Unitarian Church (1816)

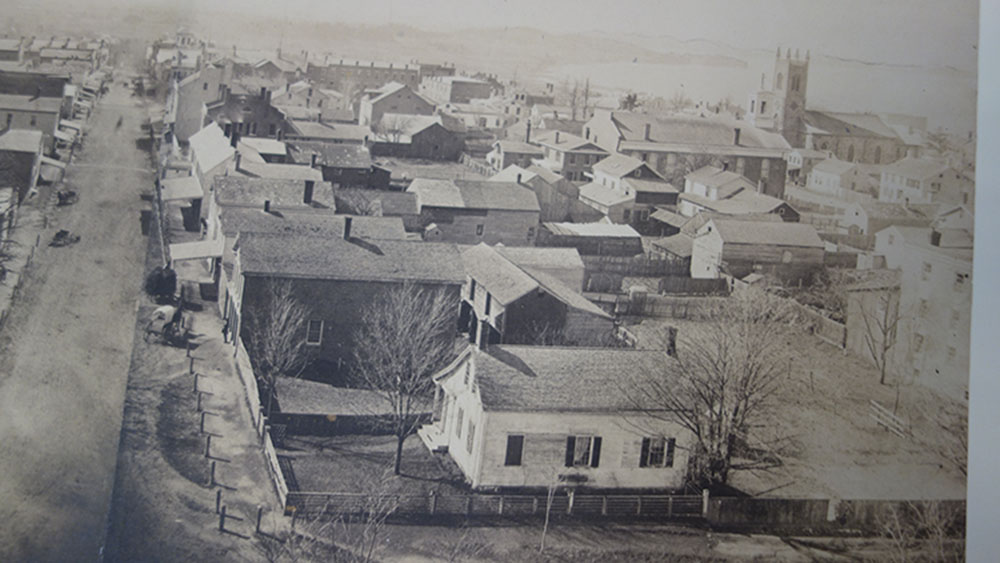

Nearly as old as the Burlington itself, the Unitarian Church is an icon for the city.1 The clock tower and steeple are landmarks for travelers to the region.

The brick building in the Federal style uses the familiar Wren-Gibbs design. The original structure is approximately 91 feet long by 70 feet wide and the tower is 170 feet high. Its foundation is dressed stone. It has a timber frame and load bearing brick walls. Large windows allow light into the expansive interior that was designed with aesthetics and acoustics in mind. The front entrance, centered in the tower, looks down the street, which is named for the church.2

Burlington’s Unitarian society pre-dates the Unitarian Church. Fortunately, the church members resolved to build a house of worship and the meetinghouse is a testament to their faith and generosity. Ebenezer T. Englesby and Horace Loomis made the first step towards achieving this goal when they purchased a five-acre lot from Chauncey Langdon on Pearl Street in autumn 1814. Englesby and Loomis, with John Pomeroy and four other partners, paid $1000 for the land.3 Burlington was, comparatively, a small community in 1814. Thickets and rough pastures surrounded the lot and there were only a few dwellings.4 The congregation raised the requisite $22,185.34 to build the church with Englesby, Loomis, and Pomeroy contributing between them the final $10,000.5 This was extraordinary generosity considering the instability and economic contraction that followed the War of 1812.

Boston architect Peter Banner submitted plans for the church on either June 28 or June 30, 1815. Contracts for the completed church reference Banner only and stipulate that the structure was completed according to his plan.6 However, the two stories of interior pillars and, originally, vaulted ceiling demonstrate that the work of Charles Bulfinch may have influenced Banner’s design.

