Where do ideas for TV shows come from? Sometimes people ask this because TV programs occasionally seem strange; in the 1960s, for example, there was a sitcom called My Mother the Car, about a man whose mother was reincarnated as a talking car. But probably more often people ask this because TV shows can be so predictable and so imitative of each other. Right now on TV, for example, there are at least three sitcoms about ordinary working class married men and their families; in each case, the men are overweight comedic wiseguys and their wives are improbably thin and beautiful. How does this happen?

Does TV give the audience what it wants? Only sort of ....

Media industry executives like to say that they are just giving the audience what it wants. They just read the ratings and respond accordingly, they claim. There is a certain kind of truth to that, but there are problems with "the audience gets what it wants" argument, too. Sometimes high ratings are not welcome. In the early 1980s, for example, there was a lot of concern about nuclear weapons in the public, and ABC thus made a made-for-TV movie called "The Day After," a drama about what it would be like after a nuclear war. The movie got huge ratings because people were concerned and curious, but it ran with almost no advertisements; no advertisers would buy time because, understandably, nobody wanted their product associated with nuclear holocaust. So the program got high ratings, but it was an economic disaster, and no network has done anything like it since. TV tries to give people some of the things that they want, but the audience sometimes wants things that TV won't give them.

An even more important problem with the "audience gets what it wants" argument is that, when ideas for new programs are created, there generally are no direct ratings for a program. Ratings measure how many people watch an existing program; when someone approaches a television executive with an idea for a new TV show, there are no ratings to work with. And the fact of the matter is that roughly two thirds of all new TV shows don't make it through their first full season; by their own standards of ratings success, therefore, TV executives are more often wrong than right about what people want.

The Television-Industrial Complex

To understand where program ideas come from, it helps to know this: program producers must sell programs to a system before they can "sell" it to the audience. In the old television system of the USSR, there were censors who could press a button to cut off a broadcast if anyone did anything politically objectionable on TV; the amazing thing, however, was that the censors hardly ever had to use their power, because over time people who worked for Soviet TV soaked up the values of the system and generally learned to support it as part of their professional activity. The American television entertainment industry has no direct government censors, but like many creative industries, it also is a system; it has a particular structure, and people who work in that structure also tend to soak up its values. It is not just an open market of lots of folks selling their wares; it is a loosely coordinated system centered within specific corporations and operating by certain rules of the game. It is what sociologists (and your textbook) call a set of organizations (like television networks and advertising agencies) that operate within specific institutions(like the advertising system or the Hollywood-based production system). Sociologist Todd Gitlin has called the system of American television entertainment "the television-industrial complex."

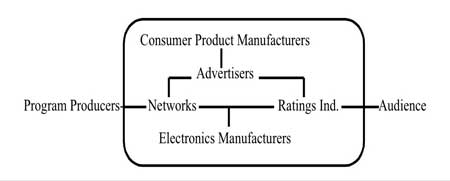

Look at this diagram of the television-industrial complex. If you have an idea for a new TV show that you think will be brilliant and hugely popular, you can't just go out and show the program to the audience to see if they like it. Typically, you first have to "pitch" your idea to a network executive, one of a handful of people who works for a major network (like CBS or Fox) and whose job it is to develop new programs. In theory, if the executive likes it, he or she asks for a "treatment" or a longer description of the show, and if that seems good, he or she might ask for a script, and then might fund a pilot episode, and finally a few episodes for actually running on the air. At each stage, however, particularly as the investment of time and money goes up, more and more people get involved in the process, and start to have input. Executives may want to change parts of the idea, or change it to suit a particular actor, or whatever. So throughout this process, you have a group of people, each of whom is worried about things like their own career, and none of whom has a hotline to the hearts and minds of the audience; everybody involved is guessing. Given that everybody is to some extent guessing, you can see how institutional constraints come in: network executives are worried about pleasing advertisers most of all, and to some degree their parent corporations (NBC is owned by General Electric, for example), and all of these people are operating within a general economic system based on selling consumer products. So, if you're a TV producer with an idea for a TV show (on the left of the chart), you first have to sell it to a group of people working within the box -- the tv-industrial complex -- before you ever get access to people on the other side -- the actual audience (on the right of the chart).

Understanding the Influence of Advertising on Program Content: Intentional vs. Structural Influence

It's true that advertisers have an enormous impact on the character of television, but it is important to specify exactly what "influence" means. Most people tend to think that if you have influence over something, it's because you do so intentionally, deliberately; you want something to happen and you make it so. Advertisers have on occasion had this kind of influence. But, as we will see, intentional influence is not the only kind of influence, or even the most important kind of influence.

