History

Maps

Photos

Resources Home |

Agricultural History of Huntington, Vermont

prepared by Sebastian Renfield 2009

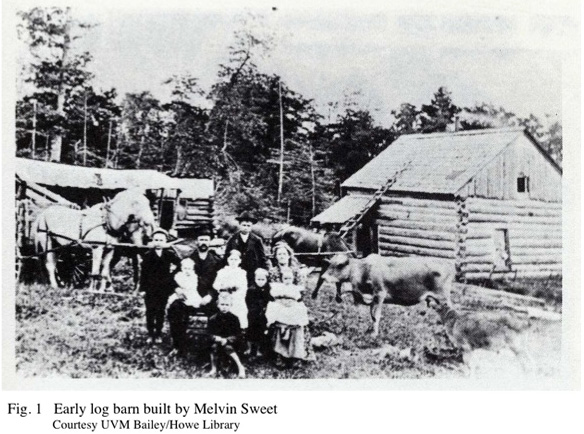

Situated in a narrow valley along the Huntington

River, the town of Huntington was chartered in 1763, but not settled

for more than two decades afterward. The earliest inhabitants of

European descent moved north from Bennington County, Jehiel Johns of

Manchester being the first in 1786, followed a year later by Ebenezer

Ambler and Charles Brewster, both of Tinmouth. These first

settlers immediately set about the task of clearing land, using the

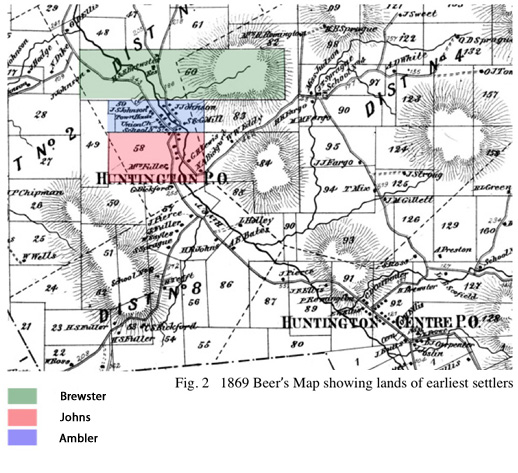

logs to build their homes and barns (Fig. 1), and settled three lots in

what is now the village of Huntington, Johns on lot #58, with Brewster

and Ambler on #60 and #59 respectively (Fig. 2). These log

structures have vanished, but in a small self-published volume, early

chronicler James Johns (son of Jehiel Johns) lists the earliest frame

buildings built in the various portions of the town. The first

were a house and barn built for Charles Brewster in 1795, and at the

time of Johns’ account in 1861, his original barn was still standing,

though it is no longer extant. The following year, a barn was

built for Ebenezer Ambler. In 1821, this structure was moved a

hundred yards south, and was used as an outbuilding of the Green

Mountain Hotel in the lower village before being taken down in the

early 1860s.1 In the eastern part of the town, the

first barn was built for John Martin around 1800, and by 1864 had been

placed on a new foundation. Jacob Snider was the first settler

along what is now the Hinesburg Hollow Rd., and his original farmstead

at 925 Hinesburg Hollow Rd. was later sold to the Bickford family, who

owned and operated it throughout much of the 19th century. The

rear portion of the farmhouse currently on the property is thought to

be Snider’s original house, erected around 1800.2

Compared to what could be found in nearby areas like Richmond or

Hinesburg, Huntington had a limited amount of flat valley farmland. Though the town would always be rural in character, it was never destined to be an agricultural

powerhouse. Huntington's

population remained less than a thousand for two hundred years after

its founding, though even into the 1940s, over half of the population

lived on working farms.3 With its hills and mountains,

various 19th century gazetteers made it out to be rather inhospitable.

As John Calvin Smith’s 1840 gazetteer put it, “The surface is very

uneven lying on the Green mountains and containing Camel’s Rump [sic.]

