It began, as do so many stories of destruction and redemption, with fire. First the kiln that formed 300,000 bricks by the shores of the Winooski, then the fire that brought down a building and rendered those bricks to a smoking pile, nearly ending the prospects of a young university in the north woods.

Ira Allen had given land to found Vermont’s state university on the hill overlooking Burlington Bay, but for years, while the “university” was more an idea than a reality, the only things on that land were the ancient trees that covered what would later be University Green. That began to change in the late 1700s, when UVM’s first president, the Rev. Daniel Clarke Sanders, began felling trees from the Green to clear land and furnish the lumber for the framework of the President’s House, a simple wooden structure that sat for about 50 years near the present site of Williams Hall. The first class of students, four in number, lived in that house with Sanders, who constituted the entire faculty.

The university was tiny, but it engendered an outsized sense of pride in the Burlington community. Even though the town at that time had barely more than 800 residents, they managed to raise over $2,300 to begin funding the construction in 1802 of the first true university structure, University Hall.

John Johnson knew how to take in the lay of the land. Born and raised in New Hampshire, by his 25th year, in 1796, he decided to put his surveying skills to use in the wilderness to the north, and he began making his living measuring, dividing, and marking plots of property throughout the north woods. He also knew how to read a river, gauge where its flow was of greatest use, and he developed a specialty, designing mills—the long, thin structures that hugged the sides of rivers and streams throughout early New England, transforming the “free” energy of falling water to grind grain and cut lumber.

