| |

Slow Beginnings

St. George is the smallest town of Chittenden County and all of Vermont, surrounded by Williston to the north and east, Hinesburg to the south, and Shelburne to the west. 1 The governor of New Hampshire, Governor Benning Wentworth issued a charter on August 18, 1763 dictating that St. George would be 23,040 acres. However, due to previous land constraints by the surrounding towns, the actual acreage of St. George ended up encompassing fewer than 2,500 acres even after gaining a small piece of land from Shelburne in 1848. 2 Compared to neighboring Williston that is better suited for various types of agriculture, St. George possesses no significant waterways and is encompassed in valleys and hills.3 Moreover, the soil only successfully yields certain types of agriculture, including local grains and fruits. By 1791, St. George had almost sixty inhabitants including the Ishams, descendants of St. George’s first settler, Joshua Isham, the Lockwoods, and the Suttons.

Life and agriculture in St. George started off slowly compared to other towns in the southern portion of Chittenden County. St. George’s first inhabitant, Joshua Isham moved to the area in 1784 and created a rudimentary construction and worked on his primitive farm for nine years before others moved into the region. 4 Although the surface of St. George was uneven, the soil was generally good and “well adapted for cultivation, though the inhabitants directed their attention chiefly to dairying.”5 In the first half of the nineteenth century, farming in St. George appeared to be subsistence farming alone, due to the residents inaccessibility to major points for trade, or significant waterways for convenient travel. However, a handful of families emerged in this tiny town and established themselves for the long-term.

Minimal Growth

According to the U.S. Agricultural Census in 1870 and 1880, inhabitants were able to expand their holdings, yet production slowly grew or in most cases, dropped. 6 For instance, Nathaniel Lockwood possessed thirty four sheep in 1870, but ten years later, he only possessed twenty. This trend among many other St. George inhabitants shows the eventual decline of the Merino sheep population, a breed popular to Vermont in the nineteenth century. On the other hand, farmers including Patrick Filbon, Edward Isham, and Norman Isham all increased their dairy cow population, a clear indication of the rising dairy farm production to make up for the declining sheep trade. 7 These trends are at a very small scale compared to the rest of Chittenden County, but they show a precise example of how farming in St. George did not grow in large quantities, but rather stayed to accommodate the needs of the residents.

Among the crops grown in St. George, corn and oats appear to be the largest commodity grown among the scattering of farmers throughout the valley. Although the number of bushels of corn remained roughly the same between 1870 and 1880, the production of oats did drop somewhat. Another trend that emerges is the small rise of barley. In 1870, John Davis and Linus Isham each grew forty and seventy bushels of barley respectively while in 1880, Edward and Norman Isham, Henry Lawrence, Rollin Forbes, and Orrin Turrill each possessed their own barley crops ranging from 14 - 300 bushels.

Although the residents in St. George did not produce much agriculturally, most of their land holdings were extremely vast and wide-spread. Nathaniel Lockwood in 1880 owned 200 acres of land worth almost $10,000, a large amount of money for his land in which only 50 acres was unusable.8 Moreover, Goose Creek Farm near the St. George-Williston town line is over 100 acres, a very large percentage of the total composition of the petite town. Another tiny trend that seemed to emerge was sharing farm space due to the lack of available holdings. Hiram Isham and Ira Bromley worked on Isham’s farm on halves in which they shared the expenses and the profits. Together these two worked with “7 cows, 2 heifers, 16 hens, 1 rooster, 3 hen turkeys, 1 gobbler, 1 roan horse named Tom.”9 One interesting commodity that one farmer managed was bee keeping. Rollin Forbes (shown below) owned a honey business in which he housed multiple bee hives to produce honey. In his diary he documents his success:

“the season is over and the honey all sold. I got 2,200 one-pound sections filled and about 200 pounds of extracted honey. I begun the season with 45 colonies, rather week. I had 22 natural swarms and one that came to me and one that I took out of a tree and put thim in a hive all ready for housekeeping. I got 65 lbs. of nice white honey out of the tree, gathered this season, and have 69 colonies in the cellar with sealed covers. I raised the back end of the hive up a little that gives thim plenty of ventilation and a good chance to keep the (entrance) clean. the rest are out side in mannour hives packed with planed shavins and sawdust mixed. I make all of my hives and crates. I made some 10 frame hives but I think the 8 frame hive is large enough for my locality if they have plenty of surplus room and by raising the hive a little from the bottom board I am not bothered much with swarming. Today Jan 3rd bees are having a good fly, the only times since november 27.” 10

The Forbes’ honey business lasted until Forbes’ death, and his son (also pictured) did not continue the production. Since honey production was by no means a lucrative crop, Forbes also grew apples, potatoes, and onions which he peddled in Burlington.