Sinclair and Allen of Essex built the frame with timber harvested from Brown’s River Valley and the brick was locally sourced. The foundation was staked out in April 1816 and the church was dedicated on January 9, 1817. Craftsmen from the congregation completed the joinery and finish work as well as the plastering. The women of the Unitarian society raised $385 towards the bell and pulpit.7

The church’s interior and exterior changed in the years following its dedication. In 1828, the original Paul Revere and Sons bell cracked during a vigorous ringing. The bell was recast in 1828 and fully replaced in 1928 with a Meneely’s bell.8 Brick pilasters were added to the corners of the building and the ceiling and pulpit were lowered in 1845. At the same time, the “For Colored People” sign was quietly removed from the southwest balcony.9

Shortly after this progressive move, a fascinating and divisive character, Reverend Joshua Young, entered the church’s history. Young was installed to the congregation on December 3, 1852 with a $1000 salary. Recognized as a vigorous and effective preacher, Young expressed abolitionist views and extolled the evils of slavery. This was at the time when the Fugitive Slave Act and Uncle Tom’s Cabin were illuminating slavery to the North. Young boldly declared himself a station keeper on the Underground Railroad and it is likely that he and his wife sheltered runaways in their barn on Willard Street. Unfortunately for Young, his radical beliefs were also his undoing.10

Young felt compelled to meet up with abolitionist-terrorist John Brown’s funeral procession in Vergennes. Young continued with the procession to North Elba, NY and delivered to Brown the usual rites of honorable burial on December 8, 1859. Young had never met Brown but he was the only ordained minister present at the burial. Upon his return to Burlington, Young stated: “Blessed are those who are persecuted for righteousness’ sake.” Young’s congregation did not share this sentiment and he was shunned. Women in the church accused him of being an anarchist, traitor, and infidel.11 Young resigned in 1863; adamant that he had preached the full gospel in Vermont.12

The church made extensive changes and improvements between 1845 and 1872. The pine shingled roof was replaced with slate in 1863. A substantial interior change was the removal of the large arched window behind the pulpit in 1868. In 1872 the clock was replaced with a new Howard clock and a fourth dial was added to the tower. Considered a traditional feature in churches, stained glass windows were not installed until 1894. White paint returned to the church’s exterior trim in 1916 which remains there today.13

The tower has been struck by lightning a number of times. A 1907 strike damaged the steeple and its new copper roofing.14 A 1924 strike was sufficient to split one of the eight-inch framing timbers end to end.15 The most devastating strike was on August 17, 1955.16 Rot in the framing, combined with the lightning damage, caused the steeple to begin leaning. The trustees made the difficult decision to have the original steeple taken down in 1956.17 The church was eventually closed until the steeple was rebuilt in 1958.18 Gilbert Small Co. of Boston drew the plans and Barr and Linde supervised construction. The replacement steeple is a replica of the original with the exception of its steel framing. Church members and the Burlington community paid for the $55,000 project.19 A 1967 newspaper article describes the church as “a symbol of dignity, serenity, and integrity of which all who belong in Burlington can be proud.”20

Changes to the church since the 1940s have been directed at restoring the church to its original simplicity. The church has received necessary updates such as electric heating and complete fireproofing in an $85,000 1963 project.21 The artisanal construction of the church and its strong, local materials, coupled with the support of the Burlington community, ensure that Unitarian Church will continue to monitor Church Street.

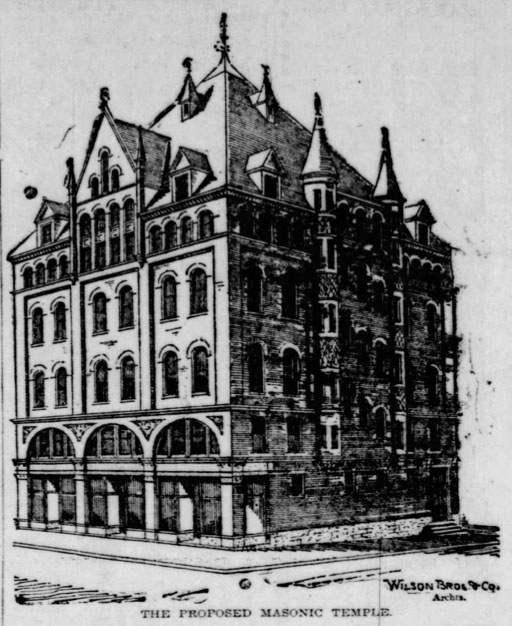

Masonic Temple (1898)