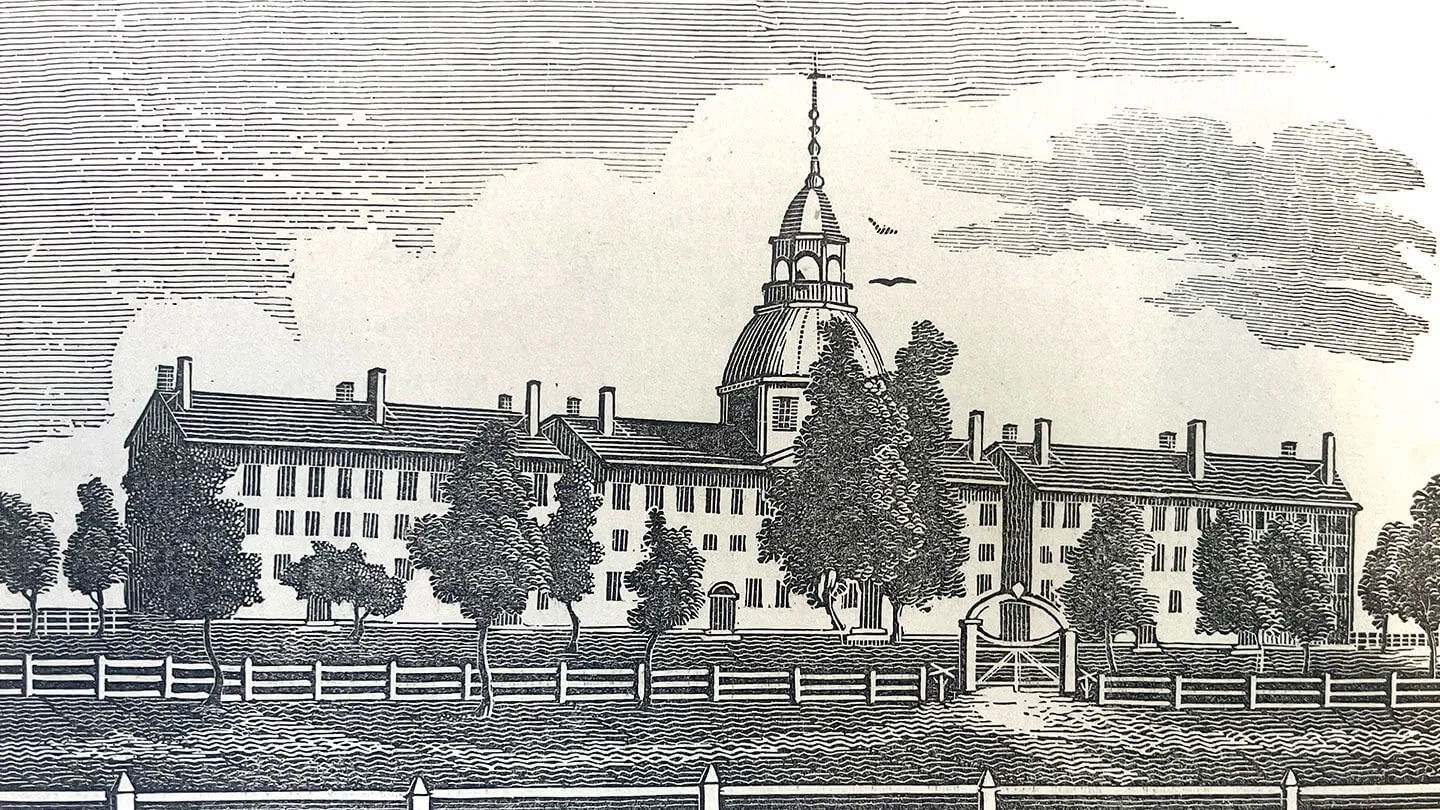

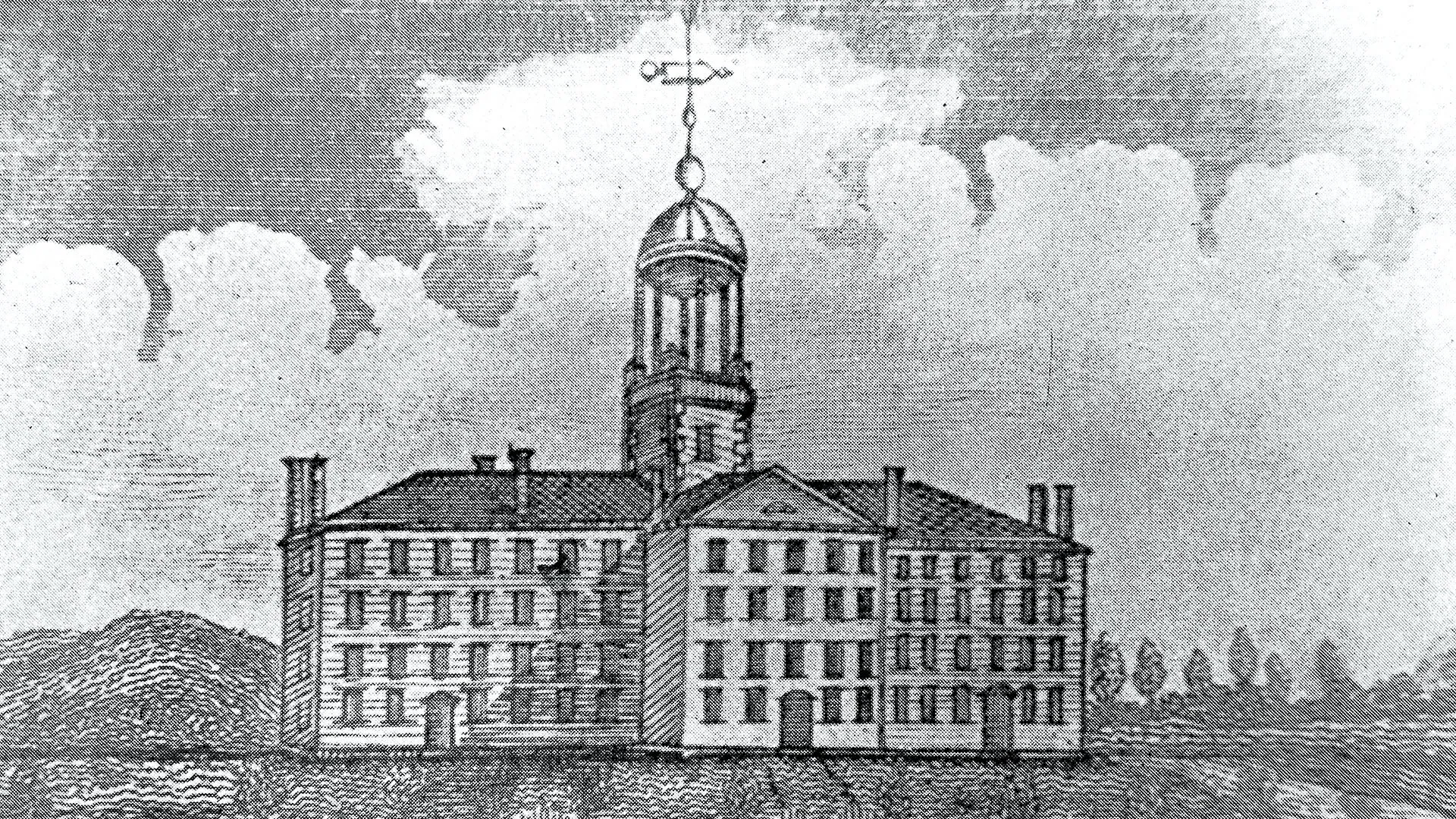

Johnson also designed and built structures, and in 1800 the university trustees contracted with him to build University Hall. From clay along the Winooski (or, what was then commonly called the “Onion River”) were fired those 300,000 bricks, which were then dragged on sleds over the snowy ground to the building site by the Green. More trees were felled from the Green and surrounding acres. The wooden frame of the structure was held together mostly with pegs—iron or steel nails were precious. By 1802 University Hall was finished: 165 feet long, 45 feet wide, with a protruding center gable, a center tower, and a belfry. Its design was loosely based on Nassau Hall at what was then known as the College of New Jersey—now Princeton. It contained everything that then constituted the university—student rooms, recitation hall, library, laboratory, and chapel.

University Hall lasted for some 22 years, while the institution limped from crisis to crisis, caused by the waxing and waning, mostly waning, of its student body. The structure probably reached its population height during the War of 1812, when classes were suspended and the hall was taken over for military use. By 1821, when the Rev. Daniel Haskel was appointed the university’s fourth president, enrollments were down, and the trustees were about to declare an indefinite suspension of activity. Haskel managed to recruit students and turn things around, briefly, until fire changed the narrative.

It all began with a few wood shavings used one night in May 1824 by a young scholar to feed the woodstove in his room at University Hall. The glowing shavings were wafted up by the draft in one of the building’s brick chimneys, and settled back down onto a corner of the roof. Soon the roof’s support structure was aflame, then the whole building was consumed. There was no substantial stream or water supply on the hill, so high above the lake. By the morning of May 28 the University of Vermont was, effectively, a smoking ruin. The devastation was too much for the Rev. Haskel. He suffered a mental breakdown and fled Vermont.

