Introduction: Making Sense of the Unknowable

The most common and basic form of human communication is face-to-face conversation. When a few people talk to each other, there is constant feedback: when one person holds the floor, the others constantly nod their heads, make small interjections ("yeah, that's for sure") and otherwise give the speaker feedback. People are so naturally hungry for feedback that, even when there's nothing to say, we feel compelled to fill the space with idle chit-chat and interaction -- that's what all those pointless comments about the weather are about. (If you want to test how much we need feedback, try this: next time a friend talks to you casually, try providing no feedback; do not react at all, don't nod your head, say nothing, and just stare. I promise that within 30-40 seconds both of you will be very uncomfortable.)

Perhaps the most distinctive thing about modern mass media are their lack of feedback. If you communicate to people by say, printing a million copies of a magazine and sending them out to the world, or by talking into a TV camera lens which sends signals out into the air, you are putting yourself in the unusual situation of communicating with basically no feedback from your audience. As human communication goes, this is very odd and difficult. The mass communicator is in the position of your friend when you just stare blankly and don't respond.

There is a great deal of talk in the media about the "audience," about the readers, listeners and viewers. But it is important to acknowledge from the outset that the "audience" is not a name for something that we know about; it's a name for something about which we lack information. The "audience" really is a word for a problem, the problem of no feedback. Todd Gitlin, in an article we read earlier, calls this "The Problem of Knowing," pp. 19-30. The audience is a riddle, not a description of a thing known, of an object out there. The audience is a name for a mystery, a mystery that we in modern society have made for ourselves.

Problems with the concept of the "masses" and "mass media"

There are a variety of ways of trying to solve the mystery of the audience. One of these are the interlinked concepts of "the masses" and "mass society" -- the concepts implied by the term "mass media" itself. In the 20th century there has been a scholarly tradition of thought called "mass society theory." Mass society theory speculated that in modern industrial societies, people are no longer differentiated by community or class or other social groupings; people are lumped together in "masses" which means they are a huge, undifferentiated group composed of anonymous, atomized individuals -- a gray, lonely crowd. People who work in the media sometimes use informal versions of this theory when they try to guess what their audience is like. They sometimes say things like "we need to reach Joe Six Pack," for example, by which they mean some working class guy, sprawled in his Lazy Boy after a day on the job, remote in one hand, a can of beer in the other.

But Joe Six Pack is a stereotype. If someone working in the media speaks of "Joe Six Pack," it's a pretty safe bet that he or she doesn't actually know many people fitting that description; if he or she did, they'd talk about actual people, not about a stereotype.

Raymond Williams once said, "There are no masses, only ways of seeing people as masses." Nobody ever says "I am part of the masses." The masses are a way of referring to people we do not know, a way to try to make sense of others in a modern society where we are connected abstractedly to thousands or millions of others that we can never really get to know face-to-face. Williams always insisted that "the masses," or related stereotypes like "Joe Six Pack," are an inadequate way to understand others. Real people, Williams argued, are unique individuals living in specific communities living rich, complicated lives. Speaking of folks as "masses" is condescending, a way of pretending we know more about people than we really do.

The Television Industry's View of the Audience: Sit Down and Be Counted

In an advertising-supported mass media, the predominant form of feedback is quantitative audience ratings. If you work for American commercial TV, you basically have to imagine the audience as a set of numbers. There are arguments about the accuracy of the ratings, but before you look at that, it helps to start by asking, "Why are there ratings in the first place?"

This might seem like a dumb question; how else, you might ask, are we to know who's watching? Well, there's a simple answer: you could ask them. You could hold a vote, for example. In Holland, for a long time that was how it was decided what would go on TV; every year, people would get to vote for various groups that advocated different kinds of programming, from sports to religion. Groups could put their programming on TV according to how many votes they got. No need for ratings measurement. (Another example closer to home is Mad Magazine. Mad does not gather circulation statistics, because it doesn't have to: it has no advertising.)