South and slightly to the west of the Unitarian Church looms the Masonic Temple. The five-story, pyramidal roofed Richardson Romanesque edifice dominates the northern end of Church Street.22 The arched store fronts in its eastern elevation and the windows that climb with its northern stair case are among its distinctive features. The Willard’s Ledge stone and locally sourced brick bind the structure to the Burlington landscape.

On January 10, 1868, the Grand Lodge of Vermont selected Burlington with a two-thirds majority vote as the site for a Masonic Temple. In 1894, the one hundredth anniversary of the Grand Lodge, the City of Burlington Board of Alderman passed resolutions allowing them to gift a piece of property to the Masons of Vermont.23 Brother Daniel Nicholson became the leader of the project and he selected Wilson Brothers and Company of Philadelphia to be the architects. Wilson Brothers and Co. designed a UVM dormitory and the Dr. Williams science building.24 At the same time, the Grand Lodge stipulated that voluntary subscriptions from the citizens of Burlington were necessary to secure the project.25

Fortunately for Church Street, engineers quickly realized the Winooski Avenue and College Street lot selected for the project had been filled and was not sufficiently stable for construction. A lot on Church Street at the corner of Pearl Street was then selected but it was larger and more expensive. This larger lot increased the size of the temple to five floors and the citizens of Burlington were required to subscribe $5000. The Masons voted unanimously to build the temple on Church Street believing it was the best site in the city and that the stores and offices would rent for a good price.26 W. B. McKillip and A. E. Richardson pledged the final amount to move the project ahead.27

The site contained a home and a commercial building dating back to at least 1830.28 The Johonnott family occupied both structures from at least 1862 until 1877.29 3 Church Street was a private residence until construction of temple. A variety of businesses occupied 5 Church Street including a leather dealer and multiple confectioners. The final tenant at 5 Church Street was a cigar manufacturer named John Seith.30 Demolition and clearing of the site began on Saturday July 11, 1896.31

The temple was completed in 1898 at a total cost of $87,500.32 At the laying of its cornerstone, Mayor Peck stated: “A worthy Masonic Lodge is a desirable factor in any community. It stands pledged to the development and training of those things in man which are the noblest and best.”33 However, the enormous expense of owning and operating the temple weighed on the Masons. As early as 1914, the Grand Master suggested selling the temple because of the heating costs. A fire on February 3, 1933 nearly consumed the entire building. Shortly after the fire, the damage was estimated at $60,000.34 In the 1960s the membership of the Free Masons began to wane across the nation. The Vermont Free Mason membership declined as well and by 1970 the meetings had moved from the secret chamber in the temple to a Ramada Inn where heat was included, making the temple obsolete.

By 1984, the temple was in need of renovation and updating. The building had no insulation and there were disjointed improvements and modifications throughout its interior. The One Church Street Partnership formed and proposed purchasing the temple and renovating it for office and retail use. In the same year, R. E. M. Development proposed the massive Burlington Plaza Hotel on the St. Paul Street side of the block. Peter Collins, of the One Church Street Partnership, argued that scale of the hotel would affect the Masonic Temple historic site.35 Fortunately, the hotel was never built and the partnership received $3.1 million in industrial revenue bonds towards the $4 million necessary to purchase and renovate 50,000 square feet of office space.36 This project promised to support the revitalization of the Church Street marketplace and Burlington.37

The renovations began with lifting the building to install a new steel and concrete foundation. The interior was reorganized into appropriately dimensioned offices, hallways, and stairs compliant with fire and safety codes. Necessarily, the pyramid roof was blocked off with a false ceiling. The southern windows, bricked off in the 1940s, were opened up. In 1989, following the renovations, the temple was appraised at $2,510,900 and taxed at $3,013,000.38 The One Church Street Partnership remains committed to the Masonic Temple and its value to Church Street and the city of Burlington.