one of its highest peaks in its part. Watered by Huntington River, a

branch of Onion River, which affords water power. The soil is sterile.”4

This was a common theme, and following what he considered to be a

particularly unfavorable review of the town in Thompson’s gazetteer,

James Johns included a more optimistic description in a revised version

of his history of the town, in which he states, “The surface of the

town is mostly hilly and mountainous, excepting the tract of interval

lying on the river. Most of this hill land, not immediately on the

steep mountains, is under good cultivation, and bears good grass,

grain, and Indian corn, and affords besides (when not too rocky),

excellent pasture for cattle.”5

Throughout the nineteenth century, oats, corn,

wheat, and hay were the principle crops, and potatoes, lumber, maple

sugar, butter and cheese were also produced. According to

the 1880 census, an average Huntington farm in that year had only an

acre or two of corn, an acre of wheat, perhaps two acres of oats, and

an acre of potatoes. The majority of tilled land was used for the

cultivation of hay. A typical farmer might have thirty to fifty

acres of hay, each acre producing approximately one ton of cut

hay. A larger farm might have over a hundred acres, and even a

tradesman who did not depend on agriculture for his living might have a

few acres of hay, enough to support a horse or two. On average, farmers

in 1880 had an acre or two of apple orchard, cut 30 or 40 cords from

their wood-lots, sold $10 worth of produce, and most had sugaring

operations that produced four or five hundred pounds of maple

sugar. A few farms with larger sugarbushes produced double

or triple that amount, but no maple syrup production was

recorded. Each dairy cow yielded about a hundred pounds of butter

annually, and a farmer with two dozen head of dairy cows could expect

to produce five thousand pounds of cheese in a year.

In light of the town’s geographic limitations,

Huntington’s hillsides would have been a logical place to pasture sheep

when the merino breed was introduced in early 1800s. In 1840,

there were 4,721 sheep in the town. Sheep

outnumbered cows, but large-scale sheep operations vanished rapidly in

the following decade. By the time of the 1850 census, though

sheep still outnumber cows

nearly two to one, only 1,500 were counted. Three farmers in the

entire town had flocks

that numbered over one hundred, those being Jeremiah Remington, Henry

Ross, and Amos Gorton. Only two-thirds of the farms listed had

any sheep at all, and most of those had between two and ten sheep. Interestingly,

1840 was also the year that the human population peaked at 914

residents before declining steadily for the next 130 years.

In his firsthand account, James Johns freely admits

that it took “nearly 40 years before any part of it began to assume the

appearance of a village and place of business,”6 but between

sheep and timber, the middle of the 19th century brought relative

prosperity to Huntington for the first time. The Forest Mills

Lumber Company established its operations on the western slope of the

Green Mountains just below the Camel’s Hump, and by the 1880s, six

sawmills were operating. After 1840,

sheep rapidly lost ground as the dominant type of livestock, although

their numbers rebounded briefly from 1860 to 1870, doubtless in

response to the increased demand for wool due to the Civil War.

Unlike their fellows in other parts of Vermont, the farmers of

Huntington showed little interest in continuing to breed sheep at all,

and by the outbreak of the first World War, sheep were virtually absent

from the town, with numbers in the single digits rather than the 1,500

present six decades prior.

Livestock trends followed the typical Vermont

pattern of declining numbers of sheep and increasing numbers of dairy

cattle (Fig. 4), as wool prices continued to fall and improvements in

transportation made larger-scale dairying more profitable, as butter

could be shipped further. By 1880, cows outnumbered sheep two to

one, their ratio neatly reversed in the span of thirty years. The

census shows only a handful of farmers with herds numbering greater

than thirty head of dairy cows. Roughly one third had more than

fifteen, and many had only a few, but the overall number of cows

continued to rise gradually (although the human population was already

declining) until after World War Two. Although the 1880 census

showed no milk products being sold to creameries, by 1899, Huntington

had three creameries operating, G.M. Norton’s, the Green Mountain

Creamery, and the Hanksville Co-operative Creamery.7

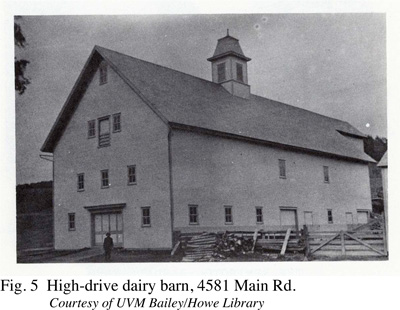

The English barns of the earlier part of the nineteenth century were

gradually replaced by larger and more complex structures, culminating with

the massive high-drive dairy barn of the turn of the century, a fine

example of which is still visible today, at Jubilee Farm on Main Rd.

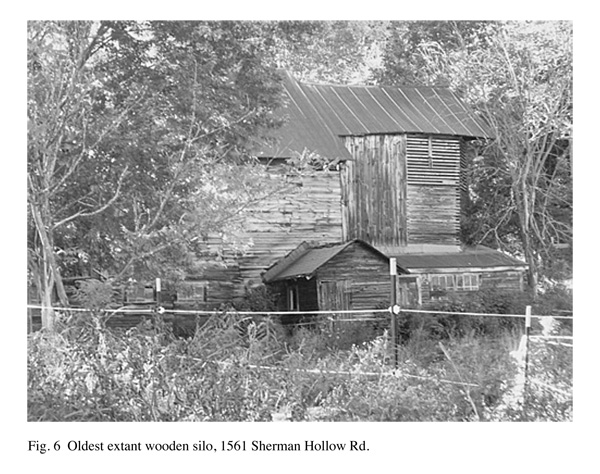

(Fig. 5). As dairying technologies advanced, silos were developed

as a more efficient means of storing winter fodder. The oldest

silo still standing in Huntington is located at 1561 Sherman Hollow

Road (Fig. 6). Representative of an early type of wooden silo,

it is constructed of stacked two-by-fours, and dates to about

1890. In 1928, there were 39 silos in town,8 but today the Sherman Hollow Rd. silo is one of a mere five. Though there were others of this type present

into the 1940s, it is the only

remaining wooden one.