Figure One: Picture of Rollin Forbes and his son in front of the bee houses. (From Look Around Chittenden County Vermont)

Nominal Agricultural Future?

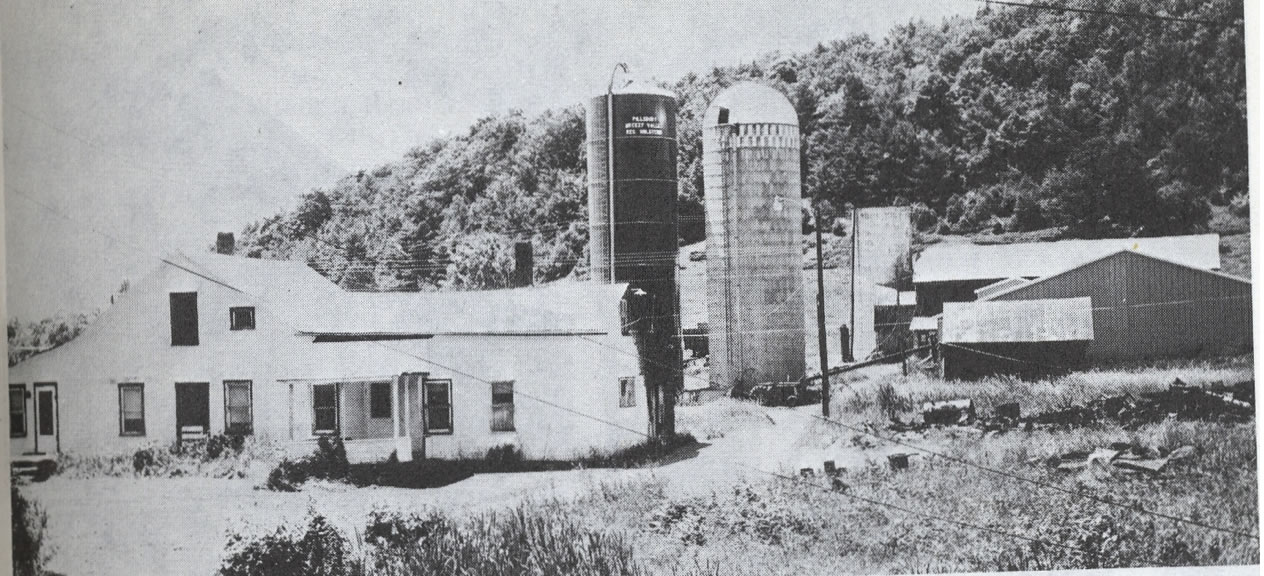

Trends in the twentieth century did not change much in St. George. In the 1960s, St. George was able to boast being the fastest growing town in Vermont due to its increased size from 108 to 477, however its agricultural status could not boast the same. 11 There is only one operating farm remaining in the town presently; Pillsbury Farm utilizes 170 holstein cattle, include 100 dairy cows on 200 acres of land. Due to its small size and lack of substantial growth to actually form a cohesive town, St. George remains completely rural, and agriculturally slim.

Figure Two: Pillsbury Farm. (From Look Around Chittenden County Vermont)

***

1. Lilian Baker Carlisle, ed., Look Around Chittenden County Vermont (VT: Chittenden County Historical Society, 1976), 323.

2. Hamilton Child, Gazetteer and Business Directory of Chittenden County, Vermont: 1882-1883 (Syracuse NY: Hamilton Childs, 1883), 256.

5. Look Around Chittenden County Vermont, 312.

7. US Bureau of Census. Productions of Agricultural in the Town of St. George, Chittenden County, Vermont. 1870, 1880.

8. Look Around Chittenden County Vermont, 341.

10. Hamilton Child, Gazetteer and Business Directory of Chittenden County, Vermont: 1882-1883 (Syracuse NY: Hamilton Childs, 1883), 256.

11. Look Around Chittenden County Vermont, 341.

|