This could have spelled the end for UVM, but the university trustees and the Vermont community had other ideas. As UVM’s history of its early presidents notes, “At a meeting on June 1, 1824, at Mr. Gould’s Hotel in Burlington, the corporation bravely voted that measures should be immediately taken to erect suitable college buildings, and to raise the necessary funds for that purpose. By this time, Burlington had become more prosperous as a result of lumbering, boat building, and small manufacturing operations, and its population had grown to 2,500 people, who were once more prepared to come to the rescue of the university. In August 1824, a committee representing the citizens of Burlington announced that the sum of $8,362 had been subscribed for rebuilding a new college edifice.”

Once again, John Johnson, who by now had built himself a handsome wood-framed house on a northern corner of University Green, was employed to design and build. And this time, Johnson’s experience constructing long, thin mill buildings was put to use. The 300,000 used, charred brick from University Hall were gathered and cleaned. In barely a year more materials were ready, and construction was about to begin.

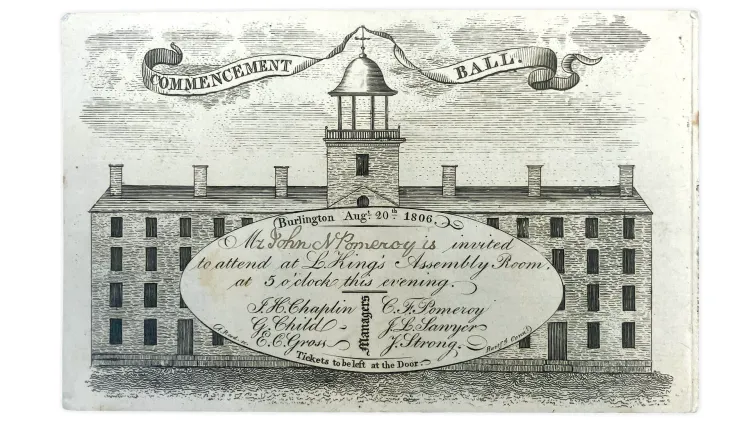

On the night flames devoured University Hall, 3,000 miles away, in France, a hero of the American Revolution, the Marquis de Lafayette, now well into his 60s, was preparing to set sail for America to tour the country one last time. Lafayette had been taken in as a protégé of General George Washington partly because he had passable English and came from a military family and had some training in the art of war. And he was also a member of the Masonic Order, as were many of the United States’ founders, including Washington. By 1824 Lafayette had managed to survive the French Revolution with his head still firmly attached, and had become a respected French elder statesman. But he longed to see what had become of the nation across the Atlantic he’d helped to found in his youth. In late June 1824 he set sail, landing in New York City in mid-August. He then, over the course of the following year, completed a monumental tour, travelling more than 6,000 miles through all the then 24 states, via horseback, carriage, and riverboat. One of the last states he visited was Vermont, and the organizers of his visit clearly intended to honor Lafayette’s position as a proud Mason.