135/137 Pearl Street

The present structure at 135-137 Pearl Street dates to at least 1885 according to the Sanborn Fire Insurance Map.39 The Sanborn maps illustrate 137 Pearl St. as a dwelling and show it was used as commercial space and a rooming house in the late 19th and early 20th centuries.

In 1921, James P. Dower, an undertaker, moved his funeral home to 137 Pearl Street. Formerly a rooming house, alterations transformed the lower floor into a funeral parlor and the upper floor became an apartment for Dower and his family.40 When the Dower Funeral Home moved to Elmwood Avenue, Angelo Sultanos’ Community Fruit Store became the lower floor tenant.41 In 1933, interior improvements were made to obtain a first-class liquor license. These included additional tables, booths, and the additional serving facilities.42

From 1927 on, 135-137 Pearl Street has been a combined residential and commercial space. Owners and tenants have made interior and exterior changes over the years. In 1960-61, The Corral Restaurant moved into the lower floor. This tenant brought improvements such as a banquet room with rheostat lighting, new windows and doors, and booths which were incorporated into the counter for fast service.43 When a fire closed Tony’s Pizza and damaged the upstairs apartment in 1971, the Black Angus Steak House moved in and restyled the interior.44

In 1983, four business partners purchased the two-story building that was surrounded by pavement and parking spaces.45 This partnership created Pearl’s Bar. Pearl’s Bar established itself as a gay and lesbian friendly bar in a college town. Robert Toms and Craig Mitchell purchased the bar in 1995 and renamed it 135 Pearl.46 This ownership added a performing arts space to the bar and increasing emphasis on openness and inclusivity. In 2006, Toms closed 135 Pearl for financial reasons and to focus on his acting. Toms also cited the increasing acceptance of the LGBTQ community in mainstream society as a force that, in some ways, made 135 Pearl unnecessary. Terry Moran purchased 135-137 Pearl St. in 2006 for $375,000. Moran brought in the Papa John’s Pizza which remains there today with apartments in the floor above.47

125 Pearl Street

In 1830, E. L. Farrar built a pottery business on the south side of Pearl Street between Church Street and St. Paul Street. Later, the Ballard brothers expanded the business and in 1874 Franklin Woodworth purchased it. At the time, the only other commercial pottery operation in Vermont was in Bennington.48 The pottery business thrived under Woodworth and produced high quality stoneware that survives in collections today. Unfortunately, Fred Woodworth, who took over for Franklin in 1894, lacked his father’s business acumen.49 At the same, inexpensive mass-produced glassware and metal products were making utilitarian pottery obsolete.50 The business quickly failed and the pottery and land were sold in 1896.

In 1906, the Johnson-Richardson Company rebuilt and refit the property to manufacture a different product, Dy-o-la dye.51 Dy-o-la operated at the same location in Burlington until the company was sold in 1932.52 Eventually the Moquin bakery moved their production to the building Dy-o-la previously used. This endeavor was brief as a fire destroyed the wooden building and all of the bakery equipment in January 1937. Fortunately, the fire did not spread to the 135-137 Pearl Street building which contained tenements and a business.53

Recognizing the property as part of a developing retail section, the Ridgewood Realty Company purchased the Dy-o-la lot to build a six thousand square foot supermarket facing Pearl Street in 1937.54 This A & P brought a number of changes to Burlington. Wright and Morrissey Contractors built the steel frame and cinder block structure with a parapet roof in two months. There was a bowling alley in the basement, HVAC system, and ample parking. The supermarket also boasted new conveniences such as shopping carts and the, now ubiquitous, cashier-checker method.55 The Pearl Street A & P closed in 1974 at a time when A & P was shutting down a number of their Vermont locations.56