So why don't we hold a vote to see what people want to have on TV? The short answer is this: the language of money is numbers. Back in the 1920s, when it first became clear that our broadcasting system was going to be funded by advertising, a need arose to somehow reach arrangements between the now most important parties in the new business -- the broadcasters and the advertisers. A broadcaster couldn't just tell an advertiser, "a whole lot of people listen to my program; trust me." What was needed was some basis for bargaining over the dollar value of air time. The ratings numbers, therefore, could frame broadcasting in a language amenable to buying and selling. The ratings exist, therefore, primarily because of their value to industry members as a basis for bargaining and coordination among themselves. The accuracy and adequacy of the ratings, as far as the industry is concerned, is a secondary matter.

We'll look at how this logic plays out in the specifics of the ratings, but first it helps to notice that asking someone to express a point of view, as did the Dutch system, involves asking them to be active, to reflect on something and then take action. An advertising-oriented ratings sytem, by contrast, wants people to be passive: the CEO of the Nielsen Media Research company that dominates audience measurement in the US and many other countries once described "totally passive measurement" as the "Holy Grail" of the ratings industry. "Totally passive" measurement means people do not think or take any action at all; their viewing habits are just automatically transmitted to the broadcasters without them even knowing about it.

|

This is the "portable people meter," a beeper-like device being developed by Arbitron. It logs programming seen or heard anytime, anywhere by whomever is wearing it. The gadget requires nothing of participants other than to wear it during the day and place it in a home docking station each night so data can be collected and transmitted to Arbitron. The device uses sensitive microphones to pick up codes embedded in television, radio and even streaming Internet broadcasts - and it includes a motion detector to verify someone is actually wearing it." |

|

The Accuracy Controversy

Nobody says the ratings are totally worthless, but nobody says they're the most accurate thing in the world, either. Like all statistics, the ratings are just an educated guess, and they are an educated guess by for-profit companies; Nielsen Media Research, Inc. and Arbitron -- the two major ratings providers -- are not going to spend a penny more on ratings accuracy than they need to to sell their goods.

So the controversy lies in deciding how GOOD a guess the ratings are, particularly -- are they good enough to base major programming decisions on?

How broadcast ratings work

In the U.S., there are seven or so big national television networks, hundreds of cable networks, thousands of local TV stations, and more than ten thousand local radio stations. Ratings are available for all of these, but as one might expect in a marketplace environment, the smaller the market, the less money advertisers and stations have to pay for ratings services, and therefore the less precise are the ratings statististics. This means, then, that broadly speaking, the ratings are most accurate on a national level, somewhat less accurate in big cities, even less accurate in smaller cities, and not very accurate at all in small rural markets. The same kind of accuracy variation happens as audiences for particular programs get smaller. So we have a pretty good idea of how many people watched the last episode of Friends across the US, but a less clear sense of how many people watched the program in Burlington, Vermont. And we don't have much of a clue of how many people watched the History Channel at three in the morning last week in Fargo North Dakota.

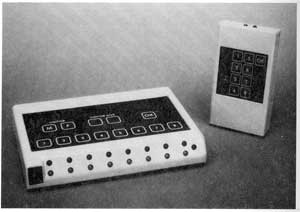

The Nielsen Media Research company has a practical monopoly of the nationwide market for ratings. They provide a variety of services to their clients, but they generally base their measurements on things they call "people meters." Each people meter consists of a box on top of the TV set and a handheld device. Everyone in a Nielsen "household" is assigned a number, and they're supposed to punch in that number in the handheld device everytime they sit down in front of the TV. The set-top box then records what channel is on and (hopefully) who is watching it; once a day the box dials into the company and uploads the data, which is then assembled into the ratings. (There's no way of knowing for sure how many people do not punch their numbers in when they're watching. Nielsen acknowledges this is a problem for them. As far as they're concerned, punching in your number requires too much activity of the audience -- hence their search for "totally passive" measurement where people do not have to do anything.)

Figure 2 Nielsen People Meter (ca 1989)

Sweeps Weeks: In smaller markets like Burlington, however, installing meters in people's homes is judged too expensive. For this reason, four times a year there are "sweeps weeks," periods during which Nielsen (and also its competitor, Arbitron) pass out paper "diaries" to samples of people in local markets. Participants are expected to voluntarily record what they watched for a few weeks and then mail it back to the company, which compiles the data. You can look at Nielsen's explanation of all this.

How accurate is all this?