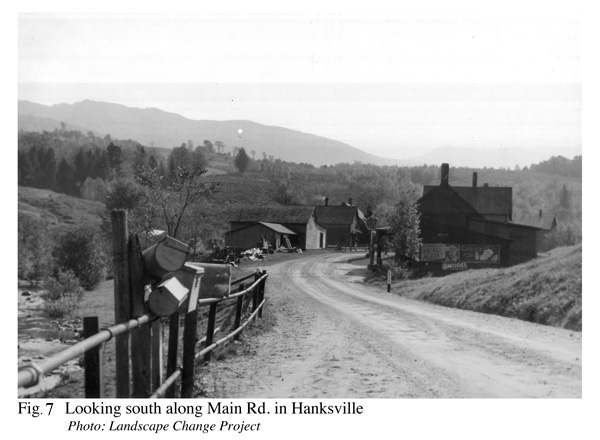

The 1945 agricultural census data provides a

snapshot of farming at a time of great change across the nation.

At that point, the number of working farms was two-thirds of what it

had been fifty years prior, and at eighteen dollars per acre, the land

values were the lowest in Chittenden County, second only to the

virtually unpopulated district of Buel’s Gore. Although three

quarters of Huntington’s farms had running water, only half had

electricity, and only eighteen percent had tractors. The numbers

of dairy cattle were half of what they had been a mere decade

earlier. Lower hillsides were still bare of timber, as

shown in a photograph looking south along the main road in Hanksville

(Fig. 7) , but upper slopes were tree-covered, as the timber boom had

ended. Late 19th century photographs show the beginnings of

intentional plantings, and by the 1930s both natural and manmade

reforestation was well underway, as farming declined and less

pastureland was required. , but upper slopes were tree-covered, as the timber boom had

ended. Late 19th century photographs show the beginnings of

intentional plantings, and by the 1930s both natural and manmade

reforestation was well underway, as farming declined and less

pastureland was required.

Huntington’s population had reached its historic

peak in 1840, and for the next 130 years, it declined steadily (Fig. 8). By the 1960s, a number of barns had fallen into disuse

and disrepair. Among the notable losses is the barn on the

Noah Johnson property, located in Huntington village, a hand-hewn

timber-framed structure built in the early 1800s, standing for 150

years before falling victim to arson in 1975.9 A barn

built by Alfred E. Bates, complete with gothic revival cupola,

once stood on Main St. near Rocque Drive and is now gone. As late

as 1979, the Buttles farm, located at 5340 Main, just south of

Huntington Centre, had a large barn dating from 1850, with several

smaller additions in the later 1800s. At this time,

only the two smaller structures attached on the right are still

present.

Beginning in 1970, a rapid influx of new residents

more than tripled the population in a few decades. At the time of

the 2007 census, Huntington had thirty-two working farms, a number of

which operate on the Community Supported Agriculture model, growing

vegetables and raising sheep, pigs, chickens and cows. In spite

of the renewed cultural interest in local agriculture, many of the

town’s hilltop farmsteads are abandoned, forests have returned, and

most of the old barns are used for storage if at all.

(Back to Main Page)

1 James Johns, A Brief Sketch or Outline of the History of Huntington (Huntington, Vermont: Self-Published, 1861)

2 Vermont Historic Sites and Structures Survey:

Chittenden County (Montpelier Vermont: Vermont Division for Historic

Preservation, 1979)

3 Farm Census for the Towns of Chittenden County, Vermont (Burlington, VT: UVM Cooperative Agricultural Extension Service, 1946)

4 Daniel Haskel and John Calvin Smith, A

Complete Descriptive and Statistical Gazetteer of the United States of

America (Sherman & Smith, 1843)

5 Hemenway, A.M., ed. The Vermont Historical Gazetteer Burlington, VT: 1868-91. 813

6 James Johns, A Brief Sketch or Outline of the History of Huntington (Huntington, Vermont: Self-Published, 1861)

7 1898 Vermont Agricultural Report (Vermont State Board of Agriculture, 1899)

8 1928 Vermont Agricultural Report (Vermont State Board of Agriculture, 1930)

9 Hallock, Olga M. ed. Huntington 1786-1976 (Huntington VT, 1976)

|