|

||

| uvm a - z | directory | search |

|

DEPARTMENTS LINKS

|

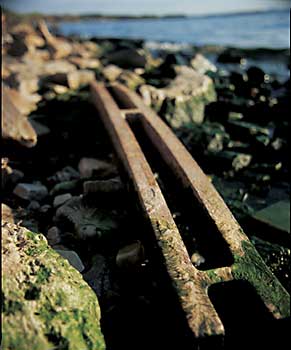

photo by Andy Duback

Marginalia

Notes on a remembered waterfront

by

Maria Hummel ’94

When I was six, I learned to swim in Lake Champlain by walking out until

I stood chest deep, closing my eyes, and diving toward shore, kicking

hard until my belly scraped bottom. At eight I skated out onto Burlington

Bay and saw my first black ice, deep dark galaxies that extend from the

January shorelines around the Queen City. At nine I found a thick oak

staff on the beach, and trapped in a Tolkien phase, burned magical inscriptions

into it. At thirteen, now living 20 miles inland, I drank my first illicit

beer on the cliffs of Red Rocks Park. Soon after my sixteenth birthday,

my friends and I came upon a castle of ice in Oakledge Cove, a glassy

confection thrust up by a sudden winter storm. We gamely climbed all over

it, nearly sliding to our deaths in our cheap shoes.

Born in 1973 and raised in the Irish-French neighborhoods of the South

End, I grew up with a waterfront very different than the greened-up expanse

people know today. It was a mysterious borderland, watched over in the

north by Battery Park with its smell of French fries from Beansie’s

school bus, and in the south by the great round oil tanks and the old

barge canal, a coal-slag Superfund sight shrouded by trees. When I was

a kid, people went straight to the beaches, but didn’t traverse the

in-between. For most, the Burlington waterfront was a series of destinations

instead of journeys. But not for my brothers and me.

According to the Burlington Waterfront Revitalization Plan, in 1990 there

were “more than 100 acres of land that could be characterized as

blighted, neglected, underutilized and/or inappropriately utilized.”

Junkyards, abandoned warehouses and factories, and even the weedy remains

of the railroad tracks scarred the landscape from an earlier industrial

time. Inappropriately utilized, yes, but what a place for a kid’s

imagination — the hulking wrecks of our common history crowded against

the mirroring shore. We biked and walked among them, picking up rusting

railroad stakes, bringing them home to litter lake sand across our bookshelves.

The city had been trying to revitalize the area since long before I was

born, but was stalled by a lengthy court battle with the Central Vermont

Railroad (CVR), which owned 62 acres along the waterfront. In 1989, Burlington

finally won a huge victory in the Vermont Supreme Court. The filled-in

waterfront lands were declared to be a “public trust” and CVR

had to give them up.

After entering UVM in 1990, I found the shoreline dramatically changed.

The beautiful Community Boathouse had been finished, and by 1991 Waterfront

Park was open and Church Street foot traffic had migrated west to the

lake. Rollerbladers, bikers, and strollers conquered the margin where

transient men once slept out the winter in empty warehouses. By the time

I graduated, the bike path extended for miles, from Oakledge to the Winooski

River, and the waterfront was a place of zipping, jogging excursions for

hundreds of people a day. There were future plans, too, all “appropriate”

uses such as government facilities, parks, marinas, museums, research

centers, restaurants, and snack bars. In other words, no private industrial

development.

As I began researching Burlington history for my novel, Wilderness Run,

I realized how revolutionary this decision was. When waterways were the

great transportation arteries of our country, Burlington was a thriving

lumber town, stacks of wood piled like I-Ching characters along the water’s

edge. In 1873, there were 1,021 steamers, ships, and canal boats registered

in Burlington, and pictures of the time show a dense, crowded city surging

to the shoreline. The railroad had also nudged in at mid-century, adding

to the congestion, and when a fire burned the waterfront in 1888 it made

quick work of devastating the close-set buildings. For most of its history,

Burlington had prized function over form on its shore, but not anymore.

Food festivals would replace factories, and the tourist and recreation

economies would punch a few more nails in the coffin of New England industry.

In the last decade, the city has steadily continued its erasure of the

industrial past, taking down the old grain tower and the oil tanks. While

the overall revitalization has put Burlington high on the livable city

charts, those lost rusty relics contributed to my sense of the city’s

history when I started my novel. Wilderness Run chronicles the coming-of-age

of Isabel and Laurence Lindsey, the children of Vermont lumber barons,

at the outbreak of the Civil War. In the first chapter, they’re standing

on a castle of ice in the frozen bay when they hear the voice of a runaway

slave, and their choice to help him changes their lives forever.

I discovered the inspiration for that castle the day my three closest

high-school friends and I took the SAT. After we finished darkening endless

ovals with our No. 2 pencils, we decided to head to Oakledge and breathe

some fresh air. To our amazement, we found a twisting rampart of frozen

water spilling from the shoreline cliffs. Within two years’ time

we would all head off to different schools, our fates partially determined

by the major test we had just taken. As we climbed the ice, we felt simultaneously

giddy and precarious, full of fear and hope, which were exactly the emotions

that run through Laurence and Isabel in their own scene.

That dance of danger and possibility is what I miss most about the old

waterfront, but Vermonters are stubborn nostalgics by nature and my own

wistfulness is probably as much for the raw, unfinished awe of childhood

as it is for history.

Is our waterfront cleaner now? Yes. Is it easier to enjoy? Absolutely.

But remember how the smell of rust used to hang over the shoreline air?

Remember how the weeds dragged at your shins when you went walking and

sometimes you spied something glimmering, half-hidden, in the grass and

took it home? Remember how you called it treasure not because it was worth

a dime but because you had found it? It was yours. You found it on the

edge of the world.

—Maria Hummel (’94) is a novelist and poet living in Los Angeles.

Her first novel, Wilderness Run, was the winner of a Bread Loaf

Fellowship and an alternate selection of the Doubleday Literary Guild.