Lafayette travelled by coach from New Hampshire over the bridge at Windsor, and was joined by Governor Cornelius Van Ness, who rode with him to Montpelier, where they stayed the night. The next day the group rolled northwestward in their carriage to Burlington, arriving in time for a formal dinner in the town. With evening setting in, the dignitaries travelled up the hill to the worksite on the edge of the Green, and Layette troweled mortar underneath a cornerstone of local redstone, watched by the assembled students, town officials, and UVM’s new president, the Rev. Willard Preston. Night was falling, so the company retired to Governor Van Ness’s attractive house, Grasse Mount, a short walk from the Green, for a late banquet. (John Johnson had designed and built Grasse Mount in 1804.) Lafayette never slept in Burlington; after dinner he rode down to the waterfront, boarded the Phoenix II, an early Lake Champlain steamboat, which saluted him with 13 cannon blasts before conveying him overnight to Whitehall, N.Y.

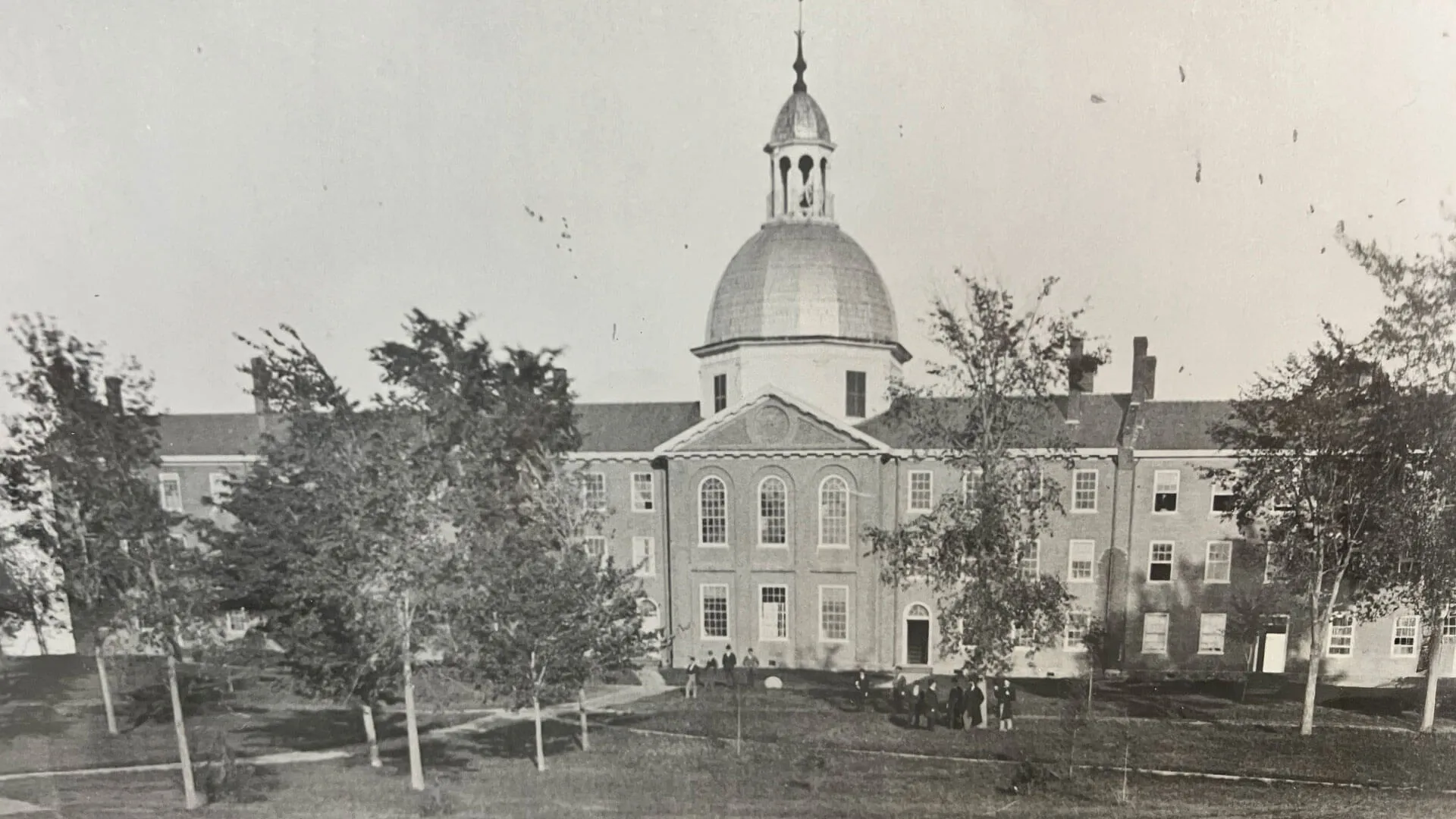

The stone Lafayette laid was at the base of the northwest corner of what was known then as “South College,” one of three structures that would rise on the site through the 1820s, with South and North Colleges built in 1825. The gap between these buildings was filled in 1829 with the construction of Middle College, an 86-foot-long structure with an arched-windowed central gabled projection, a tin-roofed dome, and a cupola in which hung a new bronze bell, cast by the Holbrook foundry in Massachusetts. (The bell now sits on a wooden mounting on the ground to the north of the building.) Legend has it that the dome was designed by UVM mathematics and natural history professor George Benedict, although John Johnson, with his intricate working knowledge of trusses, undoubtedly also contributed practical adjustments.

For about 15 years after the completion of Middle College, the three separate buildings sat in a row atop College Hill, with an eight-foot gap between structures as a precautionary fire break. In the mid-1840s, with memories of the destruction of 1824 fading, the three buildings were joined together to form one single 250-foot-long brick structure, roofed with slate. Historian Karen Dillenbeck notes that “the drab, flat, long, severe façade and windowless north and south ends earned the building’s nickname of the ‘Old Brick Mill’ or ‘Old Mill.’” The unified structure contained the whole of the university—its students’ lodging, lecture halls, chapel, museum, library, and laboratories. The only other buildings of any note at the university were the College of Medicine, then a quasi-independent entity on the north end of the Green, and the old wooden President’s House, which was struck by lightning in 1844 and burned to the ground.