Anthology Dramas and Direct Influence

Direct influenceis when advertisers simply tell TV producers what to do. At one time, advertisers did directly control entire programs on TV. In the 1950s, when TV was still a relatively new technology, advertisers would sponsor and produce entire programs; TV programs would truly be "brought to you by Chevrolet" or some other advertiser, and the show would not only have advertisements for products but would often enough be organized around products. One of the popular program formats in the early 1950s were "anthology dramas," that is, shows presented by a certain sponsor that would have a new story with completely new characters etc. every week. Some of the shows were quite good, but having advertisers in total control also created absurdities. For example, there was strong pressure to create happy endings -- in a way, to lie about life. A director of an anthology drama called Fireside Theater said at the time, "We sell little pieces of soap, so our approach must be the broadest possible . . . we never take a depressing story."

So, for example, in 1953, Schlitz Playhouse proudly presented what it said was the first Hemingway play to appear on TV, "Fifty Grand." Hemingway's story, however, was originally a gritty tragedy about a boxer, who bet against himself and deliberately threw a fight in order to win some money. In the Schlitz version, the boxer bets on himself to win, and then loses the fight, and thus learns about the evils of gambling, and goes back home to his wife to live happily ever after. Another example was when the first Faulkner story to appear on TV, "The Brooch," was sponsored by the Lux Video Theater. Faulkner's original story was about man who was a mama's boy, who permitted his mother to rule over his wife; when his wife left him he realized the nature of his unending dependence on his mother, and killed himself. In the TV version, he was presented as a nice young kid who married the sweet young thing from next door; when the mother tried to interfere in their lives, the kid stood up to her, and the mother gave in, and -- once again -- they all lived happily ever after. This is literary frontal lobotomy. But it is less common than you might think.

Series programming and structural influence

Structural influenceis when the system within which something is produced has an effect, whether or not it is intentional. An example can be seen in the fact that, as the 1950s progressed, advertisers no longer sponsored entire programs, but the way in which programming evolved nonetheless bore the stamp of advertising. For example, as television quickly spread into American's livingrooms in the 1950s, more and more people became television watchers, more and more money became involved, and advertisers began to become nervous about exactly what they were spending their money on. One of the problems with anthology dramas is that their audience was hard to measure. Because everything was different each week -- different setting, characters, and story -- ratings were unpredictable: some weeks many people would tune in, other weeks few. Advertisers pay for future audiences; they'd like to know, not just who watched last week, but who will watch next week (and next month).

This was the context when a struggling Hollywood actress named Lucille Ball created a comedy show called "I Love Lucy," starring herself and her husband in which the "situation" -- the set, the characters, the tone -- were the same each week, and what varied were simply the plots. She thereby basically invented the sitcom. The program was wildly popular, and transformed the industry. It helped that Lucille Ball was often wickedly funny, but it was also important that her audience was more or less the same each week: it was not just a big audience, but a reliable and predictable one. Anthology dramas were (sometimes) popular too, but they weren't predictable, because they varied so much. So after a few years, anthology dramas disappeared. Situation comedies about goofball families, however, are still all over the television schedule, a half century later.

The moral of this story is that the difference between sitcoms and anthology dramas wasn't about the audience; both kinds of show were popular. The difference had to do with the structural needs of the advertising system for predictability. Advertisers did not intend or force sitcoms to rise to the top. But the rules of the game determined by the structure of advertising support pushed programming content in a particular direction. It was a structural effect, not a direct, intentional one. So if you want to understand why TV is the way it is, you need to look at the structure of the system.

Television Structure and the Industrialization of Culture

TV's structure is determined, not simply because it's commercial, but because it's produced industrially, like washing machines, cars, and stereos -- i.e., its built according to standardized formula, with standardized replaceable parts. Shakespeare's plays, some of the greatest works of Western civilization, were commercial in the sense that he wrote them to make money. But Shakespeare made his money by selling tickets to audiences, not by selling audiences to advertisers of consumer products. And he knew his audience fairly directly (he acted in some of his own plays).

Making TV shows is a highly routinized, mechanized, and collective process. There's a cherished myth we have about artists: that works of art are done in isolation, by creative geniuses working alone. We get told in high school about Nathaniel Hawthorne writing the Scarlet Letter, alone, at home in a house in the woods of New England, late at night in front of the fire. Or about Hemingway writing his novels and short stories with number two pencils in a small lonely flat in Paris. Artistic creation in television is in many ways the opposite of this myth. Just about everything is done in groups. Instead of the story of an artist working alone, the story of the creation of a TV program is a story of constant meetings, arguments, and struggles. Everyone from network executives on down can get involved in nitpicking details such as the phrasing of a particular line of dialogue. And no one in the system can know their audience in a face-to-face way the way Shakespeare knew his; like all mass media, broadcast television operates across a huge separation between creators and audiences.

The Routinized Character of TV Production

Writers for a television show are often freelance; they contract to write a certain number of scripts for a production company, but are not employess of that company. They usually work, not with directors, but with the producers, and usually work with very tight guidelines. They are given the characters, a set of general ideas, and often a plot line, and their task is just to actually write the dialog. The process is a little more creative than just filling in the blanks, but only a little. Most episode writers are modest about what they do. One experienced television comedy writer has said, "you don't have to have talent to write for television. I thought it was writing, but it's not. It's a craft. It's like a tailor. You want cuffs? You got cuffs." Writing for television does take a certain kind of skill, but its not so much what we think of as literary genius as it is an ability to write scripts to order, scripts that can be produced within a week, within a set budget. Writing episodes for television series is on the lowest level in terms of pay and status for television writers in Hollywood; writing pilots are a little higher on the totem pole (it's a more creative job; you're not just filling in the blanks, because in a pilot you have to create the characters and settings as well as a plot).