After the supermarket closed, the lot transitioned to being a home for nightclubs such as “Fooshaus”, “Sting”, and “Neutral Grounds.”57 During this time the building expanded in size to 21,000 square feet. The final nightclub was “Great Escape” before the building became vacant in 1984. At that time, Robert Miller and R. E. M. Development proposed building an immense 250 room hotel along St. Paul Street between Pearl Street and Cherry Street.58

From its genesis, this project had a polarizing effect on the neighborhood and it permanently changed the St. Paul Street/Pearl Street corner. In October 1984, tenants received eviction notices and were informed that demolition would begin in November. Prior to demolition, the neighborhood with a rich commercial and residential history. Among the longest occupants, Charles L. Nelson and Henry J. Nelson manufactured furniture on St. Paul Street four doors north of the Catholic church from 1835 to at least 1869. The retail business continued in Burlington and at its height, Nelson Company stretched across the block from St. Paul Street to Church Street with its storefront on Church Street. The business was sold in 1910 after H. J. Nelson’s death.59 J. C. Penney Automotive was located at the corner of St. Paul Street and Cherry Street for many years. 119 Pearl Street was an intact circa 1810 Federal style home with residential and commercial tenants. Red asbestos siding concealed its white clapboard and its demolition was largely unnoticed. 14-16 St. Paul Street, a circa 1890 Queen Anne style duplex was also destroyed for the hotel project. The A & P building, which housed the first supermarket in Burlington, was also necessarily destroyed.60 In total, eleven units of housing were lost to the project. Miller and business owners believed the hotel would be a boon to the economy. Neighborhood residents objected to eviction and the size of the hotel. Cathedral Church of St. Paul opposed the project because of Miller’s intent to close St. Paul Street to public traffic.61

Ultimately, Miller abandoned the hotel project. Alderman Peter Lackowski responded: “That was a dirty trick…it’s a darn shame to lose that housing.”62 Miller stated: “They say they aren’t anti-development, but they put on so many controls it really shows they are.”63 Instead, Miller began the St. Paul Place project which included 450 parking spaces and 125,000 square feet of office space.64 Construction stopped at the parking garage phase which the State of Vermont purchased in 1991 for $5,050,000.65

In 1992, the St. Paul Street site between Pearl and Cherry Streets was confirmed as the home for the future Vermont State Office Building. The total cost of the project was $12.3 million and part of a state pledge to promote development in cities. Extreme competition in the construction industry at the time made it a prudent time to build. The John J. Zampieri State Office Building received its finishing touches in May 1993. The Downtown Transit Center on St. Paul Street opened Thursday October 13, 2016.66

NOTES

1. “Burlington’s First Church Building Has Served 150 Years,” Burlington Free Press, January 20, 1967.

2. Elizabeth Kirkness, “Electricity Modernizes Oldest Church in City,” Burlington Free Press, March 13, 1964.

3. William W. Fenn and Charles J. Staples, The One Hundredth Anniversary of the First Congregational Society Unitarian, Burlington, Vermont (Burlington: Free Press Printing Company, 1910), 35.

4. “Free Press Features 1st Unitarian Church,” Burlington Free Press, December 24, 1965.

5. William W. Fenn and Charles J. Staples, The One Hundredth Anniversary of the First Congregational Society Unitarian, Burlington, Vermont (Burlington: Free Press Printing Company, 1910), 36.

6. Reverend Gary Kowalski, “Pillars and Windows,” The First Unitarian Universalist Society of Burlington, (2009) http://www.uusociety.org/sermons?s=118 (accessed November 7, 2017).

7. “Unitarian Church is 100 Years Old,” Burlington Free Press and Times, January 8, 1917.

8. “Old Church Bell Has Interesting Story,” Burlington Free Press and Times, November 30, 1928.

