people's lives? Would I be doing surveys every week? Would we have these amazing quotes from these elders about how they felt invisible in society and they feel belonging here? None of that part would happen without the collaboration, the connection that commitment from UVM.”

The partnership also prevented them from giving up on the program.

“There were moments where it was overwhelming,” Lanou admits. “You learn as you go. And things get more efficient. They get more effective. But in the middle, there's a lot of disruption.”

But it was worth the initial stress when staff saw what everyone gained at the lunches.

“It’s just about the mindset shift,” Lanou says. “… On a day-to-day basis we are responsible for each other and not just to survive but to thrive.”

An old/new way of doing school

Some scholars trace the idea of community schools back to the philosopher and educator John Dewey, who believed that schools were a cornerstone of society and a hub for community. But modern community schools typically exist in urban areas where there are more services to lean on. That’s why Vermont’s experiment with rural schools is unique. And it requires thinking differently about what partnership looks like.

“Children who aren't fed, supported, engaged, or feel safe can't learn,” says Bernice Garnett, UVM’s Adam and Abigail Burack Green and Gold Associate Professor of Education and the principal investigator studying Act 67’s implementation. “But often that requires partnerships, expertise, and resources that might be beyond the folks in the school walls or in the school’s budget.”

Community schools expand the circle of help.

Garnett points to Newport Center’s intergenerational meals program as an example of the university-assisted community school model in action, where universities serve as long-term partners with community schools to offer financial support, human capital, and expertise, she explains.

It’s a model and she knows well. Garnett experienced it as an undergraduate at the University of Pennsylvania’s Netter Center for Community Partnerships where it was pioneered. The Catamount Community Schools Collaborative aligns with the university-assisted model, and UVM scholars are heavily involved in the national network of community schools, Garnett explains.

In Vermont, each community school has a different approach for addressing the needs of the community. For instance, some offer space on their campuses for school-based health centers that provide medical care for students, staff, and their families. Other schools broaden their definition of a community partner.

In Cabot, Vt., middle school students were trained to provide afterschool care for younger kids alongside an adult volunteer, Garnett says. “The term community partner may be your neighbor who knows how to track prints in the snow, who doesn't have an LLC, or a building, or a fancy website, but is a partner because he's coming to school to provide services and content.”

Some Vermont community schools have re-examined uses for their buildings. In Vergennes, the school is open almost every day of the year to the community because it also serves as a recreation center. This may also give people in town a greater stake in the school’s future.

Are community schools working?

For the past four years, Garnett and Peter Knox, an assistant research professor at UVM, have assessed the community school model in Vermont, interviewing administrators and compiling evidence that the approach is working. But measuring the impact involves data—and time.

Garnett explains that this type of change typically requires at least five years to produce socially significant outcomes, such as increased attendance and graduation rates, higher academic achievements, and decreased mental health referrals.

“In almost every way you can think of Vermont is uniquely positioned to have this be the way our state does school. - Peter Knox

But state funding for the pilot only lasted three years, before receiving a one-year extension. In 2024, Garnett was awarded a $300,000 grant from the Leahy Institute for Rural Partnerships to continue data collection and to fund internships for UVM students in community schools. That funding, along with another infusion from the state, and a three-year congressional direct-spending grant secured by Senator Bernie Sanders enabled the pilot to continue and expand into more communities in 2025.

“People want pretty quick results,” says Knox. “They want to know are math scores going up or what do the [English Language Arts] scores look like?”

But shifting school climates and building a culture of engagement requires patience. Still, the early evidence is encouraging: chronic absence in community schools is falling, the networks of organizations partnering with schools are expanding, teacher turnover rates are declining, and several districts have invested in permanent community school coordinator positions.

“We have a lot of preliminary evidence that lends itself to us thinking this model is working,” Knox says. “But really we're going to understand the true impact of this 5,6,10 years down the road when we can start talking to students who have gone through a Community School or went through a Community School district.”

Knox believes most Vermont schools are already operating like a community school—they just lack the formal framework for streamlining resources and engaging partners. Because relationships are the heart of community schools.

“In almost every way you can think of Vermont is uniquely positioned to have this be the way our state does school,” he says. “And we I think have the ability to be. We're small enough and nimble enough that we can make it happen here.”

Vermont’s small size is its strength.

Building community resilience

Jason Di Guilio, the principal of Hazen Union School in Hardwick, walks through the halls greeting students by name. He tours the new wellness space for students who need a few minutes to regroup before ducking inside a shop class where students are working in teams. But things at Hazen weren’t always this calm.