In general, people who make TV shows are faced with numerous budget constraints, deadline constraints, etc., that are set neither by artistic purposes nor by "what the audience wants" but by a bunch of corporate managers (network executives) who are concerned with pleasing other corporate managers (especially advertisers). Because of these constraints, there's a strong push to industrialize production, to do things cheaply, efficiently, and according to standardized formulas. This shows up in repetition -- repetition of program formulas, use of the same actors, and so forth. It even shows up in special effects: next time you're watching an action show on TV and a helicopter flies behind a big building, you can be almost certain that the helicopter is about to explode; TV producers can not afford to actually blow up helicopters (even models), so they fly one behind a building, turn off the camera, fly it away, turn the camera back on, and set off a colorful explosion in the appropriate place.

Television, then, is a fairly predictable medium. You know that a principal character in an episode of StarTrek or Alias will never die, no matter how many life-threatening experiences they go through. In an action show, you can usually tell if they're going to get the bad guys at the end of a scene by looking at your watch; if it's half hour into an hour-long program, they won't, but if the program's almost over, they will. In fact, the idea that shows have to fit into half- or hour-long segments is about the convenience of the system, not about pleasing the audience; it's a difficult format for telling stories, because a rigidly determined length reduces the capacity for surprise, but it's convenient for program schedulers and advertisers, because it divides the schedule up into a predictable grid. (Imagine if all novels had to be exactly 150 pages long, no more, no less.)

The reason for all this predictably, it needs be said, is not that television executives are unimaginative or unintelligent. The reason is, in a nutshell, corporations like safe bets, they don't like gambling with large amounts of money. Hence, it's the system that is resistant to experimentation and novelty.

The Creation of Program Ideas: Spinoffs, Copies, Recombinants

Where do program ideas come from? Officially, they come from producers, who try to sell program ideas to the networks (the pitch). If the networks are intrigued, then they may pay to have a pilot produced; and if they like that, then they'll let the show go on the air. But the network executives usually have preconceived notions about what they want, and producers thus try to think up programs that fit the networks' preconceived notions (e.g., cop shows). And in television, the saying goes, nothing succeeds like success; Network executives are much more likely to invest in formulas that they think will be successful, and the only real measure they have of success is program formulas that have already been successful. It's this fact that leads to the rather incredible level of spinoffs and copies in television programming.

Spinoffs: People in the TV industry believe that people watch television programs because they like the characters, especially in comedies; therefore, if a program is successful, the reasoning goes, it must be because the characters were good. What would be a safer bet than creating programs based on existing characters? Hence: spinoffs. The predominance of the spinoff formula sometimes makes the history of American TV shows read like the "begats" section of the Bible: the Mary Tyler Moore show begat Rhoda, Lou Grant, and Phyllis; All in the Family begat the Jeffersons, Maude, and Gloria; Happy Days produced Laverne and Shirley and Joanie Loves Chachi; Cheers begat Frasier.

Copies: Copies simply reproduce successful program formulas rather than characters. This is also very common in Hollywood. One TV writer has said that most program pilots "are to creativity what Xeroxing is to writing." As of this writing, spy and crime/detective shows are proliferating on TV, as is a fondness for striking, painfully thin, and serious-faced female actors who catch bad guys while wearing skimpy tops.

Recombinants: Whenever there is creativity, more often than not it's in the form of what Gitlin calls "recombinants," combinations of successful formats from previous shows. For example, when the breakthrough hospital drama St. Elsewhere was in development, it was called "Hill Street in the Hospital;" i.e., it was understood as a combination of the gritty realism of Hill Street Blues with a conventional hospital format. (Sometimes this gets ridiculous: famous executive Fred Silverman once got NBC to make a made-for-TV movie called "The Harlem Globetrotters on Gilligan's Island.")

Conclusion

The moral of all this, again, is not that TV executives are unimaginative. The point is that television shows are the way they are to a large degree because of the structure of the system within which they are produced: a fairly centralized system funded almost entirely through the advertising of consumer products. In fact, creativity seems to increase when things are uncertain in the system. When the Fox network was new, it had almost no audience and was groping around for something different, and let an obscure comics artist called Matt Groening create a cartoon sitcom called The Simpsons. When the show proved successful, it prompted a rennaisance of prime-time cartoon shows. More recently, in the last several years, the structure of the television system has been made uncertain by the proliferation of cable channels and the internet, with a decline in ratings of big networks. People inside the system are thus uncertain about where things are headed, and they are therefore trying more new things than they usually do. Sometimes this leads to the unusually crass, like I Want to Marry a Millionaire, but it can also lead to some interesting experimentation, like The Sopranos.