9. Winston Way, “Open House Ends Unitarian Anniversary Year,” Burlington Free Press, November 11, 1967.

10. William W. Fenn and Charles J. Staples, The One Hundredth Anniversary of the First Congregational Society Unitarian, Burlington, Vermont (Burlington: Free Press Printing Company, 1910), 45.

11. “Burlington’s First Church Building Has Served 150 Years,” Burlington Free Press, January 20, 1967.

12. Leonard Twnyham, “A Martyr for John Brown,” Opportunity Journal of Negro Life 16, no. 9 (1938): 265-267.

13. “Unitarian Church is 100 Years Old,” Burlington Free Press and Times, January 8, 1917.

14. “Lightning Struck Steeple,” Burlington Free Press and Times, June 27, 1907.

15. “Struck by Lightning,” Burlington Free Press and Times, June 23, 1924.

16. “Lightning Stuns Landry on North Ave.,” Burlington Free Press, August 18, 1955.

17. “Unitarians Will Decide Fate of Steeple,” Burlington Free Press and Times, January 6, 1956.

18. “Church Steeple Passing into History,” Burlington Free Press, February 2, 1956.

19. “Unitarian Church Steeple Heads Church St. Again,” Burlington Free Press, May 9, 1958.

20. “Burlington’s First Church Building Has Served 150 Years,” Burlington Free Press, January 20, 1967.

21. Elizabeth Kirkness, “Electricity Modernizes Oldest Church in City,” Burlington Free Press, March 13, 1964.

22. David J. Blow, ed., Historic Guide to Burlington Neighborhoods, (Burlington: Chittenden County Historical Society, 1990), 43-44.

23. Joseph K. Stevens, The Temple Built by Hands, 1794-1897 (Burlington: Grand Lodge, 1978).

24. “The Masonic Temple,” Burlington Free Press and Times, June 10, 1896.

25. “The Masonic Temple,” Burlington Free Press and Times, June 2, 1896.

26. “The Masonic Temple,” Burlington Free Press and Times, June 18, 1896.

27. “The Masonic Temple,” Burlington Free Press and Times, July 8, 1896.

28. Plan of Burlington village, Special Collections, University of Vermont Library, http://cdi.uvm.edu/collections/item/Burlington_Young_1830 (accessed November 07, 2017).

29. The village of Burlington, Vt, Special Collections, University of Vermont Library, http://cdi.uvm.edu/collections/item/Burlington_FreePress (accessed November 07, 2017); Burlington, Burlington City Directory 1877-78, (Burlington: Free Press Association, 1878): 68.

30. Burlington, Burlington City Directory 1896, (Burlington: L. P. Waite and Company, 1896): 291.

31. “City and Vicinity,” Burlington Free Press and Times, July 13, 1896.

32. Chris Lavin, “Secrets of the Temple,” Burlington Free Press, October 13, 1985.

33. Grand Lodge of Vermont, Proceedings of the Ceremonies of Laying the Corner Stone of the Masonic Temple (Burlington: Free Press Association, 1897), 8.

34. “Masonic Temple on Church Street Threatened by Fire,” Burlington Free Press and Times, February 4, 1933.

35. Leslie Brown, ‘Architect Reveals Plan of Hotel to Fill “Cavity” in Retail District,’ Burlington Free Press and Times, March 23, 1984.

36. Rob Eley, “VIDA Approves $8.5 Million in Bonds for Weybridge, New Haven Hydros,” Burlington Free Press, August 27, 1984.

37. Susan Youngwood, “VIDA Sets Record for Loans, Grants,” Burlington Free Press, December 15, 1984; “Did You Know?,” Burlington Free Press, January 13, 1985.

38. Enrique Corredera, “Burlington wins tax dispute,” Burlington Free Press, June 24, 1989.

39. Burlington 1885, sheet 03, Special Collections, University of Vermont Library, http://cdi.uvm.edu/collections/item/btvfi_1885_003 (accessed October 24, 2017); 135/137 Pearl St. Property Search, “Property Search,” City of Burlington, VT, https://property.burlingtonvt.gov/PropertyDetails.aspx?a=5344 (accessed October 23, 2017).