Di Guilio recalls the chaotic years of Covid.

There was a lot of yelling, he says. Parents yelled about people wearing or not wearing masks, and students got into physical altercations with each other. Bullying increased.

At Hazen, there was a lot that was broken and needed fixing.

“There was a lot of fear, and I think it manifested as behavior and attendance and anxiety,” Di Guilio explains. “That first year or two, it was nonstop in this building from 7 in the morning to 3 in the afternoon, just nonstop action. Interceding. Providing intervention. Providing space. Dealing with behavior. Dealing with tears.”

Several teachers left and replacing them proved difficult. Rebuilding Hazen after Covid required thinking differently. Teachers and administrators had to reckon with the fact that some students come to school not ready to learn because of factors like homelessness, food insecurity, fear of bullying, or challenges at home.

“And very few of those [factors] the school has any control over at all, but we are still responsible,” Di Guilio says. “… I am under no illusion that we can fix homelessness, but we are burdened by it. Our families experience it.”

But what we can do is leverage our connections and space to bring people to the table that can help in that situation, he continues. “That is what community schooling is all about.”

A big part of shifting to a community school model began with changing his own mind. As a teacher, Di Guilio didn’t think it was his job to deal with external factors affecting students. Covid forced him to change.

“We saw what happens when school shuts down,” he says. “People don’t eat. They don’t have access to mental health. And their social-emotional and academic needs aren’t being met. We saw that. That is the reality. So, the stoic in me says I have to embrace reality. And the stoic in me also says that I have to understand that I don’t have the skills nor the resources to deal with that level of problem.”

That’s where community partners can alleviate some of the burden.

The cultural shift at Hazen began in 2021 when the school joined the community school pilot project and began mapping the community’s assets to identify gaps and create programming to close them. Hazen administrators also devised a set of behavioral expectations for students, staff, and community members so that everybody feels welcome inside.

“There is a cost to entry,” Di Guilio says. “… It means is we don’t scream at each other. We don’t swear at each other. We don’t push each other. … We found that we have to teach people how to disagree.’”

Over the past four years, the school created a bike tech maintenance program, launched its most popular course—Recipe for Human Connection—with Vermont’s Center for an Agricultural Economy and began collaborating with local trail networks. After flooding destroyed Hardwick’s community gardens, they were replanted on school grounds outside the flood zone. The school now hosts the town’s farmer’s market over the winter and opened a school-based healthcare clinic so that students could receive care on site. This is a community school in action.

“I believe Hardwick is more flood resilient because of community schools,” Di Guilio says. “But that is a belief I can’t prove. I think our relationships are tighter.”

Strengthening relationships

There are benefits he can prove. Like the significant decrease in chronic absenteeism, particularly among ninth graders, where absences have been reduced by half.

“Here is some raw data,” says Di Guilio, sliding a sheet of paper across the table.

“In 2021, there were 609 total absences, and then there was 1,000,” he points. “So, we saw a spike in there and then we saw a strong recovery. And what we tried to do was look at individual relationships with kids.”

A student is more likely to return if someone they trust reaches out, he explains.

The school also hired a part-time driver to pick up kids who need a ride. The goal was to remove barriers—psychological and physical—that prevent students from coming to school. Di Guilio credits the cumulative power of these efforts for making a difference.

“Once we started nibbling away at the edges it became very clear who the most needy kids were,” he says. “It’s not perfect yet. We’ve reduced [absenteeism], but we haven’t conquered it.”

There are also positive changes for Hazen faculty and staff. Teacher turnover at Hazen is nonexistent. And in 2025, Di Guilio was named Vermont’s Principal of the Year.

“I haven’t lost anyone because they don’t feel supported,” he says.

Back in Newport Center, the UVM research team folds tablecloths and collects surveys after the intergenerational lunch. They hug elders before they leave and the space is transformed back into a gymnasium.

The meal has become an important ritual in their lives. Nadiya Becoats and Cynthia Herbert travel to the Newport Town School year-round to assess the program’s impact. They come after snowstorms. They come during the summer. And people notice when they aren’t there.

“It’s going to be sad to leave this place,” Becoats says. “College is such a bubble with age. I missed that familial feeling of many generations in a room.”

Herbert nods in agreement.

“I think everyone needed each other in different ways—even the researchers.”