As of this writing, there are 5,000 households in Nielsen's national People Meter sample, approximately 20,000 households in the local metered market samples (which just measure what is watched, but not who is watching), and nearly 1.6 million paper diaries are edited each year. Technically, that means, for example, that one Nielsen household in the national sample stands for about 54000 people in the US population. Some people worry that the samples are too small, that if, say, somebody's cat is watching the Nature Channel for an hour, Nielsen assumes that 54000 people were watching.

Nonrepresentative Sample Problems: Sample size, however, is really not the main complaint; statistically if the sample is a representative one, if it really represents a cross-section of the American population, then the sample size should be good enough. A much more incisive criticism is that the samples are not representative. In particular, there is a lot of concern that they don't represent the poor, minorities, old people, or non-family situations (e.g., students). As of this writing, in fact, Nielsen is currently under fire for underrepresenting minorities: see e.g., Richard Linnett, "Nielsen 'People Meter' Rollout Stalls On Controversy: NYC Politicians, Networks Fear Undercounting of Minorities," Advertising Age, April 07, 2004 . There are several structural reasons for this. First, it is harder to find and install meters in reliable homes among poor, non-English speaking, or highly transient populations. Second, advertisers are mostly interested in people with considerable amounts of money to spend, and thus are not going to want to pay the extra cost of ratings that measure not-very-wealthy audience segments. Nielsen thus does what it can within these limits.

Do people watch the ads?: Another problem that is of more concern to the industry involves people using technology to essentially gain more control over what they watch; as the audience gets ever-more "mobile" in front of the screen, it gets harder to measure. The process began with the arrival of remote controls, VCRs, and cable TV around 1980: audience members began creating headaches for Nielsen and the advertisers by channel-surfing, taping programs, fast-forwarding through commercials, and distributing themselves over an ever-growing number of channels. The Nielsen company has tried to keep up with the audience as it scampers off in all kinds of technological directions: their national sample now measures every device in the house, not just the living room TV set, for example. But as the options grow, the audience gets harder to measure. "Digital video recorders" like the Tivo (DVRs, or PVRs for "Personal Video Recorders") currently have the industry in something of a panic because they give audience members a variety of ways to skip commercials and otherwise confuse the ratings. The audience, apparently, does not always want to just "sit down and be counted."

The Sociology of Ratings Accuracy

It sometimes seems like the media industry is in a mad and desparate struggle to measure the audience as accurately as they can. But this needs to be looked at in context. There are sometimes cases where accuracy seems like the last thing on the industry's mind. During sweeps weeks, for example, TV networks run blockbuster programming -- things like having big stars make appearances on sitcoms or running big Hollywood movies in prime time -- in order to inflate the ratings. This practice totally throws off the accuracy of measurement because the ratings are used to determine the value of advertising time in non-sweeps periods, when there is no blockbuster programming. But the practice of sweeps weeks programming is almost thirty years old now, and people in the industry tend to just shrug it off. Also, as the audience has become more thinly spread across the hundreds of channels now available, the degree of measurement error has gone up, but decisions about whether or not to cancel a series and how much to pay for advertising treat the ratings numbers as if they were extremely precise. Some academic statisticians argue that advertisers and broadcasters are frequently just buying and selling measurement error to each other. But they don't seem to care.

One ABC executive once explained this phenomenon this way: "you can't really take into consideration everyday, 'boy do I have confidence in that number or not?' . . . It wouldn't really be practical to think about whether these numbers are right or not." Similarly, an advertising agency executive noted, "The Nielsen ratings right now represent an agreement between the buyers and sellers to use them as the currency of negotiation. . . . for what we're doing with the ratings and the way we plan, buy, and execute, it works just fine." In Gitlin's words, "Once managers agree to accept a measure, they act as if it is precise. They 'know' there are standard errors -- but what a nuisance it would be to act on that knowledge. And so the number system has an impetus of its own."

This is where one needs to remember the force of what Gitlin called the "television-industrial-complex." The industry concern is first of all that they have numbers on which to base the value of advertising time; without those numbers they can not do business. The system as a whole is the main thing that pays people's salaries, and therefore maintaining the system is more important than precisely adopting to the complicated needs, interests, and wants of the audience. No media system can perfectly solve the riddle of the audience, but different systems will address it differently, with different results.