Today, few people realize that UVM once had a domed central structure that stood prominently above Burlington, visible to all who approached by boat from Lake Champlain, and from miles away in the western countryside. But as commanding as the dome was from outside, it’s interior was equally impressive. By some accounts the inside of the dome was painted black and shrouded from any outside light, so that faculty and students of what was then termed “natural philosophy” could conduct galvanic experiments with electrical apparatus—one imagines Frankenstein-like sparks arcing through the darkness.

This original Old Mill would remain virtually unchanged for the next 40 years, with just some interior renovation in the 1860s to fashion more comfortable student suites. It would take the fortune, generosity, and will of a man who never actually attended UVM to bring about the next significant chapter in Old Mill history.

Stand today facing the northwest or southwest corners of Old Mill, with Lake Champlain off in the distance across the Green, and you’ll take in, in one glance, two separate versions of the building. To one side are the old, light-colored, hand-made bricks of the old back wall – some perhaps survivors of the 1802 University Hall. At the edge of the corner there’s a dramatic shift in color and texture in the brickwork. There’s an almost geologic feeling of viewing a faultline, or the meeting of two layers of rock in a highway roadcut. It is, in fact, the meeting of two architectural eras, the Federal on one (light-colored) side, the High Victorian on the other.

High Victorian came to Old Mill courtesy of John Purple Howard, a Burlington-born merchant who made a fortune in New York hotels and, in the 1880s, began giving away much of his fortune to improve his old hometown. He endowed an opera house in the Queen City, supported his sister Louisa’s Ladies Aid Society (precursor of today’s Howard Center), and looked to the top of the hill to make his most visible donation. Howard provided some $50,000 to expand and remodel the building in the style of the day, employing architect J.J. Randall of Rutland. All the floors were raised by four feet, a fourth floor for student lodging was added, with dormered windows, and the long, flat façade that earned the structure its affectionate nickname gave way to an expanded frontage in new “Winooski brick,” with new projections in the Victorian Gothic style at the ends and center, and ornate lintels of gray Isle La Motte stone above the windows. In the center of the building was an expanded chapel, one of whose stained windows, donated by the children of Professor George Benedict, depicted the dome their father designed.