40. “New Provision Store,” Burlington Free Press and Times, October 7, 1921.

41. “J. P. Dower Moves Funeral Home to Elmwood Avenue,” Burlington Free Press and Times, October 17, 1927; “City News,” Burlington Free Press and Times, February 1, 1928.

42. “City Attorney Makes Ruling on Beer Licenses,” Burlington Free Press and Times, June 26, 1933.

43. “Restaurant Incorporated in Burlington,” Burlington Free Press, November 8, 1960; “New Corral Restaurant Invites Public to Opening Festivities,” Burlington Free Press, January 6, 1961.

44. “Fire Damages Tony’s Pizza,” Burlington Free Press, January 25, 1971; “Opens Friday,” Burlington Free Press, May 13, 1971.

45. NCPR News, “Remembering a gay landmark in Burlington,” North Country Public Radio, (2012): https://www.northcountrypublicradio.org/news/story/20068/20120629/remembering-a-gay-landmark-in-burlington.

46. Cathy Resmer, “135 Pearl, Unstrung,” Seven Days, (2006) https://www.sevendaysvt.com/vermont/135-pearl-unstrung/Content?oid=2127268.

47. John Briggs and Brent Hallenbeck, “Landmark gay-friendly bar closing,” Burlington Free Press, May 10, 2006.

48. W. S. Rann, History of Chittenden County Vermont (Syracuse: D. Mason and Co., 1886), 474.

49. Elizabeth Kirkness, “More on Woodworth Pottery – He Had a Crusty Nature,” Burlington Free Press, March 28, 1966.

50. “Remember When – Pottery served everyday purposes,” Burlington Free Press, July 8, 1997.

51. “Johnson-Richardson Co.,” Burlington Free Press and Times, October 6, 1906.

52. “Dy-o-la Company Sold to N. Y. Concern,” Burlington Free Press and Times, March 28, 1932.

53. “Fire Destroys Moquin Bakery,” Burlington Free Press and Times, January 8, 1937.

54. “A. & P. is to Have Super Market in Large New Building on Pearl Street,” Burlington Free Press and Times, December 24, 1937.

55. “Fanny Farmer, Carroll Stores to Open Here,” Burlington Free Press and Times, February 26, 1938; “New A. & P. Super-Market and Bowling Arena to Open Today,” Burlington Free Press and Times, March 11, 1938.

56. “Pearl Street A & P Closes Tonight,” Burlington Free Press, August 10, 1974.

57. Scott Mackay, “Revenue Sharing Approved for Garage,” Burlington Free Press, March 22, 1977.

58. Leslie Brown, ‘Architect Reveals Plan of Hotel to Fill “Cavity” in Retail District,’ Burlington Free Press, March 23, 1984.

59. “A Quarter of a Century,” Burlington Free Press and Times, February 1, 1988; “Nelson Store Sold,” Burlington Free Press and Times, May 9, 1910.

60. Matt Cohen, “City Losing Its Valuable History,” Burlington Free Press, January 23, 1985.

61. “Why We Objected,” Burlington Free Press, June 4, 1985.

62. Susan Youngwood, “Miller Says He Will Leave Vacant Lot Undeveloped,” Burlington Free Press, May 7, 1985.

63. “Quote of the Week,” Burlington Free Press, May 26, 1985.

64. Ellen Neuborne, “As development cools, Burlington developers scramble,” Burlington Free Press, May 15, 1989; Ellen Neuborn, “Burlington: Lots of parking here,” Burlington Free Press, November 26, 1989.

65. “Real estate transactions: Burlington,” Burlington Free Press, January 19, 1991.

66. April Burbank, “New bus station opens up in downtown Burlington,” Burlington Free Press, October 14, 2016.