The most obvious change from afar was the replacement of that dome with an ornate octagonal tower crowned with a golden finial. Howard was praised for his support of the university, but the dome was mourned through the community. The Burlington Free Press of May 18, 1882, reported: “The old College dome is no more. This morning the last vestige of the ancient landmark and surveyor’s beacon disappeared. Verily, the glory of the hill has departed.” The paper returned to this theme a few months later, writing that “numerous and sometimes pathetic have been the requests from distant and long-absent graduates of the College, that, whatever might be done with the rest of the ‘Old Brick Mill,’ its shining dome, the great landmark of the valley, might be preserved in its integrity.”

It would take years, but the “new” elaborate tower (more accurately, a belfry, since it contained the Holbrook bell that, until 1941, rang out class changes) would come to be, with passing generations, its own beloved landmark. The Old Mill of the 1880s would remain virtually unchanged until 1918, when fire again interrupted the narrative. A blaze that may have begun in a student room threatened to destroy the building, but was extinguished in time. But the fourth floor was gutted by the fire. The dormers were removed from the roof and the fourth floor was largely sealed off.

By the 1940s, Old Mill was showing its age, and the student body, due in part to World War II, had dwindled to under a thousand students. Old Mill was shuttered for two years. In the late 1940s plans began to form to “renovate” the structure. Fundraising for this effort took years, but in the late 1950s the work finally began. A new International Style building, named Lafayette Hall in honor of the cornerstone layer, rose to the east of Old Mill. The interior of Old Mill was drastically revamped, with narrowed hallways and cinderblock staircases. The bell was removed from the belfry and with it, in a way, went most of the building’s old charm.

It would take another renovation effort 35 years later to restore that charm and functionality. In the late 1980s planning began on a full-scale structural restoration of Old Mill. Thomas Visser, now a UVM Professor of History, served as the preservation consultant. Visser, aided by a cadre of students interested in historic preservation, examined nearly every inch of the building, crawling under floor beams to inspect the foundation and scraping paint from the exterior of the belfry to find samples of the original coloring. Visser produced an 82-page “historic structure report” that served as a guide to the renovation. “The whole strategy was to try to acknowledge its multiple layers of history and come up with a plan for the rehab,” Visser says. “We wanted to come up with a strategy for preserving it as much as possible, and what ended up was, in essence, a tradeoff, a sort of mitigation strategy, working with the state preservation office, to deal with the significant structural problems of the building. The result was that the interior had to be gutted.

But the mitigation for that loss of layers of historic fabric was that the university agreed to restore the exterior to its appearance as it was when it was converted into the present High Victorian Gothic style.” That preservation project, completed in 1997, resulted in a completely rebuilt Lafayette Hall, a four-story Old Mill Annex, and the functional, charming Old Mill UVM students, faculty, and staff know today, the Old Mill that Professor of English Philip Baruth, who has occupied an office on the third floor for most of his UVM career, recalls having a magical pull even from afar:

“I went to grad school in Southern California, and when my Ph.D. program was ending, I applied to 35 schools around the country,” writes Baruth. “One of those schools was the University of Vermont, and all of the UVM correspondence came from a magical place called Old Mill. I pictured it as an ivy-covered brick building beside a river with, I don’t know, a water wheel on the side. And my mother in New York, who’d married my stepfather in Arlington, Vt. — and who’d forever after kept a ‘Vermont is for Lovers’ sticker fixed to her bumper — was over the moon at the prospect. ‘The Old Mill,’ she whispered over the phone when I told her I’d landed an interview, ‘can you imagine going to work every day in the Old Mill?’ I could imagine it. And I did. Turned out there was no water wheel, but it’s been a romantic journey still and all, every day for the last 32 years.”

Editors's Note: Two-hundred years to the day after the laying of Old Mill's cornerstone by General Lafayette, the event was re-enacted on the UVM campus as a part of the series of national events taking place throughout 2025 to celebrate the anniversary of Lafayette's grand farewell tour of the country he fought to found. Read more about the 2025 event here.

Throughout this summer UVM's Silver Special Collections on the Burlington campus is featuring an exhibition of photographs and artifacts related to Lafayette's visit (including the actual trowel used in the original cornerstone laying), as well as UVM's grand 1925 centennial commemoration of the visit.